Colton – Angie Payne fights to hold down the feet of one of the turkeys on her nearly nine-acre farm. Her son-in-law, Jesse Gordon, slits the bird’s throat and pierces its brain. It is dead within seconds, but continues to flap with built-up muscular energy.

Once the turkey stops moving, Payne starts the preparation for dinner. “This is my other job. It’s fun,” says Payne matter-of-factly, tossing the bird’s severed feet to Horus Hogbottom, a 250-pound Tamworth pig lying half submerged in cold mud nearby.

Afterwards, Payne cleans up and heads inside. Her grandchildren are in the kitchen, helping their mom make batter for German pancakes. Zeke, who is just over a year old, laughs with delight when Payne comes in.

When she isn’t working on the farm or taking care of her family, Payne can be found in the main office of Grant High School, working hard to keep the place running.

“She’s the heart of the school,” says English teacher Mary Rodeback, later changing “heart” to “furnace” after thinking about it. It’s hard to say if either word truly captures Payne’s crucial role at the school.

Aside from organizing Principal Vivian Orlen’s schedule, Payne’s job includes managing the school calendar, handling teacher attendance, arranging substitutes, overseeing payroll, and taking calls from just about anyone who tries to contact – and sometimes yell at – administrators.

Payne gets the job done with unfaltering vigor. “She is an incredibly hard worker,” says Orlen.

Payne grew up as Angie Gettman in a modest Northeast Portland house on 85th Avenue and Fremont Street. She was the youngest of four children. Although her home life was nice, her favorite memories come from summers spent on a two-bedroom houseboat on Lake River in Washington State. The family of six stayed there every year, and the limited space kept them very close. “We were very family oriented,” she says.

Payne grew up as Angie Gettman in a modest Northeast Portland house on 85th Avenue and Fremont Street. She was the youngest of four children. Although her home life was nice, her favorite memories come from summers spent on a two-bedroom houseboat on Lake River in Washington State. The family of six stayed there every year, and the limited space kept them very close. “We were very family oriented,” she says.

She smiles as she recalls “sun up to sun down salmon fishing” with her older brother. They would get up before dawn and take the family fishing boat out on the river. “I can’t even remember not fishing,” she says.

Waterskiing was also an integral part of her childhood. The kids would take turns skiing up and down the river on warm summer afternoons, falling in often.

One time, she remembers, her father was doing construction on the houseboat and their 17-year-old cocker spaniel fell into the river. The dog was both blind and deaf. Her dad jumped in after him, heroically pulling the dog from under the house.

Payne attended Gregory Heights School from kindergarten to eighth grade, and later attended Madison High School. At Madison, she wasn’t into sports, preferring to spend her time at home or in the business department at school. “I wasn’t a kid who just clicked in school,” she says. “I was there to get it done and get out. I always knew I wanted to be a secretary, and that was my goal.”

After she graduated, she landed a job as a secretary at U.S. Bank. Later, she found a similar position at an appliance distributing company. She purchased a freezer in December 1978. On a less than spectacular morning, Paul Payne delivered it.

Three months after they met, Paul and Angie got married.

“That just was it,” Angie Payne recalls. There was no drama. They just clicked.

“We didn’t do a big wedding,” she says. No white dress. No walking down the aisle. Only family was invited. It was “a Vegas wedding in Portland,” says Payne.

They had three children: Stacie, Stephen and Tim. All three attended Rigler Elementary, and Payne often volunteered there in classrooms and the office. People took notice of Payne’s hard working spirit, and she was offered a secretarial position at Grout Elementary in Southeast Portland.

“I was a mom who volunteered in my kids’ school and ended up with a job,” she says. It was the beginning of a 20-year career with Portland Public Schools.

In December 1984, when Payne was pregnant with her youngest,

In December 1984, when Payne was pregnant with her youngest,

their small, two-story bungalow caught fire. Half the house was burned to the ground. But that didn’t stop the Payne family. They rebuilt it practically on their own, finishing just before Christmas Eve. By that time, there weren’t any Christmas trees left to buy, so they improvised. “We put lights on a houseplant and called that our tree,” Payne recalls. And she still has the Umbrella Tree to this day.

When Stacie, the oldest, was 12, the Payne family moved to Oregon City. They wanted a quieter, more comfortable environment for the family. They lived there until the kids were almost out of high school and moved to the Colton farm in 2000. Angie Payne hadn’t even seen the place before they bought it, and there was serious work to be done.

They re-floored the entire house, rebuilt the barn, added several outbuildings and logged a few trees. That was around the time Payne started her job at Grant.

The high school was huge compared to other schools where Payne had worked and the retiring head secretary couldn’t do much to ease the transition. “The one thing she did do was give me a yearbook and advised me to ‘get to know people,’” says Payne.

Today, it’s easy to see Payne’s home life in her work at Grant, and her maternalistic nature shines when she’s on the job.

One of her closest friends at Grant is English teacher Therese Cooper. Like many others, she sees Payne as a motherly figure. “She takes care of us,” says Cooper.

“She’s nice, but she can also be strict,” says Deja Willingham, a student assistant in the main office. Willingham sees firsthand how hectic it can get in the main office.

On a recent school day, Payne handles an issue with a load of outgoing mail. She abruptly calls athletic director Diallo Lewis back into her office as he walks out the door. They hash out a meeting date and she jots it down on an 18-by-24 inch calendar near her desk.

Business teacher Anne Berten drops off a bulky paper package as Payne greets two nurse interns passing through the office. After a quick call from Leah Kirschner, Payne sends a custodian to fix a leaking heater upstairs. Then she’s off again, darting back and forth from her desk to the office printer.

Just as she sits down and opens up a thick white binder, Allen Carpenter, a PPS IT project manager, walks in. He seats himself at Payne’s desk and pulls out his iPhone. After pressing play, Carpenter holds out the phone to show Payne a video of his grandson singing the alphabet song.

Payne counters with a picture of her two-month-old granddaughter, igniting a string of stories and a tongue-in-cheek argument. “You’re just jealous ‘cause I have more grandkids than you,” Payne says playfully as Carpenter stands up to leave.

He doesn’t hesitate to respond. “Mine are cuter,” he teases.

The entire office gasps in mock disbelief, only to be broken by laughter a few seconds later. Then Payne is back to work. Her job, she says, is sometimes like her home life. “They are similar in many ways,” she says. “Wrangle goats, wrangle staff. You get my idea.”

At the end of the day, it takes her more than an hour to get home. But Payne says the long commute is worth it. Every day, she arrives home to the small farm where she lives with her husband, daughter and son-in-law, and her three grandchildren.

Mud puddles and a swinging metal gate guard the front of the property, only a few yards from a quiet highway southeast of Portland. Once you make it in, a vivacious Aussie-Border Collie named Suzie literally knocks you off your feet. Huge pigs roll over in the mud to the right. Goats and turkeys stare from the left.

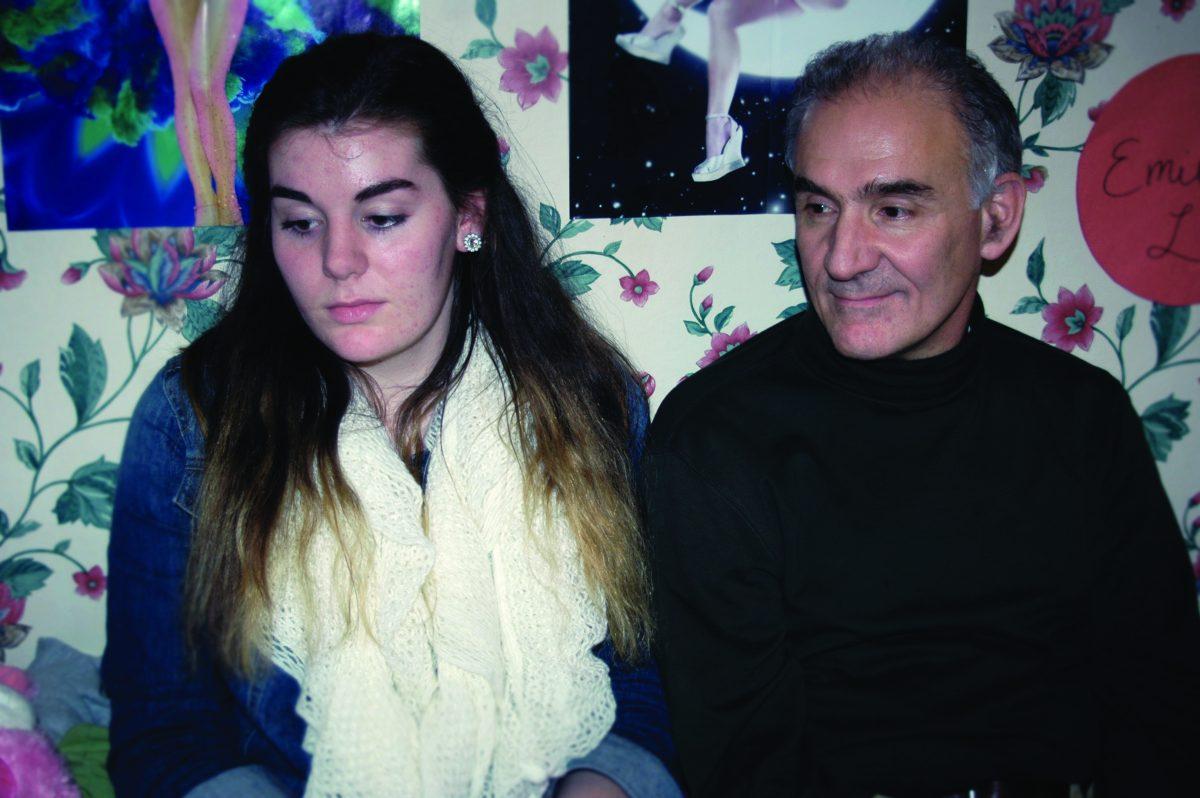

When Payne walks in the door of her home, she is greeted by her self-pronounced life motivation: her grandchildren, 7-year-old Joey, 5-year-old Faith, and the baby Zeke. The kids’ parents, Stacie and Jesse Gordon, are also there waiting.

The latter two generations of the family moved onto the farm about four years ago. “We’ve always been really close with my parents, but we didn’t get to spend much time together,” says 32-year-old Stacie as she mixes the batter for German pancakes, using fresh ingredients from right outside.

Family time isn’t hard to come by anymore, because they all live under the same roof, sharing in the perks of multi-generational living.

“What better way to live out your older life, but by being around young kids?” says Payne as she watches her grandchildren run around outside pretending to be Walt Disney characters.

With the new family members on the property came even more farm animals. Today, the Payne family has more than 50 animals on the farm. But that number changes with the seasons. Currently, they have rabbits, pigs, geese, turkeys, and chickens – including a rooster given to the Payne family by Grant art teacher Jamin London-Tinsel.

With the new family members on the property came even more farm animals. Today, the Payne family has more than 50 animals on the farm. But that number changes with the seasons. Currently, they have rabbits, pigs, geese, turkeys, and chickens – including a rooster given to the Payne family by Grant art teacher Jamin London-Tinsel.

They also have goats, which are Payne’s specialty. She nursed one Angora goat named Ariel (yes, as in the Little Mermaid) back to health after the animal fell terribly ill last summer. Ariel’s reddish brown coat will be sheered, spun, and knitted into clothing by Payne when her wool is ready next spring.

Chicken, goat’s milk, and goose eggs are consumed frequently at the Payne house, and they have a copious perennial garden where a good portion of their fruits and vegetables are grown. “If we can grow it, we do,” says Payne.

Stacie Gordon is the one in charge of the garden. Her mastery is evident when she walks through the many raised beds, explaining how to prune a strawberry bush, and how the Borage herb makes fantastic hot tea.

Four large meat freezers rest on the front porch. Mason jars of canned peaches sit on the kitchen shelf. Nearly all the food consumed at the Payne house was produced there, with the blood, sweat and tears of every member of the family.

Everyone puts in their fair share of work on the farm to keep it running smoothly. This time of year, that means helping prepare turkeys for dinnertime.

Payne’s roll-up-the-sleeves work ethic is incredibly valuable at Grant, especially to Orlen.

When the new principal first arrived at Grant, tensions were high. Orlen’s new ideas tested the traditional office dynamic. Payne was cautious. During the summer of 2010, Orlen set out to change the way the main office operated. “She wanted to be available,” says Payne. She had walls torn down and windows installed, visually opening the office. Payne helped facilitate the project, and the two bonded over it.

Payne adapted well to the changes, according to Orlen. “What I think is really special about Angie is her willingness and enthusiasm to do her job differently. I really appreciate it,” she says.

Orlen has incredible respect for Payne, and even looks up to her. “I often want Angie’s approval, which is kind of funny,” she says. “But there’s something about Angie.”