On an icy ledge atop Africa’s Mt. Kilimanjaro, Quentin Carter teeters on the threshold of a 400-foot drop. As he follows his fellow climbers up the fourth tallest peak in the world, this Grant High School student is closer than the majority of us have ever been to death: one misplaced step.

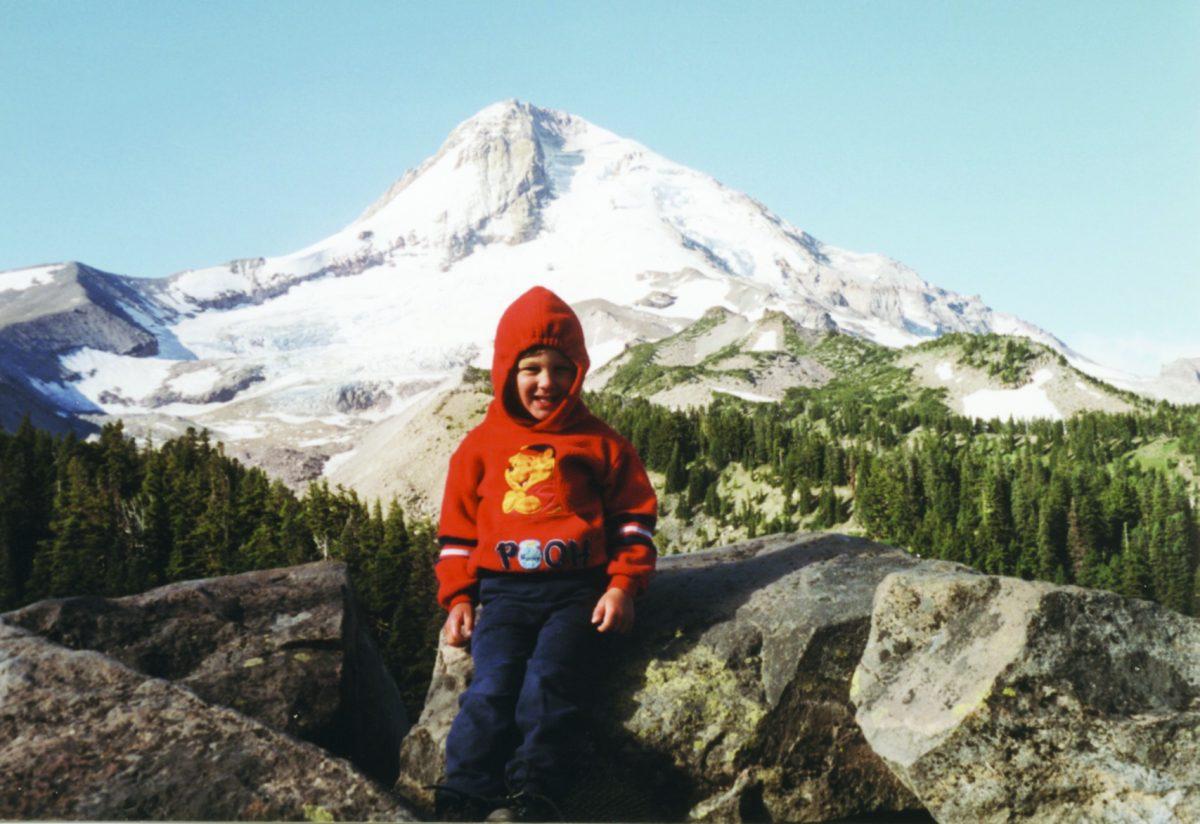

Some people play soccer, run, create art or read. Grant senior Quentin Carter, 17, goes on adventures. Climbing since the age of two and a half—when he garnered the nickname “Dusty” for sliding his feet along the trail—Carter has already accomplished more than most mountain climbers do in their lifetimes.These days, Carter boasts the endurance cross country runners would die for and sharp instincts honed from years of experience. With guidance from his father and countless peaks under his belt, Carter has ditched Dusty and is now known for a coveted hard-earned attribute. True grit.Carter’s dad Matt took his son out at an early age on short hikes around Mt. Jefferson. Fast-forward to age four: Carter successfully climbed a glaciated peak and became the youngest person ever to be granted entrance into Portland mountaineering organization the Mazamas.

From there, Carter’s passion for mountainering took off.

Although a six-year-old climbing major glacial peaks was extremely rare, Quentin’s young age never got in the way of the climbing. By the time he was eight years old, he was the youngest person ever to receive the Guardian Peaks Award for successfully summiting Mt. Hood, Mt. St. Helens and Mt. Adams.

Climbing companions always enjoyed the company of a kid, and young Carter erased any lingering doubt as he proved himself capable over and over again. “He would do these amazing long days,” remembers Matt Carter, “and he’d just keep going, he never quit, he never complained.”

While many kids spent summers on the beach or in the park, Carter and his dad trekked to the highest points in the Pacific Northwest, often climbing up to five mountains per summer.

Climbing mountains is no hike in Forest Park. To get in condition, Carter says, going to the gym and running on the treadmill is not enough. “There will be people who apply for climbs, people like cross country runners—super, incredibly fit—but then they get on the mountain and they’ll have their ass handed to them because it’s a completely different game.”

As far as training, “the best practice and preparation for climbing mountains is climbing mountains,” claims Carter.

Forever seeking new adventures, this summer Carter, his dad, and three other Mazama climbers traveled to the African country of Tanzania to climb Mt. Kilimanjaro—a 19,341-foot peak that is the tallest mountain in Africa and on Carter’s resume.

Climbing with a company called Embark, Carter’s group took the most difficult and technical route.

On the steep slopes of Kilimanjaro in an area aptly nicknamed “the death zone,” a couple of streams had frozen over in the middle of the night forming a slick sheet of ice. The only way to get across alive was simple: don’t fall. “You can’t kick your boot into it,” he remembers. “You can’t get a step in it, you just have to be really, really, careful or else—down you go.”

But Carter takes the danger in stride, “that’s the real fun climbing,” he says. The danger, he assures, doesn’t turn him away from the sport he loves. “You’ll most likely come out alive as long as you’re willing to stop and turn around before you die.”

After fifty miles and seven days of climbing, Carter and his dad reached the African summit.

Many people can’t even fathom what it would be like to be on the top of Mt. Hood—Carter’s personal playground—let alone the fourth tallest mountain in the world. But Carter just shrugs. He says summiting for him is not the amazing, inspirational, music-worthy moment many of us might think being on the top of the world demands. “Alright,” he thinks as he gazes out across the craters, ice fields and layers of clouds below him, “what’s next?”

The rewards for climbing don’t just come as plaques, or bragging rights—of which Carter has many. Carter’s dad emphasizes the benefits that mountain climbing has on character. “You have to be able to endure a certain amount of hardship. It develops your ability to just suck it up and do things, because once you’re out there, the only way you’re going to get back is with your two feet…there’s no plan B.”

Eventually, Carter hopes to summit K2—one of the most difficult mountains—and after checking Africa off his list, is motivated to climb the other six tallest mountains in world.

Seeing his son succeed is terrific, says Carter’s dad. “When he was much younger I was always coaching and guiding him, but now he just taunts me for not being as fast as he is. He out climbs me now, so I’m just thinking he can start carrying all the heavy stuff.”