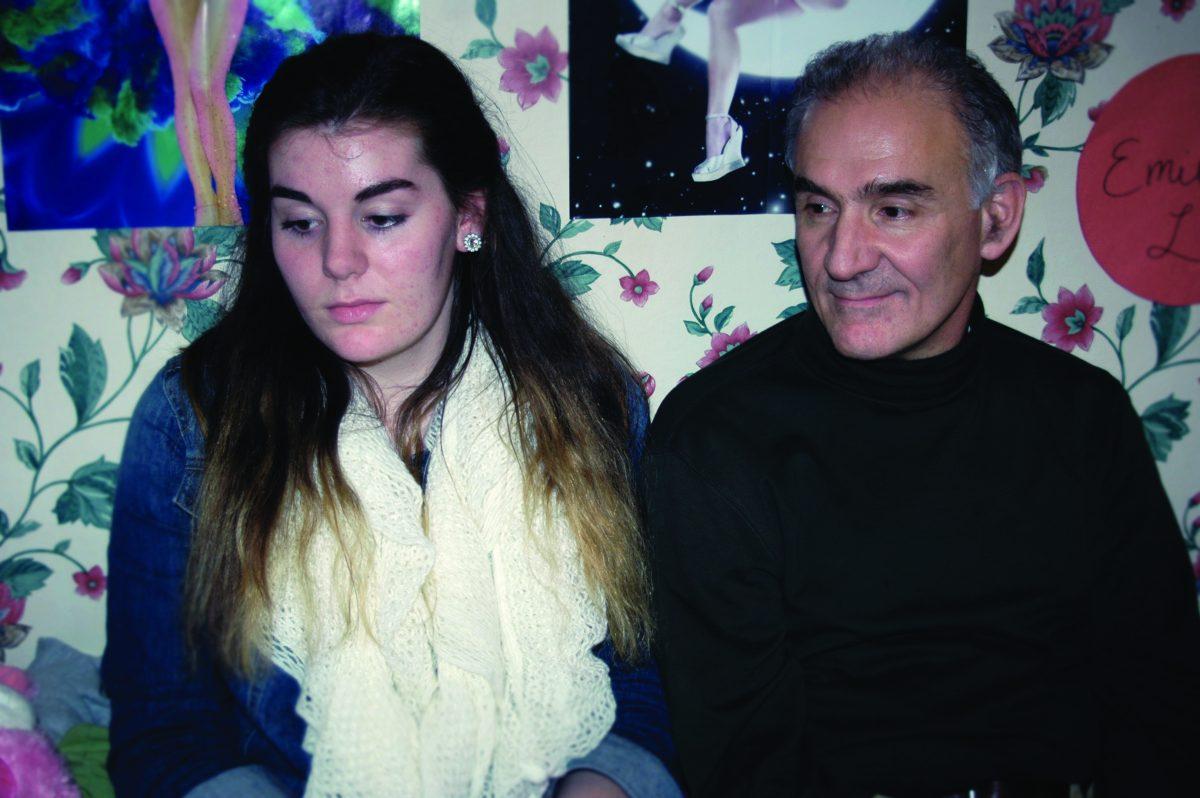

Last month, Grant High school senior Ruth Strauss walked into the Panera Cares Café in the Hollywood district during lunch hour and approached the counter. Her stomach growled as she scanned the menu board.

A woman behind the counter stepped forward and asked her if she went to Grant. When she responded with a “yes,” the woman politely asked her to leave.

“As a customer who always put in a good amount, it was such a surprise that I almost couldn’t believe it,” Strauss says. “I don’t think it’s fair, and I liked their food so it’s a shame. I feel like they don’t deserve my business anymore.”

Panera is a non-profit community café that allows customers to pay what they can. The community care café system was set up by founder Ron Shaich three years ago to bring attention to food insecurity problems in the United States.

Shaich, who is based in the Boston area, hoped to start a café where customers could pay what they could afford. Shaich thought if people pay more, the money could go to someone who can’t afford a meal. It creates community, Shaich says.

The statement on the Panera care website sums it up: “Panera Cares community cafés exist to feed each and every person who walks through our doors with dignity, regardless of their means.”

When Panera opened the Hollywood location in 2011, things went according to plan. Panera had opened and converted stores successfully before in 2010 in Missouri and Michigan. Getting started, it takes some training of communities to ensure they understand the Panera mission. “All of our cafes see the same response the first couple of weeks,” says Kate Antonacci, the manager of the national chain. “At the beginning, people give a high donation, and then it goes down to an amount that we’re uncomfortable with and then it levels out.”

But in Portland, a surge of Grant students started flocking there at lunch. Word had gotten out there was an opportunity to enjoy a sandwich or baked good for next to nothing. Most students misinterpreted “pay what you can” to mean “pay what you want.” Café staff worked to explain the philosophy, going as far as contacting the school and administrators for guidance. Despite these actions, Grant students continued to abuse the system.

Over the past year, Panera officials began to notice a problem regarding the student practices of leaving little or no money. The Panera staff and administration realized many Grant students were unwilling to learn about Panera’s mission and concept. After approaching the Grant staff, Panera realized they needed to limit the hours that students would be allowed into the café.

Over the past year, Panera officials began to notice a problem regarding the student practices of leaving little or no money. The Panera staff and administration realized many Grant students were unwilling to learn about Panera’s mission and concept. After approaching the Grant staff, Panera realized they needed to limit the hours that students would be allowed into the café.

“The decision was made on a recommendation from the administration at Grant High School,” says Antonacci.

Grant administrators recognized there was a problem and that some students were giving the school a bad reputation in the community. Vice Principal Curtis Wilson says he understood Panera’s position.

“When they called the school several times last year with concerns about students utilizing their services without leaving a proper donation, my advice to them was to cut students off from buying delicious sandwiches for a dollar or nothing,” Wilson said.

Eventually the decision to ban Grant students came down to how so many were treating the system poorly. “Many thought that it was acceptable to come in for a meal regularly and leave little or no money for that meal,” Antonacci says. “That is not how Panera Cares works. We are about a hand up, but not a hand out. We exist to help those struggling with food insecurity.”

Having this kind of café in a community is beneficial, says Israel Bayer, editor of Street Roots, a Portland newspaper that focuses on homeless issues. He says Hollywood is an ideal neighborhood and community due to its blend of poor, middle class and wealthy families.

Overall, roughly 60 percent of the customers leave the suggested amount, about 20 percent pay less or nothing and the remaining 20 percent pay more, Panera representatives say.

Grant students are not the only problem the café has struggled with. Staff say they have experienced a similar situation with Portland’s growing homeless population. Rumors get spread about free food and a place to hang out all day. The ambassadors end up having to tell some of the homeless to leave.

Bayer sees Panera as a community treasure, despite the issues. “I think that establishments like Panera and Street Roots have to deal with situations using a case by case scenario,” he says. “At Street Roots, there have been times when someone with a mental health or addiction problem has been asked to leave and come back when they’re more put together.”

“The problem with many soup kitchens is that the only people around them are also poor,” he added. “Food insecure people at Panera feel more integrated and part of society.”

Bayer says bringing a high school into the mix can be difficult, due to the fact that Panera Cares is an experiment.

While some students at the school might actually need the financial help Panera offers, it’s difficult to tell which individuals are in a tight economic spot. Does this go against Panera’s mission? Antonacci says no.

“We need to create a fine balance,” she says. “We can’t feed people who are unwilling to understand our role in the community and think our organization is a joke. That’s what some Grant students were doing and that’s why we can’t do business with them anymore.”

Panera officials asked Grant administrators to develop a policy for students who wanted to go to the café. They also asked the school to host an informational assembly and help monitor students who went there.

Panera officials asked Grant administrators to develop a policy for students who wanted to go to the café. They also asked the school to host an informational assembly and help monitor students who went there.

While vice principal Wilson sympathizes with Panera, he said Grant doesn’t have the resources or time to monitor where students go at lunch. He didn’t know Panera stopped letting Grant students in. “I wasn’t aware that they actually made the official change,” says Wilson.

Georgia Wagner is the general manager at the Portland location. She says Panera sees a number of elderly people, young families and others who are running out of food stamps at the end of the month come through the doors. This is one of the reasons that Grant students get pushed away.

Panera managers say they understand some Grant students may actually want to give the correct donation or even more. But they feel if they begin to omit some students from the rules, then everyone will want exceptions to be made for them.

“To remain consistent, even if a student comes in with a hundred dollars we can’t serve them,” says Antonacci.

Like Wilson says about Grant, Wagner says the same about Panera staff. “We currently don’t have time to go out and educate our community,” she says. “We need to find our solutions within our cafes and educate people within our walls.”

Not letting in a certain set of people makes students like Strauss mad. “Before, it seemed like something that helped the community,” she says. “Panera doesn’t know everyone’s story who goes to Grant, some students might need the help.”

But while the solution to the Grant student problem has been to shut them out, it’s not seen as permanent.

“We plan to continually re-evaluate our relationship with Grant High School. We will continue to meet with administrators and are more than open to meeting with students. There could certainly come a time down the road when this rule is amended,” says Antonacci.

Students who spend time volunteering tend to believe the program plays a special role in the community where for-profit restaurants make up most of the places to dine out.

Miriam Kohn, a Grant senior and active member in the school’s national honor society, says Panera made the right choice. “I think it’s a totally valid business decision. Panera was taken advantage of on a consistent basis. Unfortunately, the only sure way to prevent this is to shut out Grant students.” ♥