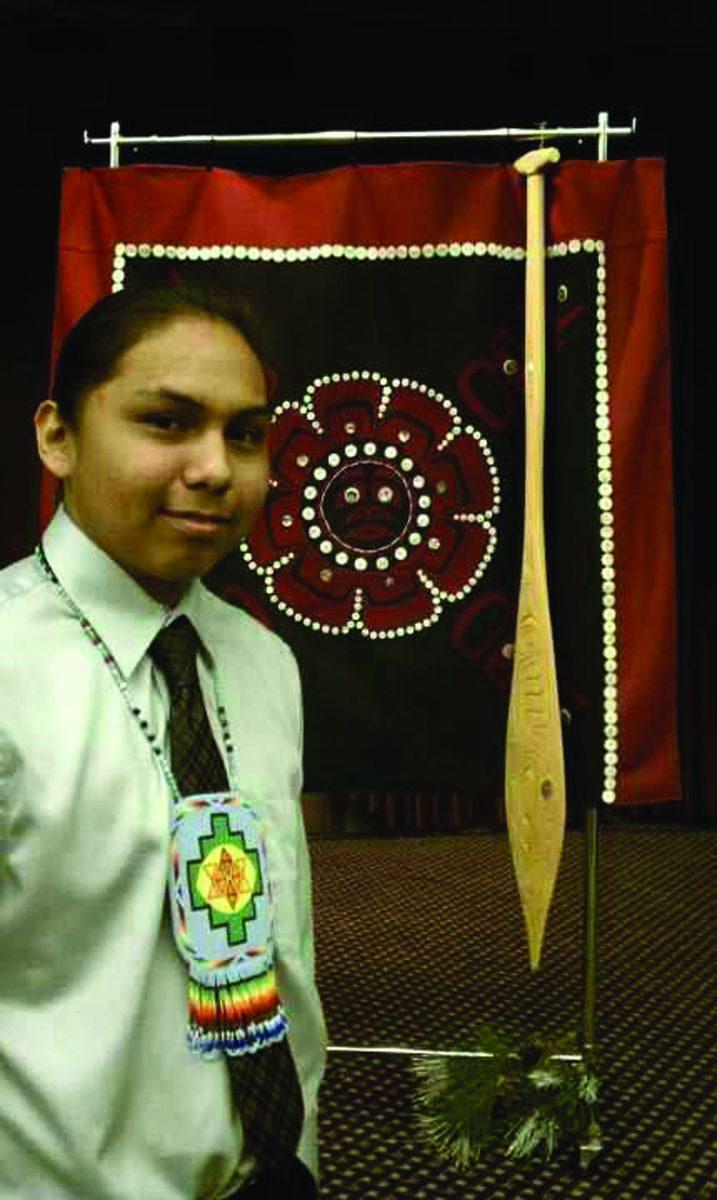

Being Native American was something Grant High School junior Marcus Johnson was proud of. And after seeing his young niece, Amelia Yahtin, dancing in her princess-like traditional dress, he began to take an interest in becoming more involved in his culture’s traditions.

He adored his two nieces, so much that he wouldn’t think twice about spending his allowance to buy them necklaces or take time to watch them dancing. Becoming involved in his culture was a way for him to connect to his heritage.

A new student to the school, Grant was going to be Johnson’s new path to explore. He had plans to join the wrestling team, the ski and snowboarding team, and pick up drawing again. He even had ideas of going to college.

But on Oct. 17, the morning before the PSATs, Johnson was headed to school when his heart stopped and his breathing became obstructed. He died at age 16.

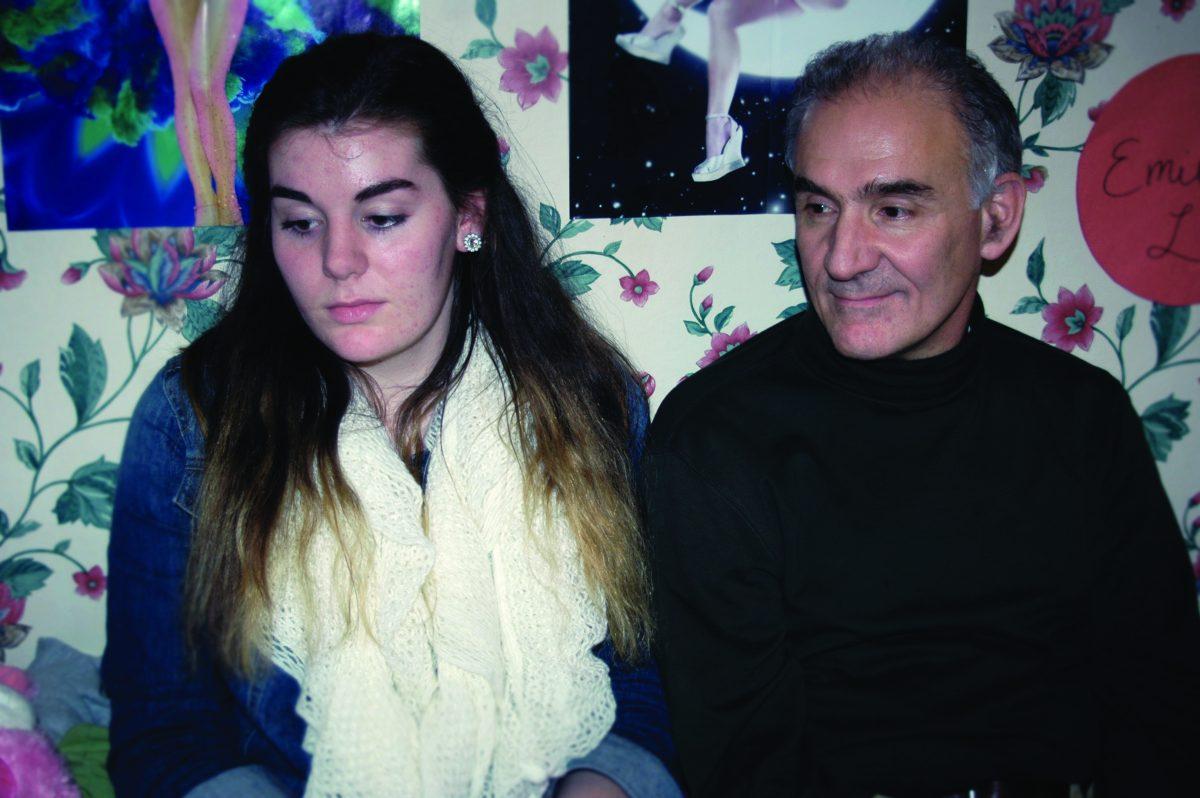

Earlier in the week, his foster father, Wesley Hutt, and Grant’s school nurse, LueAnn Beck, had been working with Johnson because he had been having difficulty breathing comfortably in school. Initially, it was thought that Johnson died from an asthma attack. But some say there might have been a problem with his heart.

“I really miss him,” says Dorothy Yahtin, Johnson’s biological mother. “It has been really hard on (her), too,” Yahtin says about Johnson’s sister, Chelsey.

Hutt agrees. His family is distraught, struggling to come to terms with their loss. “We were not ready to lose you,” wrote Maddie Hutt, Wesley Hutt’s daughter, on her Facebook wall. When the news was broken to the students of the Native American Youth and Family center where Johnson had attended school earlier in his life, everyone was shocked.

Johnson was born in Warm Springs, a Native American reservation three hours southeast of Portland that’s made up of various Confederated tribes. Johnson’s ancestors have been settled in Warm Springs for centuries, and his grandfather Chelsey Q. Yahtin Sr. spoke the Sahaptin language that was commonly spoken nearly 10,000 years ago. The elder descended from fishermen and the people of Celilo Falls located in the Columbia River Gorge.

The youngest of five, Johnson lived in Warm Springs as a young child with his father, Emil Johnson. His father died when Marcus was seven years old. His mother, Dorothy Yahtin, and his siblings were not together through the entirety of Johnson’s childhood. The dysfunctional family suffered from substance abuse and the kids had to be cared for by family members and the community.

Johnson lived with a foster family in Oregon City as a kid. It wasn’t until a couple years ago that Johnson moved to Portland. He enrolled in the Native American Youth Family center’s Early College Academy, participating in the after school programs.

Known as NAYA, the center has a tight-knit community of people who share similar history, background and culture. It’s a community as well as a school that warmly welcomed Johnson into the family. Johnson loved and appreciated being a part of the group.

Known as NAYA, the center has a tight-knit community of people who share similar history, background and culture. It’s a community as well as a school that warmly welcomed Johnson into the family. Johnson loved and appreciated being a part of the group.

It was through NAYA that Johnson met Welsey Hutt, a gang intervention and outreach worker. He also coaches youth basketball. Hutt had been working with and getting to know Johnson for about a year when he lived on the reservation. He was in need of a new place, a new home. Eventually, with contact from Johnson’s caseworker, they came to the agreement that Johnson would move in with Hutt and his family.

“It was a non-issue,” says Wesley Hutt, who is Native American and a member of the Hoopa Valley Tribe. “It’s kind of the Indian way. Our doors are open, our families are extended.”

Hutt’s two sons – Justin, 22, and Roman, 20 – and daughter, Maddie, 16, made Johnson feel welcomed, not hesitating to invite him to beach trips with all of their friends, and calling him “brother.” Wesley Hutt said Johnson really looked up to Justin and Roman, that it was a comfortable role for him to play as the younger sibling.

“Having Marcus stay with us, it was like having a joy in your house,” Hutt says. “We always have an open door, and that’s kind of how my kids have learned to be: welcoming.”

Johnson was starting a new life at Grant. It was an intimidating, daunting and difficult task for him, but it was equally exciting. He was always seeking adventure. “That was how he looked at life,” Hutt says.

Paige Smith is a youth advocate who worked with Johnson at NAYA. “He was my go to guy,” he says.

Johnson loved going to church and reading his Bible, drawing, Facebook, Michael Jackson, and Gears of War on Xbox. Above all, he loved to eat his mom’s fry bread. He was “outgoing and loved life,” Chelsey Yahtin says.

Theresa Smith of NAYA, another of Johnson’s youth advocates, adds that “although he had a good sense of humor, he wasn’t the class clown, and he wasn’t loud, but he just couldn’t be ignored.”

Smith recalls a time when they were driving to Seaside in a van full of kids from NAYA. Everyone fell asleep on the trek to the beach, except Johnson. He stayed awake and talked to Smith. They discussed what it meant to be a Native man. “He would really listen,” says Smith. “You could see the wheels turning in his head.”

Johnson learned to braid his hair in the traditional Indian way. He spent some nights braiding and unbraiding his hair, practicing until it was perfect. During his sophomore year, Johnson was chosen to work with an internationally recognized and award-winning artist Lillian Pitt. Pitt’s ancestry is from Wasco, Yakama, and Warm Springs, like Johnson.

He had always been a skilled drawer, but she taught him ceramics. They collaborated on a clay mask that took several weeks to produce. The mask was sold at an auction for the annual NAYA Gala, along with many other highly skilled pieces.

Was Johnson nervous about being at the auction? Sure. But the more stressful and initial problem he faced that night was that he did not know how to tie his tie properly. Theresa Smith of NAYA spent time before the event looking up on the Internet how to tie it, and together they finally figured it out. Smith says the collaboration with Pitt inspired him to continue his pursuit of the arts. He wanted to attend the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television after graduating.

Johnson also found joy in athletics. He joined the Chill program, a snowboarding program for underserved youth. The practice, he thought, would get him in shape so he could join Grant’s team. He also had picked up wrestling again.

He played basketball, too, even though he wasn’t as good as the other kids. Hutt remembers a game where Johnson got in for the last four minutes. And for four whole minutes, Johnson ran up and down the court, dribbling and passing, with a huge smile on his face. Every time Johnson got the ball, wild and crazy cheers erupted from his team. As the last seconds on the clock counted down, Johnson’s team was hollering at him to “Shoot it!” Instead, he passed the ball to a teammate, who made a three point shot to end the game.

He played basketball, too, even though he wasn’t as good as the other kids. Hutt remembers a game where Johnson got in for the last four minutes. And for four whole minutes, Johnson ran up and down the court, dribbling and passing, with a huge smile on his face. Every time Johnson got the ball, wild and crazy cheers erupted from his team. As the last seconds on the clock counted down, Johnson’s team was hollering at him to “Shoot it!” Instead, he passed the ball to a teammate, who made a three point shot to end the game.

When Hutt asked Johnson why he didn’t take the shot for himself, he said: “Because I wanted to get the assist.”

Johnson was also selfless. At overnight camps in Warm Springs, Johnson would take the time to gather up all his cousins and friends to spend time with them and make sure they were having fun before running off to do what he wanted. “He had a humble spirit,” says Paige Smith.

While Johnson was at Grant, he was able to make memorable impressions on many people in a short amount of time, most of them teachers. Nurse Beck helped him out if he was feeling sick, or if he came in for a brief visit and a quick hello.

Richard Brown, a Grant language arts teacher, thought of Johnson as one of the most thoughtful and kind-hearted students he’s ever had in his 15 years of teaching. Johnson was a student in Brown’s “Voices” course, which he thought absolutely fitting for Johnson. Brown recalls the time Johnson brought lyrics for a song from a play he had seen recently with his mother called “Ghosts of Celilo.” It was a play based on an area where his ancestors once roamed. The song was titled “Aw Na Winasha – Fishing at Celilo.”

Recently, Johnson and his biological family had been seeing each other more often. It was easier for them to enjoy each other’s presence with the specter of alcohol and drugs out of the picture. “We could just be ourselves,” says Chelsey Yahtin.

Dorothy Yahtin misses the long car rides the two of them used to take, listening to his Christian music the whole way. She says she will also miss the little things that Johnson did, like showing her how he could do Michael Jackson’s Moonwalk or have fun trading silly hats.

If Johnson were feeling down, he would pray. Prayer was an answer to everything. Johnson wasn’t just happy in church – he was exuberant. He would practically brag to his family about going to church, saying how he wished they could come and that it made him feel so good. Having religion in his life was never something Johnson was ashamed of: he was open about it because it made him happy.

If Johnson were feeling down, he would pray. Prayer was an answer to everything. Johnson wasn’t just happy in church – he was exuberant. He would practically brag to his family about going to church, saying how he wished they could come and that it made him feel so good. Having religion in his life was never something Johnson was ashamed of: he was open about it because it made him happy.

“He always knew what was right and what was wrong, and never failed to call people out on it,” Chelsey Yahtin says. “He was always smiling,” Hutt says, “it was a smile that could brighten anyone’s day.”

After the spiritual cleansing and burning of sage at NAYA, Marcus Johnson was buried at Warm Springs. Nearby are the burial sites for his father and six of his grandfather’s children.

For Marcus

Perhaps you were not meant to breathe in this world

but in the spirit world of your ancestors.

Here one moment.

Gone the next.

Still, your smile and pure heart shall remain

in the memories of those who knew you.

Your long black hair shall wave in the wind

as you fish with the ghosts of Celilo.

Fish on in peace.

Fish on in joy.

Fish on.

Fish on.

Richard Brown

October 17, 2012