It took Haley Knapp, a Grant High school senior, more than 20 tries to land a job. After filling out piles of applications, she took a job at Helen Bernhard’s bakery.

Senior Anna Aase spent the summer hanging out with friends and family before deciding to earn some spending money. She’s been applying since the beginning of school but hasn’t had any luck.

And Mitchell Rogers volunteers at the Oregon Humane Society, but now wants to earn money and gain work experience. “Volunteering showed me what the work force is like and I want to become a part of it,” he says. “I think it’s time to start applying.”

Finding a job for teens these days is difficult, especially since the economy is still dragging. When it comes to making money, Grant students and other teens are hard-pressed to find work. It’s not that teens aren’t worthy enough for work. There’s just no room for them.

Today, teens are competing with adults for jobs. The average unemployment rate for Oregonians who are age 16 to 19 was 29.7 percent in 2011, says Nick Beleiciks, an Oregon employment economist. Oregon’s overall unemployment rate averaged 9.4 percent.

How do students at Grant strike a balance? We talked to a handful of former and current Grant students who have tried to enter the workforce. They do it for different reasons, but in the end it comes down to gaining a new perspective when it comes to the real world. Here are their stories.

Haley Knapp: standing her ground

Haley Knapp remembers walking into Hollister at the Lloyd Center in search of a job. The lights were low and she was greeted by a strong perfume scent and loud thumping music.

She entered the room for the interview and saw three teens were already there. Two more followed, with just as many credentials. And everyone was desperate to find work. To make matters worse they were all interviewed together for one position at Hollister. Knapp left jobless.

“Looking for a job wasn’t necessarily difficult,” Knapp recalls. “You just have to fill out a lot of applications and wait for someone to call you. Staying motivated to go out and find a job application was the hard part.”

Knapp, a senior at Grant High School, kept going. She applied to more than 20 places. She started with large corporations like Hollister, Target and Starbucks. Then she moved on to Finish Line, Buffalo Wild Wings and Red Robin, followed by American Eagle and Subway.

For Knapp, searching for a job became such a hassle that she wondered if she would find anything. With the recession in full swing, she found herself competing with adults for jobs normally held by teenagers.

“Haley wanted to earn and manage her own income and she wanted to get some practical work experience.” Says Parvin Knapp, Haley’smother.

Knapp casually began looking for work last year and it became more serious this past summer. She wanted money to put towards a car and with only four classes she knew she’d have a lot of free time.

After having no success at the big companies Knapp turned to small businesses that had less competition. She finally got lucky, earning a job at Helen Bernhard’s Bakery. Her interview there was her favorite not only because she got the job but also due to the atmosphere.

“My interview for Helen Bernhard’s went really well,” she remembers. “I just went in and had a good conversation with the owner and was hired that day.”

She now fills her empty hours with serving baked goods. Best perk of the job? Free treats.

-Alyson Woolley

Nik Popp: a step ahead

Two years ago, the anxiety over money continued to eat away at Nikolaus Popp. He remembers hearing his mother tell his aunt that it was getting harder and harder to pay the bills.

Popp, then a sophomore at Grant High School, had to make a decision. In order to help his struggling family, he gave up a part of his high school experience and got a job.

“It wasn’t hard to get by but mid year I didn’t think I was going to get into any colleges that I was hoping for,” Popp says. “After waves of stress I kept discouraging myself. And when I got the acceptance letter from Oregon State University I felt relieved because my hard work was recognized.”

Growing up, Popp and his family had many financial issues. He says there were struggles sparked by Popp’s biological father who was trapped by an addiction to drugs and alcohol. Pawning their household items became a regular occurrence, leaving the family with a trail of bad credit and in a financial crisis.

As a kid, Popp was always really quiet and shy. “When he was a child, sometimes I thought he would never be able to talk,” says his mom, Linda Nguyen. “Our life has always been a struggle. It’s been a long, hard road.”

But Popp would do anything for his mom. “He was always very thoughtful and compassionate,” says Nguyen, who Popp considers the most important person in his life.

During his sophomore year, he got a job at a non-profit organization called IRCO. An agency designed to help families and children who are refugees or immigrants. He started out with filing and gradually began going on home visits with his supervisor, as well as analyzing data in the office and helping manage the budgets.

Families are able to get help from IRCO, receiving financial aid, help with housing and other basic services.

In other cases such as child neglect or abuse, they offer parenting skills or training on how to handle their kids. But if habits don’t change, the kids are removed from their home. Popp’s job is often very rewarding but once in a while frightening cases can emerge. “Some stories are terrible,” Popp says. “You look at a person and say wow, he really does this to his kid?”

Popp worked five days a week from the moment his classes at Grant ended until about 7 p.m. He also worked for five hours on Saturdays, the job took top priority. “I was late 72 times my senior year,” Popp says. “I’ve even gone to school about four times without any sleep.”

Graduating early and working so much had its downfalls. “I’d come home after work, eat, then shower, and normally have about one hour to do four hours worth of homework,” Popp recalls.

His grades started to dwindle down from As to Cs. Even his friends began to notice. “Nik would come to class more tardy then not, “ recalls Joel Schain, a friend of Popp’s.

After graduating, Popp realized how much of his high school experience was taken away from him. “Having a job and graduating early limits you from doing clubs and sports,” Popp says. “I didn’t have time for either of those.”

Popp remembers how Nancy Talvine, who worked in the office, used to help him when he was feeling stressed out. “She was someone I could talk to who actually wanted to listen,” Popp says. “For that, I want to say thank you.”

Today, Popp attends Oregon State University. A self-proclaimed “computer nerd,” he hopes to eventually get a job in information technology working with a technical support crew. He plans to major in computer science.

Popp thinks that when referring to economic class, many people are often misconceived.

“I have nice things because I worked for them,” Popp says. “Not because I’m rich or spoiled. If you want something, you have to go out and get it. Start with an idea and follow it with a goal.”

-Clara Howell

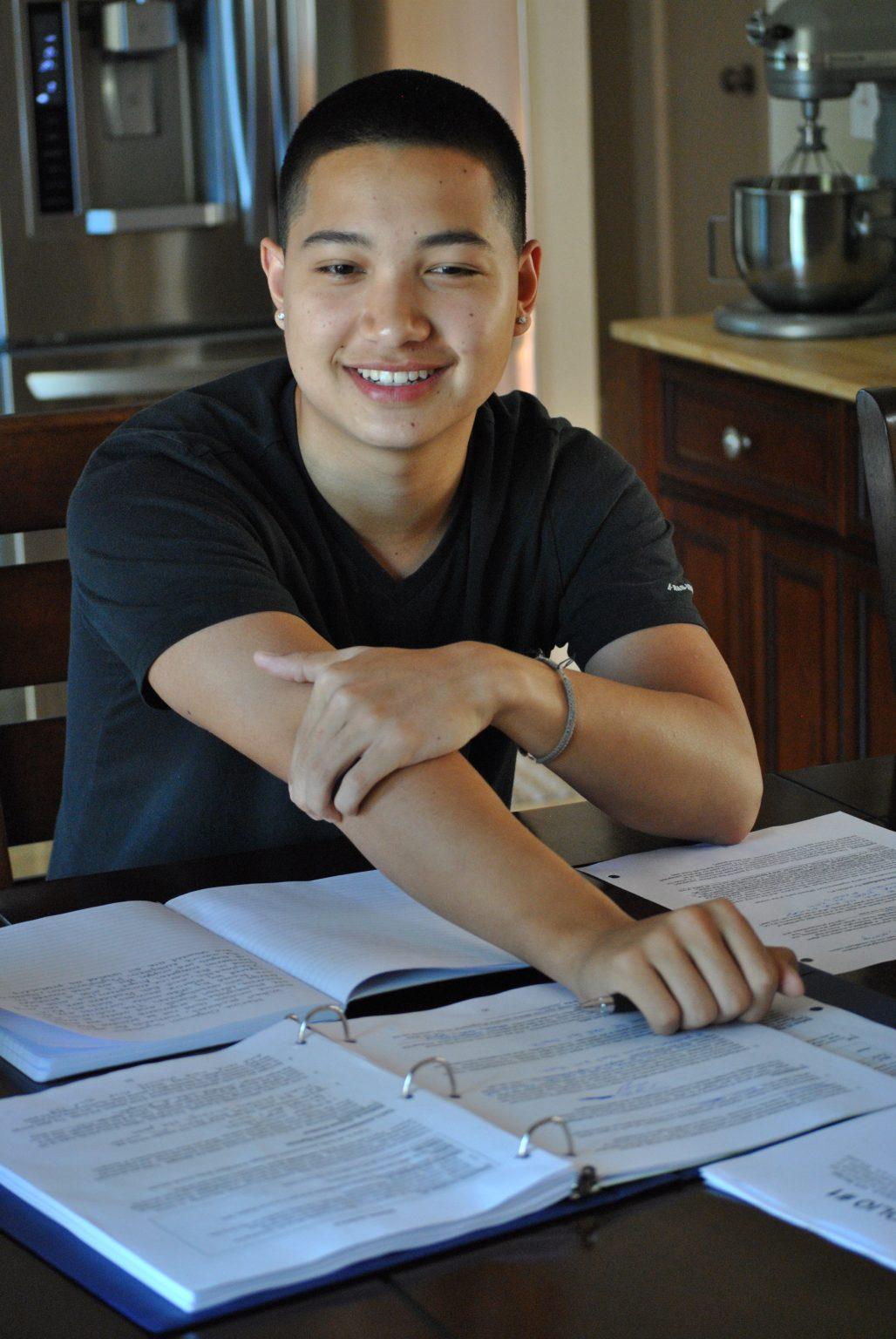

Drew Tamiyasu: striving for independence

Last year, Drew Tamiyasu and his friends crowded around a table at Taste Tickler, waiting for their orders. He had nothing in his wallet except his school ID and he recognized that this was becoming a recurring pattern: no money, a bunch of friends always gathering, and no food for him.

“All the food smelled so good and I was basically drooling,” Tamiyasu says. “But I just had to sit and wait.”

That’s when he knew he should probably get a job. After being rewarded the opportunity to work at the Iron Horse restaurant in Southeast Portland by family friends, his mom told him he’d get no more spending money if he didn’t accept the offer, so he took the position as a bus boy and decided to bring in the bank for himself.

“I need money to buy a car, clothes, and lunch,” he says.

Before he worked, Tamiyasu was stuck at home doing basic chores in order to cop a few bucks. He would occasionally have to mow the lawn, clean and take care of his own laundry.

“When he was given the opportunity to work, I knew it was time for him to gain independence and responsibility,” says Tamiyasu’s mom, Tracy Andersen. “I wanted him to understand the value of a dollar.”

When he started the job, he had to take the bus to work. That meant managing his time accordingly, but it didn’t always work. “I used to take an hour bus ride to work,” Tamiyasu says. “The bus sucked. I would miss buses and end up being late for work and it took so long.”

But his manager was usually pretty “chill” about it. Although he was occasionally later for work, he was sometimes late getting home. Tamiyasu remembers when the busses stopped running on his way back from work one night and he had to walk six miles to get home—three hours later than expected.

“That was one of my biggest motivations to finally get my license and a car,” says Tamiyasu, who bought a 1986 Volvo last summer. “Now it’s just a 25 minute drive,” Tamiyasu says.

Now, Tamiyasu works eight hours a week on average. “Work isn’t flexible with its hours, “ Tamiyasu says. “It varies, so some nights I’ll work until ten and others I’ll get done around eight or nine.”

On the downside? “I’m usually lacking sleep,” Tamiyasu says. “It hurts my grades when I’m too tired to do my homework.”

-Clara Howell