Lights buzz and faint pop tunes waft over rows of shoppers as Grant senior Leo Butler stocks shelves at Fred Meyer. His work is interrupted by the approach of a man in ordinary clothing. However, this is no typical shopper. He’s on a mission — recruiting young, hardworking high school students to the United States Armed Forces. The badgeless recruiter asks Butler about joining the military. “I kind of signified that I didn’t want to join it multiple times,” says Butler, “He just kept pushing it and wouldn’t really stop.” Butler is only able to return to his work when the probing is cut short by his manager insisting the recruiter leave the store.

The military’s history of invasive recruiting tactics, as well as continued use of controversial and violent practices, has led to a distrust of the institution among Grant students. “I feel like you’re kind of just a number to them,” says Butler, “They act like they’re interested in you joining the military, but they’ll take anyone.”

In contrast, some say that this stigma might deter students for whom the military could be a good option. Russell Peterson enlisted straight out of high school, and is now a social studies teacher at Grant. He says his experience in the military was “one of the formative experiences that shaped (his) adulthood.” Peterson adds, “I think there’s a certain disdain for people who choose to go into the military relative to going to a four-year college. Whether that is real or imagined on my part, that’s just a perception I have.”

Peterson’s young enlistment age is not unique. In their 2020 “Demographics Report,” the U.S. Department of Defense reported that 40.6% of all military personnel were 25 years of age or younger. Only 20.3% were 26 to 30, the next largest age group.

The conflict around military recruitment at Grant is most prevalent during campus military visits. Organizations like the War Resisters League (WRL) set up their tables right next to the Armed Forces and hand out counter recruitment literature. “We also do it just to keep an eye on the military recruiters,” says John Grueschow, a draft resister during the Vietnam War, “They just push and push, just trying to get more and more leniency in terms of their recruitments.”

Butler says, “If someone has the right to come in and recruit, then I guess someone should have the right to protest it.”

Grueschow has been working to inform Portland high school students for 37 years. He moved to Portland in 1979 and began grassroots counter-recruitment in the few years following. His later affiliation with the international WRL gave more credibility to his school board petitioning, board meeting protesting and covert school visits. Through his continued work against military recruitment in Portland high schools, Grueschow has seen the lengths recruiters will go to appeal to students.

In the past, the military could show up whenever they wanted and for as long as they wanted. Grueschow says recruiters have even gone as far as to “walk around the buildings and talk to kids in restrooms.” Portland Public Schools (PPS) has a tumultuous history with military recruiters, something Grueschow has seen firsthand.

In 1985, the Pentagon’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy regarding gay and lesbian military personnel was deemed a violation of the district policy that prohibits any recruitment from agencies that discriminate based on race, gender or sexual orientation. After years of campaigning, Grueschow and his colleagues succeeded in banning the military from entering PPS high schools. However, former President George W. Bush’s 2002 No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) brought the recruiters back into schools under threat of loss of federal funding.

In 2015, under former President Barack Obama’s administration, NCLB was replaced with the Every Student Succeeds Act, which continued to require that “each local educational agency receiving assistance … shall provide, on a request made by military recruiters or an institution of higher education, access to secondary school students’ names, addresses, and telephone listings.”

However, Air Force Magazine says, “31 percent of US schools deny (recruiters) access in one way or another.”

PPS was especially unwilling to give up the fight against unregulated recruitment in schools. In their Administrative Directive “Recruiting Activities on Campus,” the district details the rules military recruiters must follow when on school sites. The directive includes strict prohibition of any unannounced or unidentified visits by recruiters, the causation of any disturbances of the educational environment, solicitation of any materials to students who have not approached recruiters or engagement in any “informal recruiting,” like eating lunch or having casual conversations with students.

Discrimination based on sexual orientation is not the only practice that has gotten the military into hot water. Recruiters have explicitly targeted lower-income students to such a degree that the practice has its own name. Grueschow is familiar with the term: “It’s called the poverty draft.”

The American Friends Service Committee lays it all out in their document, “The Poverty Draft.” According to the document, the Pentagon spends more than $2.5 billion every year in campaigns targeting “high-achieving low-income youth with commercials, video games, personal visits and slick brochures.”

Peterson says socioeconomic factors might affect students’ attitudes towards the military. He says, “Grant is a relatively affluent school and it’s predominantly white and it’s predominantly upper-middle class. And this part of Portland is the most liberal part of a left-leaning state. And all of those things I think contribute to the perception, attitude and values.”

The military’s continued assaults on disadvantaged youth are disproportionately affecting Black people.

Although poverty rates have been falling since 1959, Black people are still the poorest minority group in the nation: Census data shows that over 18% of Black people in America live in poverty.

The Department of the Army’s reporting says that Black Americans serve in the Army at a rate disproportionate to their population. In 2008, 21% of 18-39-year-old Black men were serving in the active-duty military while only 17% of them had high school diplomas, and 13% of Black men ages 25-54 were Army Officers while only 9% held college degrees.

The Marine Corps North Portland representative, Staff Sergeant David McCarter, is not concerned about PPS’ regulations. To him, it is a matter of quality over quantity. “I always try to make sure I have the best relationship with the staff at the school … If I’m not talking to the principal here, and the vice-principal, I have no relationship, then that’s really not helping me out and not helping the students out either.”

The military does offer some exclusive scholarships like the $180,000 Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps Scholarship (NROTC) that send enlistees directly to college. However, most people enlisting in the military for college benefits use the more general Post-9/11 GI Bill, which helps veterans pay for post-service school or job training.

Despite the potential benefits for enlistees, Grueschow’s stance on the matter remains clear: “I don’t think the military belongs in schools.”

“Military recruiters can say anything they want to a kid, they can make any promise they want to,” he says, “It says so right in the contract that you sign. Your whole list of things can be changed at any time.”

According to Section 9-b of the U.S. Armed Forces’ “Enlistment/Reenlistment Document,” Grueschow is right: “Laws and regulations that govern military personnel may change without notice to (the enlistee). Such changes may affect status, pay, allowances, benefits and responsibilities as a member of the Armed Forces regardless of the provisions of this enlistment/reenlistment document.”

The WRL wants to make sure students are not only getting information from the military, but that they are also making the most informed decisions possible regarding enlisting. Their “Do You Know Enough to Enlist?” pamphlet urges students not to sign any documents without having a trusted parent, guardian or teacher review them.

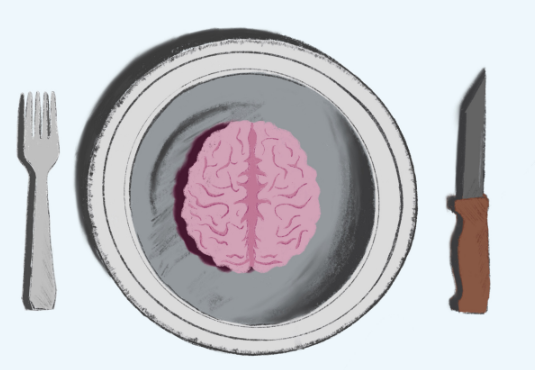

For those who enlist, benefits are not the only factors that need to be taken into account. A 2017 study by Hill & Ponton Disability Attorneys found 12.9% of veterans were diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), almost twice as many as the general U.S. population. The VA also estimated 4.26 million veterans received Disability Compensation benefits in 2015. “If you do three or four tours of duty, you’re pretty nuts,” says Grueschow, “It really affects you.”

The WRL says, “If your only source of information about Armed Forces enlistment is military recruiters, then you don’t know enough to make an informed choice.”

Although McCarter feels the military is great post-service preparation, organizations like the American Friends Service Committee and WRL believe many military-learned skills are not transferable to civilian life.

“A lot of people aren’t ready to go to college after they get out of the military,” says Grueschow, “There are other options.”

Some of the alternatives Grueschow and the WRL endorse are community college, apprenticeship programs, internships or on-the-job training. They also endorse Americorps, an organization serving alongside non-profit organizations to tackle the nation’s most pressing challenges.

However, the military can be beneficial for many.

It gave McCarter resources, financial stability for him and his family, a steady job for over ten years and the chance to travel all over Europe and Asia.

Peterson also valued his time in the Armed Forces. “You kind of romanticize things because you’re young and strong and beautiful,” he says.

For Peterson, rather than a way to go to college, the military was an escape from it. He felt unprepared for college and did not want to go to trade school. He wanted something interesting; he wanted a challenge. A month and a half after graduation, and only three months into his legal adulthood, Peterson went to boot camp.

He served in the Gulf War in 1990 and 1991, and spent a lot of time on a boat doing “big circles in the ocean.” After “a lot of boredom, punctuated by moments of excitement and terror,” some lifelong friends and minimal physical and mental damage, he got out.

Peterson thinks that in some places, enlisting is dismissed too quickly. He says, “Not a lot of students from Grant elect … to join the military and I think that also creates a misperception or misunderstanding of what it is and what it’s like.”

McCarter and Peterson both stress the importance of students’ confidence in their decisions before investing time and money in a profession they might not want. McCarter says, “You’re only gonna do the best you could do if it’s something that you want to do.”

Grant senior Kai Hayes looks forward to a future in the military. “I want to serve my country and protect my friends and family,” he says, “Also, it’s just the mental benefit and the values that you learned in the military that I think are beneficial.”

Hayes says that before enlisting, he made sure to do research outside of military websites and conversations with recruiters. He says “I feel like people should inform themselves before they go see a recruiter … because some recruiters may have a little bit of a bias or they’ll manipulate it because they have a quota to fill. Some don’t, some do.”

Hayes does feel, however, that the level of skepticism towards the military at Grant may be overreaching. “I’ve definitely noticed a lot of people saying that the military is a terrorist organization. I think that is really ignorant … because there’s a lot of really good people in the military. So I do think there is a bias.”

As this debate rages on, graduating Grant students make decisions that will forever change their lives and the lives of others.

To some, serving in the military can be a positive learning experience, and many enlistees return home unharmed. “I had many more positive experiences than negative ones,” Peterson says.

However, anti-war protesters urge consideration of the effects the U.S. military has beyond the safety of their personnel. According to a report by the Watson Institute of International & Public Affairs at Brown University in the near 20 years of the Afghanistan War, more than 241,000 people were killed, including over 7,000 U.S. service members and more than 71,000 Afghani civilians as of April 2021.

“War doesn’t work very well anymore, and it never did,” says Grueschow, “I mean, it really changes you.”♦