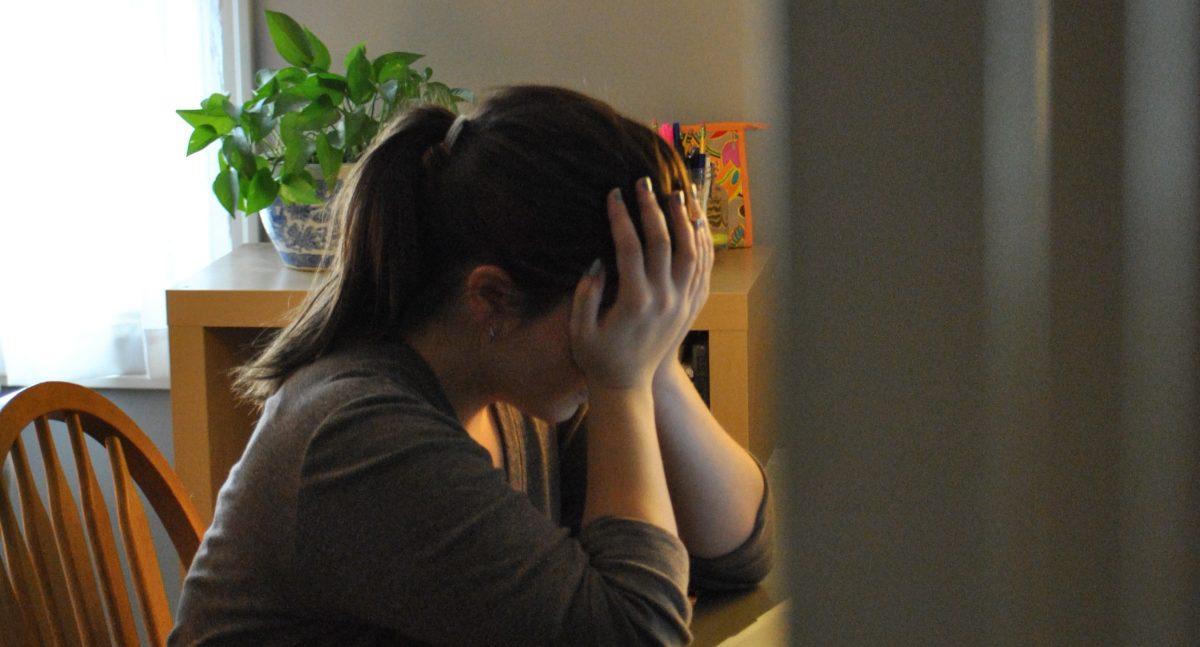

A Grant student heads home from a long day at school. Opening up her laptop to start some homework, Facebook pops up and a new string of messages awaits. Her heart drops. A ‘best friend’ has sent a paragraph-long attack about her appearance. “Nobody likes you,” the message ends. Confused and hurt, she tries to finish her homework but can’t focus. The next day, she doesn’t want to go to school out of fear of being confronted in person.

Bullying in schools has been a problem for decades. It used to be the stereotypical bully was someone who walked up and stole your lunch money. But with the wildfire spread of technology, teens now have unlimited access to each other. So even when an adult is sitting nearby, teens can lash out with a text, tweet, Facebook message or email aimed at making another student’s life miserable.

It’s called cyberbullying. And it’s happening across the nation in record numbers. According to a national survey, one in three kids has been threatened online. Those threats sometimes have catastrophic consequences. Students spiral into depression. Sometimes they harm themselves. Many students have committed suicide because of the way they get treated by their peers.

And the bullying can sometimes create a domino effect: if students are bullied, they might repeat the behavior toward others. Grant High School experienced that last year when the incident involving hazing on its sports teams came out. The true undercurrent of the problem was bullying. Students went viral, gossiping and arguing about the situation, leaving Grant grappling with its first public glimpse of cyberbullying.

Ask Curtis Wilson, Grant’s vice principal of discipline, and he’ll tell you it’s a mistake to think this kind of thing as exclusive to a sports team or any one group of students. He deals with numerous cases of cyberbullying each year. One case involved two girls who would constantly insult each other over the internet. “In the end,” Wilson says, “the only thing that got us through this is the fact that they graduated. They hated each other for a whole year, and they did it all through Twitter and Facebook.”

“When I was in school,” Wilson recalls, “the bully would have to find you; they would have to catch you. Now, if they have your phone number, they just text you. So if you want it or not, you’re gonna get it.”

Wilson deals with this almost daily: “That’s what we do most of the time,” he says. “We put out fires.”

Stopping cyberbullying is extremely difficult. The key problem is that everyone has access, and getting kids to put down their phones is as tough as getting rid of the national debt in a day. According to national statistics, 69 percent of students own a smartphone or computer, and most of those students are active on social media websites.

In a big school, it can be hard to monitor every single instance of bullying, especially when each person defines it a different way. So how does the school deal with problems of bullying and cyberbullying? There is only a short paragraph about harassment, bullying, hazing and sexual harassment in the Portland Public Schools’ Student Responsibilities, Rights, and Discipline Handbook. And although PPS has a zero tolerance for bullying and harassment, if students don’t report their problems to the administration, they are rarely handled.

One way Grant will fight bullying and harassment is through the upcoming Bullying Prevention Summit, set for Sept. 19 and sponsored by Multnomah County Commissioner Loretta Smith.

The summit, organized by Smith and her staff, will teach Grant kids about the dangers of cyberbullying and will hopefully encourage them to stop.

Smith wants to create awareness for students who are being bullied and to make the school a safe space. She wants to empower students to be comfortable with themselves and to send a strong message that any form of bullying and harassment will not be tolerated.

Emotional bullying can be scarring. “You laugh at someone because they may not be an athlete, may not be as cool as the other kids, may be poor,” says Smith, “but you don’t know their situation. We want you to be the best you can be minus all of the negativity.”

Principal Vivian Orlen acknowledges that we have a bullying problem at Grant. “In my two years in the school,” Orlen says, “there have been different instances where students have not felt safe or respected. I hope that we get a way to launch an examination of our school and the practices we have in our school.”

One of the administration’s most formidable struggles is dealing with teen’s unlimited access to technology. Walk down any hallway at Grant and you will see eyes glued to phones, fingers rapidly typing or scrolling. “People are just meaner about it because now you can hide behind a computer,” Wilson says.

It is extremely challenging for the administration to take action within PPS protocol. If it is something that students are doing on their own time, it’s harder to find the authority to discipline a student. “If we can show a pattern of harassment or that it disrupts the environment of the school,” Wilson says, “we can take action.”

With the magnitude and extent of modern cyber attacks, bullying quickly spirals out of control. Bullies no longer have to face their victims, and can say

harsh things with fewer consequences. This crucial disconnect results in bullies not fully understanding the impact of their words.

Shannon Hoffman is a staffer in Smith’s office. She remembers getting bullied in high school. As the only girl on her school’s wrestling team and she was harassed emotionally and physically by her teammates. “I was 6-foot-1 when I got to high school,” Hoffman says. “I stood out, so I experienced my fair share of being bullied and witnessing it.”

The sharp increase in the amount of bullying resulting in teen suicides has coined a new term: bullycide. In the past ten years, teen suicide rates have increased about eight precent, according to Science Daily research.

With this change in mind, PPS is trying to establish a bully-free culture in a decade where inappropriate online behavior is the norm, and all too often blurs into real interactions.

The increase in bullycides and bullying has provoked notable preventative action campaigns, such as the recent film “Bully,” produced by Lee Hirsch. It’s a documentary film following five students who face bullying every day, hoping to open the eyes of viewers to the dangers of bullying.

The “It Gets Better” campaign, a national project involving homemade videos and testimonials by bully victims from the gay and lesbian community, has become popular on the Internet.

Smith wants Grant’s Bullying Prevention Summit to accomplish a similar goal. She is alarmed at how fast bullying can escalate, especially among girls. “I think girls are getting violent,” she says. Shoving each other, threatening each other, beating each other up on the bus, and it’s not cool.”

Personal experience drives Smith to fight against bullying.

She recalls taunts about her thin build and having larger lips. She witnessed bullying almost daily at her school in Michigan, but didn’t always step in for fear of becoming the target herself. “I wish that I had the strength to stand up to bullies for other people,” Smith says.

She wants students to know that the suffering from bullying can really define someone’s life.

“If we could get everyone to delete all the negativity off their electronic pages or accounts,” Smith says, “that can be the beginning of people making a footnote in their heads to say: ‘I shouldn’t be doing this.’”

Related Stories:

Breaking down: Senior Hanna Olson recalls being bullied and the scars it left her with. Click here to read more.

Bouncing back: Senior Hayley Jameson looks back on her experience being bullied, but learned to move on. Click here to read more.