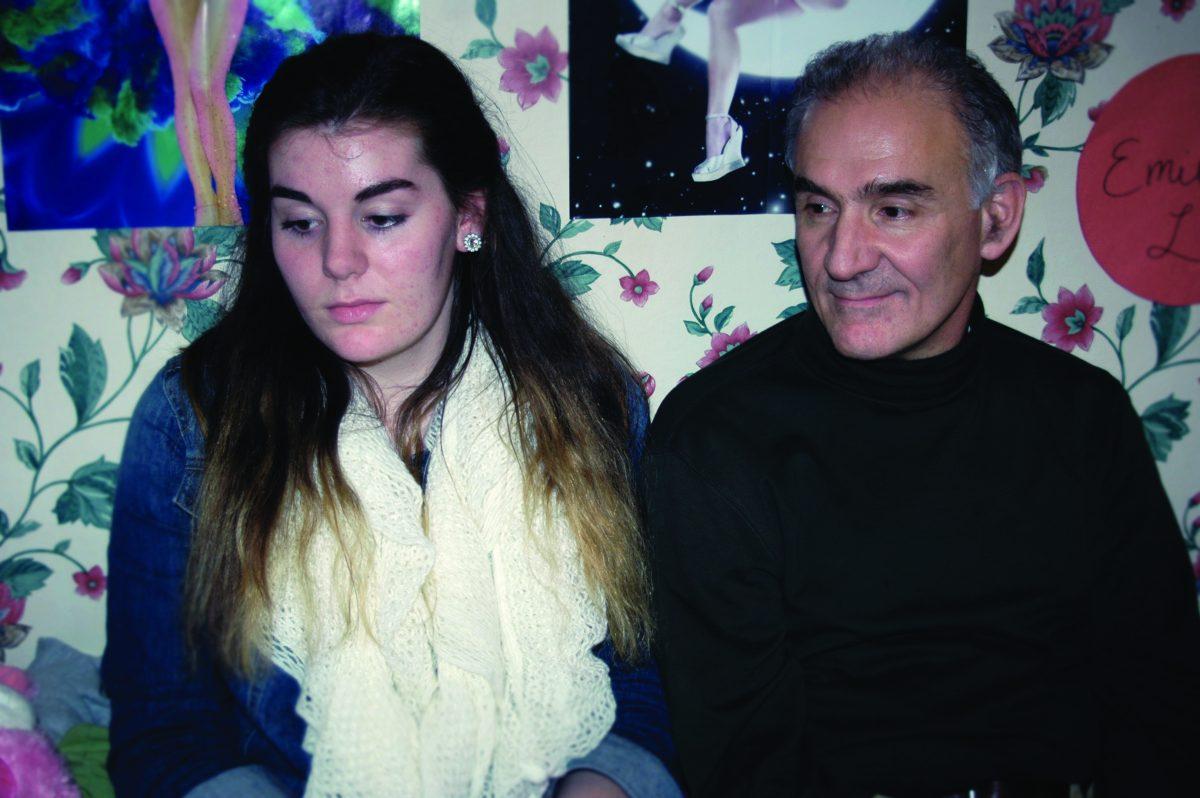

Tears ran down Emily Locke’s face. Streaks of makeup left black stripes on her cheeks. Her then-boyfriend was in a hospital in Milwaukie and undergoing surgery. She was driving there to see him and was alone with her thoughts. She felt hopeless. Her first encounter in treatment didn’t help her with her eating disorder and she had relapsed. She had hit a wall of depression and wanted to end things.

“A few weeks had gone by and I was hanging on by a thread, and then I snapped,” Locke, now a Grant junior, recalls. “I tried so hard and there was no reason to keep trying.”

She shut her eyes and slammed on the gas. She lost control of the car and missed a telephone pole by a couple feet. Sitting on the curb crying, Locke was relieved that she didn’t die. In fact, she saw it as a second shot at life.

Locke, who was a sophomore at the time, had been diagnosed with anorexia nervosa purging disorder. It’s an affliction that differs from typical anorexia because those with this disease have a normal body shape. They also don’t consume a large amount of food before purging. She attended outpatient treatment for eight weeks but it didn’t work. “I was only doing it to please my parents,” says Locke.

She remembers the first time going in for counseling and seeing life-sized body posters with encouraging words filling the walls of the treatment center. But the distractions couldn’t take away from the reality – the bony faces and bodies of girls who were suffering like her, their frames hidden beneath sweatshirts and sweatpants. Many were victims of a type of self-destruction that girls face now more than ever. They needed help.

“We were all there for eating disorders, but I felt that didn’t matter,” Locke remembers thinking, largely because she wasn’t as skeletal looking as the others. “My problem must not be as serious as theirs because of how I look and having not been hospitalized.”

It wasn’t until her near-car wreck that Locke made the first real step toward recovery. That’s when she checked into a residential treatment center in Edmonds, Wash.

Locke isn’t alone. Girls around the world face pressure to maintain an ideal body image. Young females are constantly given attention about their appearances and are conditioned to look “perfect.” It’s unavoidable. Drive down any major street and you’ll find billboards featuring pictures of flawless, sexy women staring down at passersby. People at grocery stores wait in checkout lines and flip through magazines that feature the “perfect image” of women, something that carries over to school.

Grant vice principal Kristyn Westphal notices the way girls dress at school. She sees the low-cut shirts and tight skirts girls wear, and sees the distractions such clothes cause. But she also knows girls feel pressure about their appearances. “It’s a significantly more rampant issue at Grant than at any other school I’ve spent time in,” Westphal says. “I think skimpy dressing is all about attention-seeking.”

And that’s just what it is. Experts say girls often feel the need to seek approval by distracting others with provocative styles in order to conceal what they feel self conscious about.

Annie Robertson, a Portland psychologist who works at a mental health center with adolescents who have eating disorders, says the media’s portrayal of women can create problems. “The fashion industry profits off of women’s insecurities,” she says.

Annie Robertson, a Portland psychologist who works at a mental health center with adolescents who have eating disorders, says the media’s portrayal of women can create problems. “The fashion industry profits off of women’s insecurities,” she says.

Robertson says the standards set by images in mass media are hard for women and girls to reach. But by having a society so obsessed with looks, she says teens feel a sense of failure because they aren’t able to achieve the ideals society appears to value.

The billboards, magazine covers and other depictions of women add up. It’s virtually impossible to go anywhere without seeing an electronically altered face or waist. Editors take off pounds and blemishes in seconds using computer software. They add to bra sizes, make lips bigger and legs leaner all with a couple clicks of a computer mouse.

Such artistry is impossible to do in person, so girls at Grant and other high schools use clothes and makeup as the easy alternatives to hiding blemishes and other flaws. For some girls, it provides a level of confidence if they can leave the house in the morning feeling beautiful. Some put on makeup subtly, while others go overboard.

Senior Bret Pinkley says: “I look for girls who don’t mask their appearance with an overdose of makeup. None is better than too much.”

In the hallways, some girls judge their peers based on how they look. It’s not uncommon to hear: “What is that girl wearing?” “She looks like a slut today.” “Ew, she looks fat in that outfit.”

In an environment consisting of teens struggling to discover their identities, harsh words can have a lasting effect. School – a place that should be safe and comfortable – isn’t anymore for students, some say.

Fred Locke, Emily Locke’s father, knows the arena well. He’s the principal at Portland’s daVinci Arts Middle School. “School should solely about school and nothing else,” he says.

Robertson says it boils down to the way girls see themselves. She estimates that girls she councils spend up to 70 percent of their time thinking about how they look and the type of body shape they have.

Whether it’s at school or in the real world, young women have always been objectified. In the 1960s, Twiggy – then a teen fashion model, actress and singer – became the poster child for the new thin look. The fashion runways quickly became dominated by an androgynous look, transforming the once voluptuous figures of women into the modern, lean look we still see today.

Emily Locke’s mother, Holly Locke, majored in women’s studies at Portland State University and today holds a job at Friends of the Children, a non-profit organization. She remembers issues about how women looked began to change after women gained power in the 1960s from the feminist movement. “When women started gaining power, their body sizes starting getting smaller,” she recalls. “American culture, dominated by men, has pushed women into a corner of physical weakness to balance out the advancements they’ve made in the workplace.”

Although girls are pressured to believe skinny is the only socially acceptable appearance, some teenage boys at Grant say that while they appreciate an athletically fit girl, curves are a plus. Junior Kyle Rochez says he finds it degrading to judge girls based on their bodies. When asked about the ideal body shape, Rochez says:

“Skinny is unattractive. Don’t try to be what some loser Photoshop wants you to be.” Nate Golden, also a junior, says “skinny is not the only socially acceptable appearance. Just the expected one.”

Girls at Grant are reluctant to believe what these boys say. Freshman Reagan Mims laughs when she hears guys say they don’t have a preference on size.

Along with the skepticism comes confusion as girls wonder whether boys will tell the truth. “I know most boys respect girls and view them as friends and equals, but when a boy thinks a girl is hot, he views her as an object,” junior Julia Sherman says.

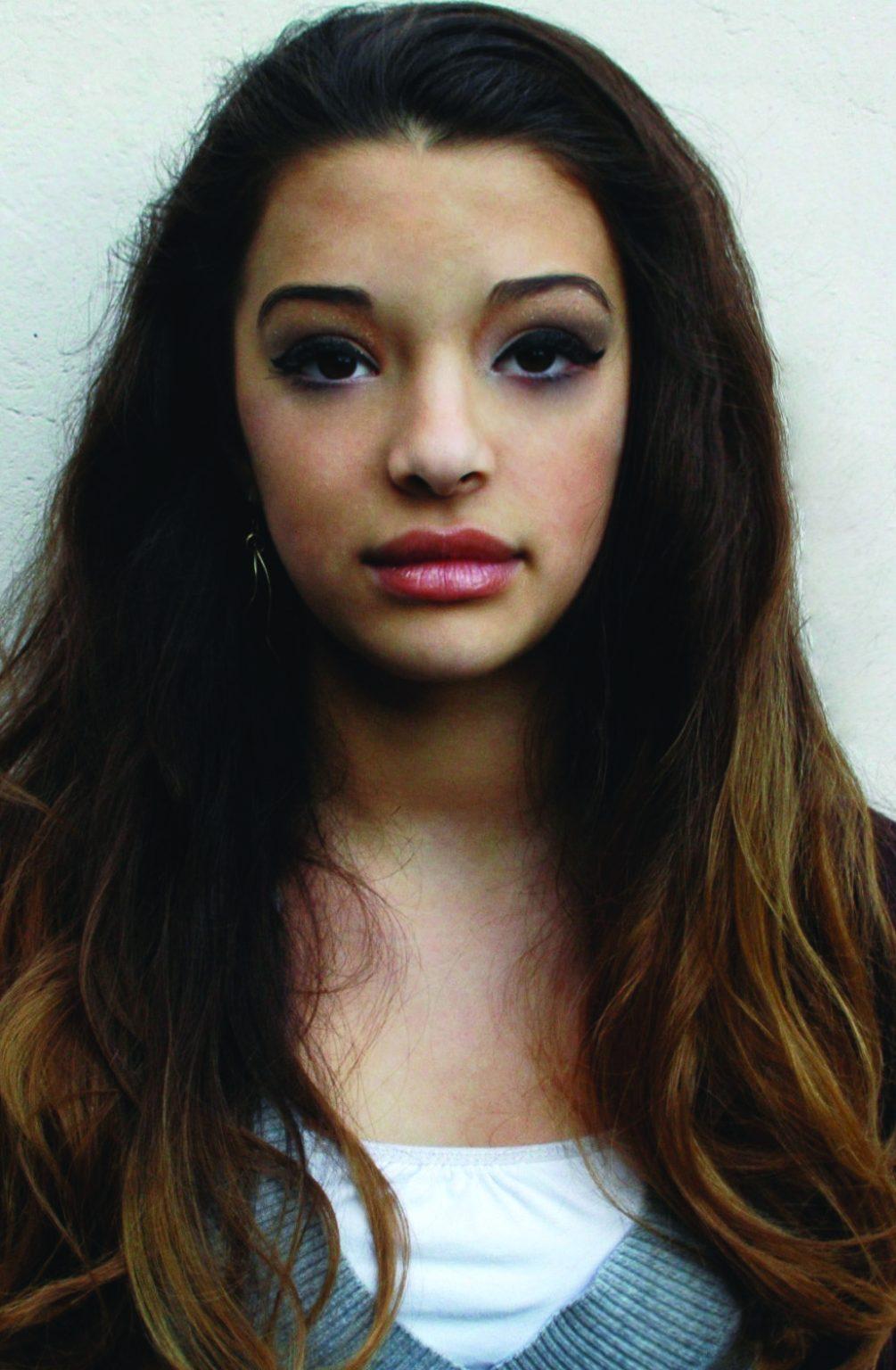

Grant freshman Jaida King models for Option Model Management and remembers when her agents told her to lose 10 pounds. Already thin, tears filled her eyes when her mom broke the news to her in the car. “My mom was always very supportive, though,” King says.

Her mother wanted her to lose the weight safely, so she bought healthier foods and stopped buying junk food. King also began playing soccer, which helped her lose the weight while maintaining a normal, healthy lifestyle.

Muse model and Grant senior Chelsea Unsworth also faced a weight-loss dilemma. In order to be successfully promoted in New York for international modeling, Unsworth was told she needed to lose an inch off her waist. She weighed 120 pounds, but casting agents required her to get even thinner.

Her mother opposed the idea because she didn’t want her daughter losing excessive weight on demand. “You cannot take anything they say personally,” Unsworth says. “It’s hard to hear them say that they want you to have less of a womanly figure. They told me to lose weight off my butt.”

Her mother opposed the idea because she didn’t want her daughter losing excessive weight on demand. “You cannot take anything they say personally,” Unsworth says. “It’s hard to hear them say that they want you to have less of a womanly figure. They told me to lose weight off my butt.”

Locke remembers feeling pressure from her father, a former Oregon Ballet Theater teacher and professional dancer. He had high expectations for his daughter, but she saw it as a push by her dad for her to achieve the “ballerina body.”

“He would say how if I ever wanted to achieve my dreams for dance that I needed to have a perfectly flat body with ‘no imperfections,’” Locke recalls. “And at meals, he would say ‘Are you sure you wanna eat that bread? Are you sure you wanna eat that much?’ He would be even worse if from time to time I wanted something like a cookie or a milkshake.”

Although their relationship back then hit rock bottom, it since has become a lot stronger. “In the long run, it was an amazing learning experience for Emily, as well as our family,” Fred Locke says. “The communication is better now.”

Her father says he was only trying to look out for her, but if given the chance to take back what he said, he would. “What I can do now is do my best to support her,” he says.

Emily Locke says she’s gained self worth and now has a new outlook. “I’m not constantly thinking I have to look like that,” she says. “I don’t think I’m perfect, but I accept it.”

A message she wants other girls to hear is that women don’t have to be a certain type to be beautiful. “Love and take control of yourself,” Locke says. “Girls need to fight for themselves in every way they can.”