At Grant, students complain a lot. School sucks, we say. We have too much homework, weekends are too short, classes are too long. It’s a never-ending cycle. But this summer I learned something: we never really stop to think about how lucky we are.

I volunteered at a camp in Michigan for young people who were 14 to 20 years old. They never complained. They didn’t have any gripes. They didn’t stress out about their social scene. The campers were completely blind, visually impaired, or deaf.

I got this opportunity because my aunt works at this camp that is set up to teach skills for independence to teenagers with vision restrictions or who are deaf. I had no idea what to expect. Being so used to hanging out with people who have vision and hearing, my biggest fear was saying something offensive, like “Did you see that?” or “Look at that color.”

I braced myself to spend my time at the camp walking on eggshells. But when I got there the first day, I met a girl who wanted to talk about her love for Nicki Minaj. A bunch of kids talked about the Summer Olympics. One girl fancied herself as a makeup artist. The campers were so similar to people I know from Grant; the only difference was their diminished eyesight or that they couldn’t hear.

The idea was to make everyday life activities easier for the students. Things that a person with vision would consider completely mindless can be surprisingly difficult for people who can’t see, like counting money, crossing the street, cutting food, opening a package of cookies, or even preheating an oven.

As I learned more about the struggles they go through every day, I felt guilty about complaining about doing chores. Everyone has pretended to be blind at one point or another, covering their eyes for a couple of seconds or trying to perform a task without looking. But at the camp I could see the reality, and it’s a lot more difficult than you would imagine.

Being blind, the kids don’t judge you on what you look like. To them, it doesn’t matter what you are wearing, how big or small you are, what color your skin is or anything else related to your appearance. Their opinions of you are based completely on your personality and how you treat other people. Shouldn’t that be the way we interact with everyone?

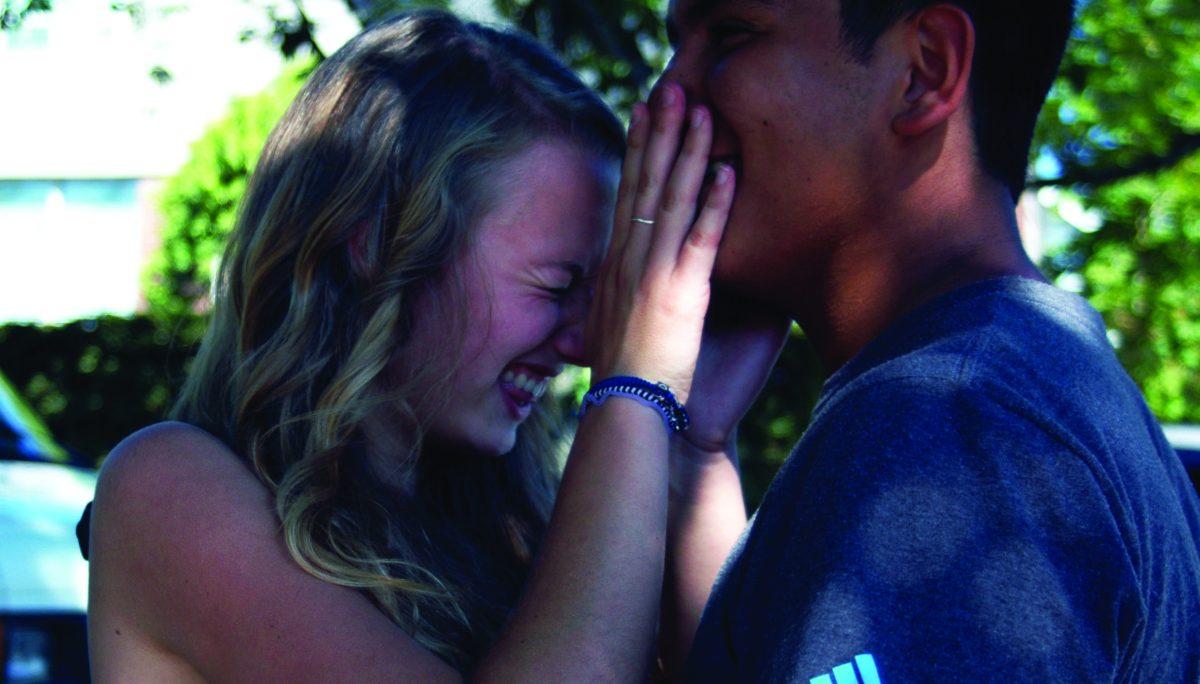

One of the days of the camp featured dancing. When the music came on, we moved our bodies however we wanted. At the end of the day, I found myself running around the room flailing my arms with colorful scarves in my hand. Nobody cared whether I was good or not. We were all there dancing together and that’s all that mattered. My dance partner, Tanis, was blind when he was born. His blindness really bothered him when he was younger, but now he is used to it.

He graduated high school, has a job, loves to travel, and has friends who are both blind and not blind. When someone asked him if he would gain vision if he had the chance, he said he would for one day just so he could see what a human being looked like. There is a whole spectrum of life that he and the other blind people are missing out on. That doesn’t matter to them.

They set aside the daily struggles of their blindness and they are just like us. But one big advantage they have over us is that they have a way better grasp of what can hold you back. ♦