“At first it was a little unbelievable, right? Here we are in the Soviet Union, our ‘archenemy.’ We were just wandering around. We were get-

ting pirozhki (a Russian meat pie),” says Joanna Gilson, 72. An ornate shawl complements her gray hair; to her right, on a worryingly sticky chair in a New Seasons Market dining area, rests a grocery bag filled with Soviet memorabilia. A large golden ring set with bright green gemstones glimmers from her folded hands.

“The threat was pretty far away, and pretty vague and nebulous for people our age,” she says. The “threat” was the fear of all-out war between the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) during the second half of the 20th century.

Gilson grew up in Portland, Oregon, and attended Grant High School; it was there that her interest in the Russian language burgeoned. Back then, Grant had a far more diverse array of languages than the three currently offered — American Sign Language, Japanese and Spanish.

After graduating from Grant in 1969, Gilson attended the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle, drawn by the university’s high national rank in Russian language programs. She went on to receive her master’s degree in Soviet History & Politics at UW’s Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies.

However, political polarization between the Soviet Union and the United States, as well as their respective political allies, created deep demonization of the other in both countries. “The (Soviets) were ‘the enemy’… I went there as a student because you couldn’t get into the Soviet Union otherwise,” says Gilson. “If you went with a student group — either on a tour or a study — you could get in because … we were young and we were, presumably, malleable in their eyes.”

Gilson traveled to the Soviet Union twice in order to immerse herself in the Russian language and environment. Though much of what was often associated with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe turned out to be true — fussy babushkas, dreary brezhnevka apartment buildings (concrete complexes built under the leadership of, and named after, Leonid Brezhnev) and tributes to formidable Soviet leaders everywhere — Gilson says informal interactions with Soviets teemed with curiosity about American life.

“Oh, my god, they just wanted to know everything about the United States … jeans! They wanted jeans and they wanted music,” she exclaims. “And they would say, ‘Wow, you’re just like a regular human being, aren’t you?’” She recounts how her group leader managed to steer them away from trouble by bribing the “swanky” Hotel National management with blue jeans and rock’n’roll albums after drunkenly breaking a lot of glassware. “It was illegal for Russians to buy that kind of stuff because it came in on the black market,” says Gilson. “It wasn’t necessarily illegal to possess that stuff.”

Gilson first traveled to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1971 through a Portland State University student group. The group traveled through Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) and Moscow in Russia, as well as what are now Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and the Crimean Peninsula before departing via the Turkish Bosphorus Strait. Besides the obvious ethnic diversity of the republics the group visited, Gilson took note of the contrast between Soviets across their respective nations.

“You could tell that the further you got south in the Soviet Union, the more relaxed people were, maybe more effusive as well,” says Gilson. “But we were warned, before we went to Georgia, if you’re in someone’s living room or kitchen … and there was a painting on the wall, and you said, ‘Wow, that’s really cool, I really like that,’ it was their custom to take it off the wall and to give it to you.”

When she was 27, Gilson returned to the Soviet Union through an Ohio State University program to study at the prestigious M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University for the fall-to-winter semester. “So I got to experience a winter in Russia,” she says, adding that her phone was, in fact, bugged, and that every student was required to check in with a keyholder. “As a foreigner, we couldn’t go, like, 25 kilometers outside of Moscow.”

Gilson never used any code words over the phone, as she was instructed to do when arranging to meet with others, and would constantly be followed by what she assumed were Russian secret service agents. “I made friends with a number of Muscovites while I was there, and spent a lot of time with them,” she says, “and we were off and on tailed by people. And my Russian friends would just laugh it off and say, ‘Yeah, it happens.’”

She was told to be “divinely indifferent” to anything that went wrong, such as food running out of stock by the time she got to the front of ration lines, as that was how Soviets went about life so as to not be constantly aggravated.

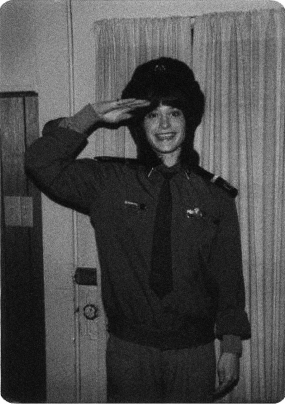

At the New Seasons, Gilson places three thick photo albums on the table, stocked with faded but neatly-arranged photos of Red Square and imposing posters of former Soviet heads of state Brezhnev and Vladimir Lenin. One of the photos shows Gilson dressed in a Soviet military costume, beaming under a black ushanka hat adorned with the hammer and sickle, the symbol of the Soviet communist party.

Other Soviet memorabilia includes a short story she wrote at the time in Russian. “You can see that I wasn’t exactly perfect (at Russian),” Gilson says, citing small corrections made on her writing in red pen. However, she spoke so well, and without any significant accent, that when introduced to other people by her Russian friends, they would say Gilson was a Lithuanian friend of theirs.

Beginning in the 1970s, Jewish emigrants (also referred to as “refuseniks” due to their difficulties immigrating to, most commonly, Palestine or the United States) were only permitted to leave the USSR in periodic waves. During her second trip, Gilson was asked by a Jewish family immigrating to the United States to smuggle the husband’s doctorate mathematics dissertation out of the country. As it was considered property of the state, he was unable to take it with him. Without his dissertation, the husband couldn’t offer proof of his qualifications in mathematics.

“I had an over-the-shoulder bag … and I stashed the dissertation (in) there,” says Gilson. “Every time you crossed a border, there would be border patrol with, what looked to me at that time, very fierce German shepherd dogs … And I was thinking, ‘Maybe I’m just gonna be a cute

little girl, and they’re not gonna bother me’ … That was the scariest part, actually.”

They didn’t bother her, and Gilson learned that the dissertation had made its way back to the family when a colleague of hers at UW’s Russian and Eastern European Studies department mentioned it in passing nearly two decades later.

From 1979 until 1995, when she moved back to Portland from Seattle, Gilson worked two jobs at UW before becoming the Director of Student Services for the Jackson School of International Studies. She says that having learned Russian, and becoming fluent in

the language, gave her a feeling of “wonder” that “still persists.” Her time spent visiting operas, ballets, waiting in lines for bread and walking around various Soviet cities allowed her to follow through with her aspirations of understanding another country, although she was left startled by Soviet indifference to despotism.

“There was the passivity in the face of authority and their deep belief in fate. The former was fed by cruel consequences to questioning authority and the latter led to sometimes reckless behavior and a culture of heavy drinking,” says Gilson. “Whether that was from living under sadistic and authoritarian regimes for millennia or from their deep history of religious beliefs during that time I don’t know, but it was

quite foreign to me.”

Despite the harsh antagonism between the United States and the Soviet Union, Gilson loved her visits behind the Iron Curtain.

“I had the time of my life,” she says, a twinkle in her eye.