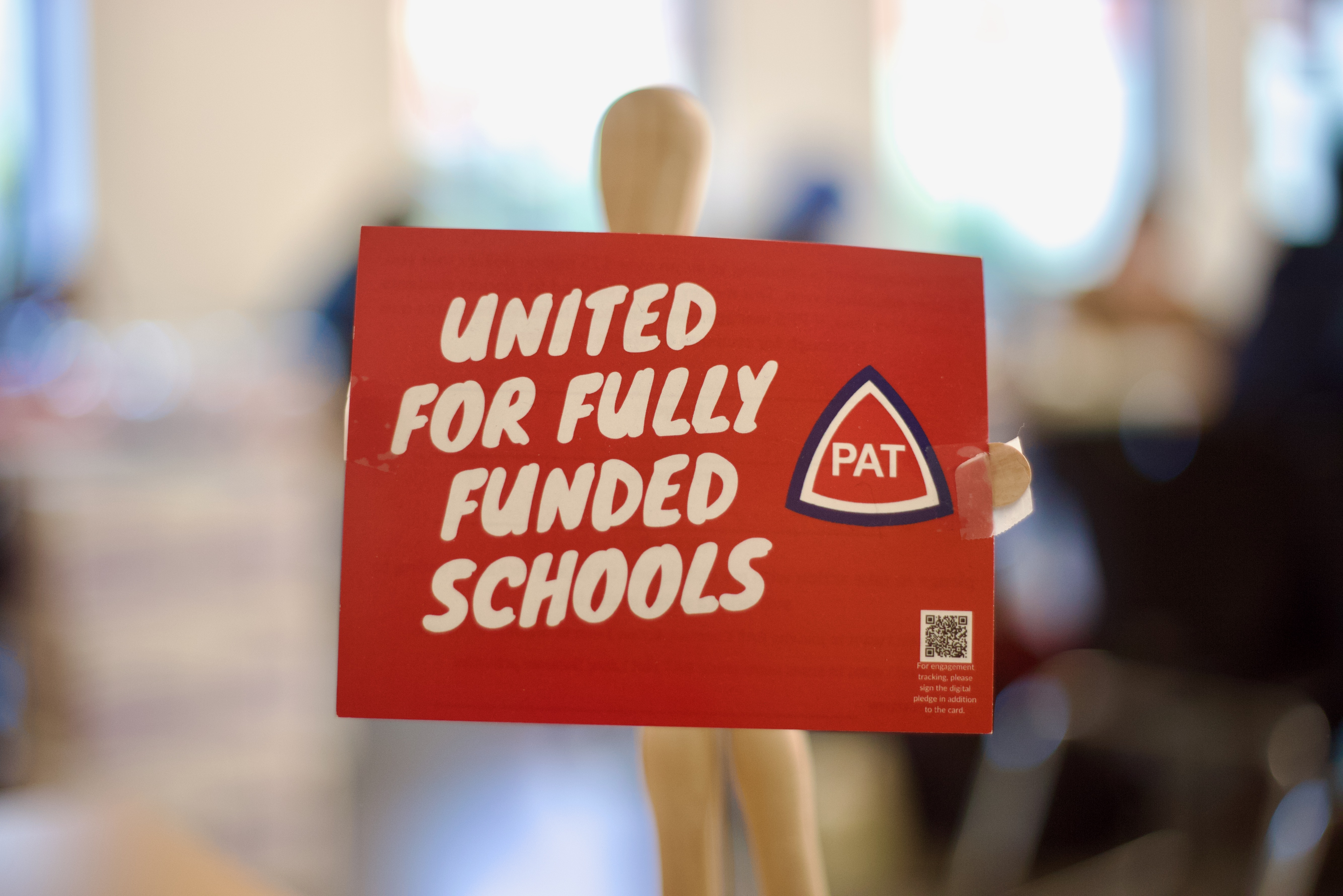

On Nov. 1, 2023, the Portland Association of Teachers (PAT) — the union representing educators in Portland Public Schools (PPS) — walked out on the picket line for the first time.

Each morning, teachers were required to check in at their school’s picket line using site-unique QR codes; they would then receive a $120 daily relief-pay stipend from the Oregon Education Association, the statewide teachers’ union. According to the PAT vice president, Jacque Dixon, QR-code data show consistent picket numbers of 3,500–3,600, dipping only in the strike’s final few days. Dixon alleges that those numbers are “unheard of when you have a strike that long.”

“The way that we saw our community come out and really support, for me, is one of the things that kept me going,” says Dixon. In interviews, multiple PAT members also expressed strong feelings of support from the community, including families bringing soup, rolls, muffins and hot chocolate for educators.

In every contract bargain, says Bill Wilson, a Grant High School science teacher who chaired the PAT bargaining team that narrowly avoided a strike in 2014, “the two biggest issues for nearly every teacher are always salary and workload.”

Both were leading reasons for the 2023 PAT strike.

Of the six largest school districts in the Portland, Oregon, metropolitan area, PPS teachers’ base rate was the second-lowest in 2022–2023, at $50,020 annually. PPS’s highest-paid teachers — those with a master’s degree, 12 years of experience and 45 additional course credits — were paid an annual salary of $97,333, the least of all six districts.

PAT repeatedly argued that teacher’s salaries were not keeping up with inflation. In pre-strike proposals, the union asked for a 21.5% cost-of-living adjustment over three years.

High school teachers have a teaching load threshold of 160 students. For every five students over that threshold, teachers’ salaries are increased by 1.5% semesterly. This increase is at the base rate — $50,020 — not a teacher’s normal rate.

Teaching load has been a persistent point of tension. During bargaining sessions early in the 2023–2024 school year, PPS and PAT — which represents 3,587 educators — both recognized that class size was one of the most contentious issues needing resolution.

Despite agreeing on what needed solving, Megan Schlicker, a counselor at Grant, felt the district was “not taking negotiations seriously” in the first months of the 2023–2024 school year.

“The only thing that was going to make a difference was us striking,” says a Grant teacher who asked to remain anonymous.

On Nov. 20, as the strike approached its third full week, PAT announced in a bargaining brief that after almost 24 continuous hours of bargaining, the PAT and PPS bargaining teams had reached what they believed to be a tentative agreement. The PPS Board of Education then “unanimously rejected the recommended settlement sent to them from their own bargaining team,” the PAT bargaining team alleged. “This crisis of their own making unnecessarily prolongs the strike, and demonstrates the inability of district leadership to govern Oregon’s largest school district.”

In a press conference streamed by KGW on Nov. 20, Gary Hollands, the chair of the PPS Board of Education, denied PAT’s claim: “I want to be clear that our board did not reject the whole proposal,” he said, “and there was not a tentative agreement in place.”

In the news conference, another board member, Julia Brim-Edwards, said only three of the seven board members had been present for that session. According to the district, only the whole board can accept or reject a proposal.

In an interview, PAT President Angela Bonilla said that three board members — not the unanimous board, as the PAT’s bargaining brief contended — had rejected a jointly agreed-upon settlement, preventing the agreement from reaching a public vote.

Bonilla called the settlement rejection “a once in a lifetime level of dysfunction that no one had prepared for.”

When asked how such stark disagreements on bargaining facts arose, Bonilla attributed it to “folks who haven’t slept in 25 hours, and then are trying to do press conferences right after.”

In the following days, tensions only worsened. Toward the end of bargaining, say Bonilla and Dixon, both sides agreed to a media blackout. But Hollands continued to post specifics of negotiations on Facebook. “(Hollands) was posting stuff on Facebook that was supposed to be confidential, that we had jointly agreed upon being confidential,” says Bonilla. “The board kind of went rogue and started talking about things without the full context.” (Hollands and the board’s vice-chair, Herman Greene, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Educators interviewed felt that a majority of the strike news coverage was biased against PAT.

Some of this skew may be due to the stark contrast in PAT’s and PPS’s media resources: PAT’s communications is volunteer-only; PPS’s communications (comms) department has nine full-time employees and a budget of $2.3 million — the largest communications team of Oregon’s largest three districts and more than double the second- and third-largest districts’ comms spending.

“The PPS communications budget is equivalent to the school-based budget for Creston Elementary,” says Dixon. (Creston is a K–5 school in Southeast Portland with approximately 275 students.)

Bonilla says the PPS communications department’s focus has been, “‘How do we protect and uplift the reputation of the district?’”

Asked if she felt the district’s focus on protecting itself led to it intentionally misleading the public, Bonilla is unequivocal: “Yes,” she says, chuckling. “Absolutely.”

To counteract this, PAT encouraged members not to read news that wasn’t from the union. A chant was developed: “If it doesn’t come from PAT, don’t believe that.”

It worked: Educators interviewed said they were more likely to believe news from PAT than PPS.

“We’ve had to build a culture of, ‘Ask your union,’” says Bonilla, because as an educator reading the news, “you’re not always getting the full information.”

Some educators were more wary of making PAT their sole source about strike news. “There’s truth in both sides,” says Schlicker, but “you couldn’t believe all of one or the other.”

How can PAT assure the public that they haven’t abused the “ask your union” culture to mislead their members, as they accuse the district of doing?

“Our district communicates in ways that serve the district’s interests,” says Bonilla, “and there’s a point where the district is taking care of the district and not necessarily looking at what’s best for each student, or each school.”

“Union leadership, they’re all teachers. They work or have worked in PPS buildings,” says Scott Blevins, a Grant English teacher and PAT building representative. “It isn’t like the things that they’re saying are coming from a place of lack of knowledge.”

On Nov. 26, PAT’s bargaining team announced that it had reached a tentative agreement with PPS. The team made an unequivocal pronouncement: “We won.”

When Wilson heard what the agreement was, “It was absolutely shocking,” he says. “(The agreement) to me indicated that our leadership didn’t know.” What Wilson says the union “didn’t know” is the answer to a question central to the strike: How much money did the district have?

In September 2023, PAT released a report, “A Manufactured Crisis.” It stated that PPS’ general fund balance — “the district’s main pot of spending money” — which must contain a minimum reserve for emergency use, had grown to $99 million by the end of 2022. The document argued that PPS could spend $53 million of that and still be above the fund’s required minimum.

On Nov. 2, 2023, PAT made a post on Instagram alleging that PPS had omitted over $20 million yearly dollars from budget forecasts. According to KGW, the district adopted its 2023– 2024 budget before receiving the $20 million from the state; while the money was missing in some communications, it was present in others.

Educators interviewed felt that PAT was mistaken about how much money the district had.

“You’re holding out thinking and being led to believe that there was money,” says Wilson, “but the reality is, there wasn’t.”

The conversation about how much money the district had “has never been like, ‘There’s all this additional money,’” says Bonilla. “It was always, ‘This is a crisis of priorities.’”

A little over a minute later, Bonilla characterized the union’s bargaining position toward PPS as, “When will you agree that you have a pot of money you’re willing to spend?”

“There was a failure of union leadership to properly direct the bargaining and lead us to strike over issues that were attainable,” says Wilson.

According to Bonilla, the agreement’s biggest wins include: the addition of a Special Education article requiring the district to provide additional support for students needing it; the expansion of the Rapid Response team for cases of unsafe or disruptive student behavior by eight positions; lower class size thresholds for K–5 teachers; and the creation of class-size committees consisting of educators and parents to address overloaded classes and caseloads.

What Wilson found so shocking about the agreement was the 13.75% cost-of-living adjustment over three years — compared to the 21.5% from an early proposal — and the lack of class-size language. Blevins says that the agreement’s lack of hard class-size caps is disappointing, as it’s one of the biggest reasons many teachers initially voted to strike.

Under Oregon law, class size is only a mandatory bargaining subject — meaning PPS has an obligation to bargain on it — for Title I schools, which have more students with risk factors like poverty or high mobility. To qualify as Title I, 33% of K–8 schools’ students must be receiving state support services; for high schools, the threshold is 46.9%. As of January 2024, 20 elementary schools, five middle schools and zero high schools qualified as Title I in PPS.

According to Bonilla, 3,158 members voted to approve the tentative agreement; 177 voted against it.

Wilson voted to approve. “There was nothing more to be had,” he says.