A sea of slimy green washes over a crowded shore, coating sand and nearby rocks with a gooey film. Dogs jump into the river to cool off and their owners follow behind them, wading into the water until they are submerged up to the waist. Little do they know that an insidious poison is wrapping itself around them.

Each summer, thousands of people flock to the Willamette River’s shores to go boating, swimming, sunbathing or any other number of outdoor activities. The river has gained a reputation over the years for being dirty and unsafe, yet the masses continue to gather.

Now rivergoers face a new threat — a deadly one. Appearing mucky green, red, blueish or brown, toxic concentrations of cyanobacteria known as Harmful Cyanobacteria Blooms (HCBs) form in the Willamette’s still waters in late summer. The slimy blooms damage marine ecosystems and are harmful to both humans and animals.

In order to develop into thick blooms, HCBs require warm, stagnant water and an excess of nutrients. An average river has few places with significant sections of stagnant water to appropriately harbor a bloom, but, in the Willamette, a unique and partially artificial feature allows the cyanobacteria to grow quickly and densely.

This area is known as the Ross Island Lagoon.

Ross Island is the biggest of the Willamette’s four islands. Located about one mile south of downtown Portland, Oregon, the lagoon has been a hotspot for HCBs for years.

The Ross Island Lagoon has an extensive industrial history. Beginning in 1926, sed-

iment mining in the lagoon, conducted by Ross Island Sand & Gravel Co. created pools where water could not circulate properly. The mining operations’ effects were amplified by a man-made embankment constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers that same year. This extensive exploitation of the lagoon caused the river flow through the lagoon to be dramatically disrupted.

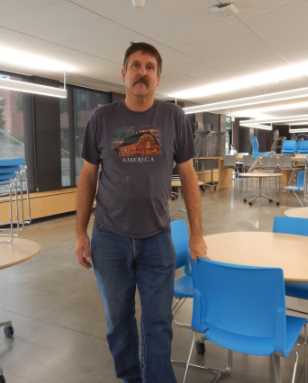

“The conclusion was that Ross Island Lagoon is a pond inside of a river,” Wille Levenson, the ringleader of a nonprofit organization, the Human Access Project says. “It’s very unusual for harmful algae blooms to form on rivers.”

In 1979, Ross Island Sand & Gravel Co. was required to begin filling in parts of the lagoon with imported sediment in order to restore land; they were also instructed to bury contaminated sediment in sealed containment cells.

One of the cells was breached in a later mining operation in 1999, releasing contaminants into the river. Contamination made future riverbed operations far more complicated and unsafe, with Ross Island Sand & Gravel Co.’s mining efforts ultimately coming to an end in 2001. Goals for reclamation of the lagoon were set in 2002, with a deadline of 2012.

However, multiple state agencies were unable to properly enforce the original deadline, and it was recently pushed back to 2033.

In 2015 — shortly after the original deadline had passed — a summer of extreme heat exacerbated the Willamette’s HCB issue.

For eight years running, HCBs have been tracked and researched thoroughly in the Willamette. Desiree Tullos, a professor of Water Resources Engineering at Oregon State University, has been actively monitoring the river’s HCBs. She says, “DNA analysis that we’ve done has demonstrated that the lagoon essentially is like the cyanobacteria factory, and it’s sort of creating the algal cells and just redistributing it to the rest of the river.”

While its stagnant waters were influenced by human activity during early-20th-century mining operations, water temperature and nutrients in the river are a more direct result of contemporary climate change. Increasing summer heat adds to the Ross Island Lagoon’s warming waters, making them increasingly habitable for the HCBs. The two nutrients that feed the cyanobacteria in the Willamette River are nitrogen and phosphorus, both of which are found in wastewater, agricultural runoff and even firefighting chemicals.

Since 2015, the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality has been researching HCBs in partnership with activists and scientists to propose initiatives to improve river conditions. Ownership of the Ross Island Lagoon lies in the hands of Ross Island Sand & Gravel Co. and the City of Portland. Solutions require funding and cooperation between the owners and outside organizations.

The underlying objective of many proposed solutions to HCBs is to get more water flowing through the lagoon, which would help prevent water from warming further and reduce the stagnation that HCBs need to thrive, ensuring a healthier future for the aquatic life in the river.

The lagoon in its current state provides a threatened habitat for a protected species. “Juvenile salmon, as they are headed out to the ocean, need shallow water with a lot of plants in it,” Tullos says. “(The Ross Island Lagoon) is critical to the juvenile salmon as they head out to the ocean.”

Chinook salmon found in the Willamette are protected under the Endangered Species Act, meaning any action taken against HCBs cannot interfere with their habitat. Solutions must simultaneously stop HCBs and preserve juvenile salmon habitats, making eliminating HCBs all the more difficult.

The proposed creation of a flushing channel through the lagoon would restore partial water flow to the area. The flushing channel would cut through the west side of the lagoon and would likely be lined with rocks, says Tullos. It would also provide an entryway for salmon. This plan is not only permanent and reliable, but would also require minimal maintenance.

Many different groups must cooperate to implement these solutions. Levenson says that “90% of (my) work as an activist is getting adults to cooperate with each other … People protect what they love. I think what happened was the river was turning green, but people weren’t noticing it.” He continues: “The more we can get people to interact with the river, the more likely they are to participate and care.”

Apprehensiveness about going into the Willamette is common, especially after Oregon Health Authority (OHA) cyanobacteria warnings about “toxins that can cause illness in humans and animals.”

Elsa Warner is a Grant High School student who frequents the Willamette as a part of Rose City Rowing Club. She says, “Once I think about (the conditions of the Willamette) more, it makes me less likely to want to row there.”

Like many Portlanders, Warner was unaware of the impacts that HCBs were having on the Willamette River. She had known for some time that there were issues regarding sewage and pollution but the concept of toxic blooms in the Willamette was unfamiliar to her until Grant Magazine inquiries.

According to the Oregon state government website, there have already been several documented occasions of canine deaths and human illnesses due to the HCBs. Animals can be impacted by consuming the blooms or merely coming into contact with them. While the science behind human health effects from HCBs is ongoing, the OHA says, “Swallowing water can result in diarrhea, cramps, vomiting and dizziness,” and that “more severe reactions occur when large amounts of water are swallowed.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says more severe reactions could include such symptoms as joint pain, sore throat, severe headaches, gastrointestinal problems and electrolyte imbalances.

Raising awareness about the risks of the river where thousands of Portlanders spend their summers is important for the safety of the city’s residents; getting the people of Portland on board to solve the looming environmental issue is a crucial step towards making progress. By spending time on the river in places clear of HCBs, Portlanders can start to build relationships with the Willamette and realize the

importance of protecting it and its vulnerable inhabitants.

“It’s the world’s laziest river revolution. You can really make a difference simply by letting your friends know that the Willamette is something we should care about,” says Levenson.

Combining social cooperation with scientific research is the perfect cocktail for change. Levenson says that ultimately, “It is not an option to not try.”