It is six o’clock in the morning when Grant senior Seamus Brindley’s alarm sounds. His phone, blaring an obnoxious ringtone, is purposely placed just out of reach, forcing him to stand up and get out of bed to stop the sound. Once his room returns to quiet, Brindley walks over to the east wall of his room. Brindley starts his morning by offering water to the Buddha at his altar, a ritual he repeats daily.

Brindley proceeds to eat breakfast and prepare for the day until he feels fully awake and ready to transition to his morning Buddhist practice. “Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo.

Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo. Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo,” chants Brindley, sitting on his knees, his prayer beads interwoven between his folded hands. This specific chant embodies the core teachings of the Lotus Sutra, the last lessons of the Buddha.

Following this prayer, he places a piece of paper into his mouth to avoid breathing on the Gohonzon, a scroll used to aid practitioners of Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism that he keeps in his altar. Brindley opens the scroll and then lights a candle and incense.

Traditionally, the morning prayer is initiated by a turn toward the east, to pray facing the sun. Since Brindley’s altar is on the east wall of his room, he shifts very slightly to the right to mimic this tradition.

He chants “Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo” three more times, following with a prayer to the forces who control the sun, Shoten Zenjin, and closes by reciting different chapters of the Sutra. Finishing the entirety of his morning ritual, Brindley chants “Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo” once again. This time, he repeats the chant as many times as he feels necessary, allowing him to enter the day feeling relaxed and prepared.

“It’s just important to me to, you know, be reminded every morning what I’m really focusing on … ‘cause otherwise it’s really easy to get sort of swept away by stuff, you know, problems that come up in day-to-day life,” says Brindley. “It just helps me to remember that those don’t really matter as much because I have this practice.”

Brindley was first introduced to Buddhism during the winter of his junior year. When his uncle invited him to participate in a group Buddhism practice, Brindley was hesitant, worried that the teachings of the practice were arrogant. However, deep down, he felt a strong need to attend, sensing the practice’s importance in his life.

After around six months of practicing Buddhism, Brindley developed a connection with the religion. With this newfound understanding of the practice, he made a life-changing decision: to dedicate himself to Buddhism.

“It’s something that I never expected I would be doing or would be a part of my life, but it’s really changed how I see myself and the world,” says Brindley.

As a child, Brindley often felt like he had a sort of “existential angst,” questioning the reason behind his existence. However, after finding Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism, he began to partake in self-reflection.

“Now, I look at myself and everything around me, and I understand that it is all me. Everything is a reflection of yourself and not all of it is very pretty,” says Brindley. “I understand that it is just karma and I just have to take that and do what I can with it.”

This new perspective has led Brindley to become more at peace with not only himself as a person, but with his life as a whole. “Whatever’s going on, as long as I’m still practicing, there’s this like, happiness,” he says. “So that, even if I’m having a harder day or whatever, I can just ride the up and down.”

However, when Brindley was born in Chicago, Ill., on April 15, 2001 to Mary Brigid Brindley and Kevin Brindley as a girl, he did not have that stable foundation to fall back on. From a young age, he would often question his own existence.

At the age of 4, Seamus Brindley and his family moved to Minneapolis, Minn., where he grew up living on Cedar Lake. Brindley spent his free time playing Pokemon with his brother and attempting to imitate what his mother would sometimes play on the piano in their house. When he was about 5, Seamus begged his mother to sign him up for piano lessons, and he began to

play piano regularly.

According to Brindley’s mother, Mary Brigid Brindley, he enjoyed “just running around the neighborhood when he was younger and playing with kids. He was a pretty happy-go-lucky kinda guy.”

Brindley attended Kenwood Elementary school in Minneapolis. Although Brindley identified as female at this time, many of his classmates were confused when he used the girls’ bathroom.

“Growing up, I was always much more masculine presenting,” says Brindley. “That confused a lot of kids when I was little, and there was some bullying going on because the whole bathroom situation was so confusing because everyone thought I was a boy and would freak out when I was in the girls’ bathroom.”

Then, when Brindley began attending Susan B. Anthony Middle School, he joined the school’s LGBTQ+ club per his mother’s recommendation. While attending these club meetings, Brindley began to learn about the terminology and what his sexuality and gender meant.

“It was sort of at that age when it sort of clicked that it was more of a gender thing and a relationship with my body than just who I liked,” says Brindley. Despite this revelation, Brindley continued to struggle with his body image and gender. “I was definitely very uncomfortable and just felt really trapped,” he says.

Brindley eventually came out as transgender to his mother, and then to his father, a few months after joining his school’s LGBTQ+ club. Coming out was a relief for Brindley; “It felt great to have it not be hidden,” he says.

However, after coming out, Brindley still struggled with questions regarding his body and who he was. This uncertainty negatively impacted his mental health for the rest of middle school. “I didn’t feel right in my own skin,” says Brindley.

Despite his struggles with his gender during this time, Brindley’s classmates were accepting of his gender identity.

Throughout his years in middle school, Brindley continued playing piano. He also began taking Japanese and developed a love for the Japanese language and culture.

Following his time at Susan B. Anthony Middle School, Brindley applied to a suburban high school, wanting to surround himself with people who had not known him from his earlier years in school. “I was just kind of tired of explaining the whole process to people,” says Brindley. “I was just sick of the people I grew up with.”

During his time at Minnetonka High School, Brindley had a different yet exciting experience. “I made a lot of friends really quickly, which was weird for me,” says Brindley, who only had a few close friends throughout middle school.

But after his sophomore year, Brindley and his family moved to Portland, Ore., where his father was attempting to start a business.

After leaving all of his friends behind in Minnesota, Brindley began to look for a new companion, specifically to aid with his mental health. His searches led him to his service dog, Fender, a black poodle who was born on the same day of the 2017 solar eclipse. “He definitely helps me, he’s very responsive to (me) when I need attention from him,” says Brindley. Similar to practicing Buddhism, Fender helps Brindley feel grounded.

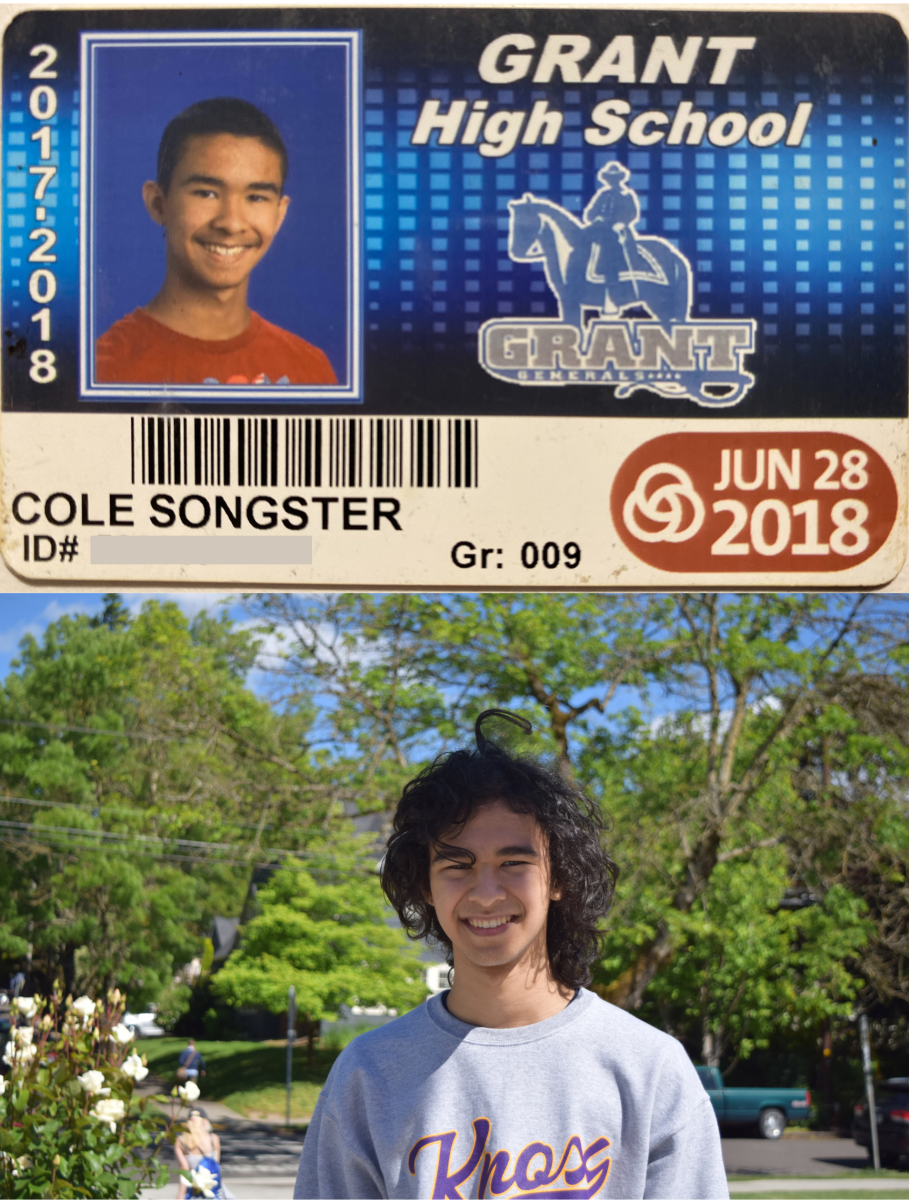

For his junior year, Brindley began attending Grant High School. At Grant, he enrolled in Japanese classes and continued his education around the Japanese language and culture.

However, Brindley quickly encountered a difficult social scene at Grant. He found that almost everyone he talked to was friendly, but he says it seemed like everyone had already established their friends, and it was challenging to integrate into others’ friend groups.

Brindley says that this struggle could result from his difficulty to express himself at times. “I feel like it’s so difficult for me to really communicate what I mean through just language,” says Brindley.

As well as struggling to connect with people at school, Brindley was also struggling with anxiety, having a tough time understanding the purpose of life.

However, when his uncle first asked him to come to a Buddhism practice during the winter of 2018, Brindley’s life was changed.

At the time when he was asked, Brindley’s heart began to race. He felt as if his body’s response to this invitation was a sign encouraging him to attend the group practice. “I sort of knew that I had to go … something in me was telling me that … it was important for me to go,” Brindley says. Despite this feeling urging him to go, part of Brindley remained reluctant and skeptical due to his family’s negative perceptions of religion in general.

Brindley was raised in an atheist family and had never really thought about religion as beneficial. When he first looked into the sayings and teachings of Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism, he was dubious of its message.

“It does say that other religions or other practices are either incomplete or just incorrect, and that they’re causing people to suffer and so to me that … sounded so arrogant and closed-minded,” says Brindley. After further study, Brindley’s understanding of these views deepened. “I can see that there’s logic and reason behind that.”

During the first six months of experimenting with the Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism practice, Brindley felt that he had connected with a community, which he had struggled to find in high school. “I really felt like this community was different in some way. That there was this … mutual understanding between everyone there, and just like a lot of love,” says Brindley.

Brindley’s mother has noticed that his practice of Buddhism has affected every aspect of his life. “Buddhism is really carried forward through everything,” says Mary Brigid Brindley. “I think that he’s become more mature through it, so that he can approach those things sort of in a little bit different way than he used to.”

Seamus Brindley agrees. “I feel like it sort of establishes a sort of baseline in your life of just okayness … So no matter what is going on around me or what I’m experiencing in my body or what mood I’m in on a certain day … everything is fine, you know. It’s sort of like happiness that is just always there,” he says.

Moreover, Brindley’s practice of Buddhism has helped him with his relationship with his body and its relation to his gender. “I mean, I knew before that what someone’s body looks like isn’t what’s important, you know, but I still couldn’t shake whatever my attachment was to my body image out of my mind,” Brindley says about struggling with his gender. “Practicing … (Buddhism) has definitely helped me to do that.”

His mother has also noticed these benefits, recalling that “if he gets upset, he’ll go and chant for a little while and just feel a little more relaxed about the topic and be able to take a look at it,” says Mary Brigid Brindley.

To close the day, Seamus Brindley repeats his prayer practice: kneeling, chanting “Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo” and reading the same prayers. He finds that between these two regular practices and larger group practices, Buddhism plays an incredibly important role in who he is as a person. “It’s just providing really great opportunities for me to grow and just feel good,” says Brindley.

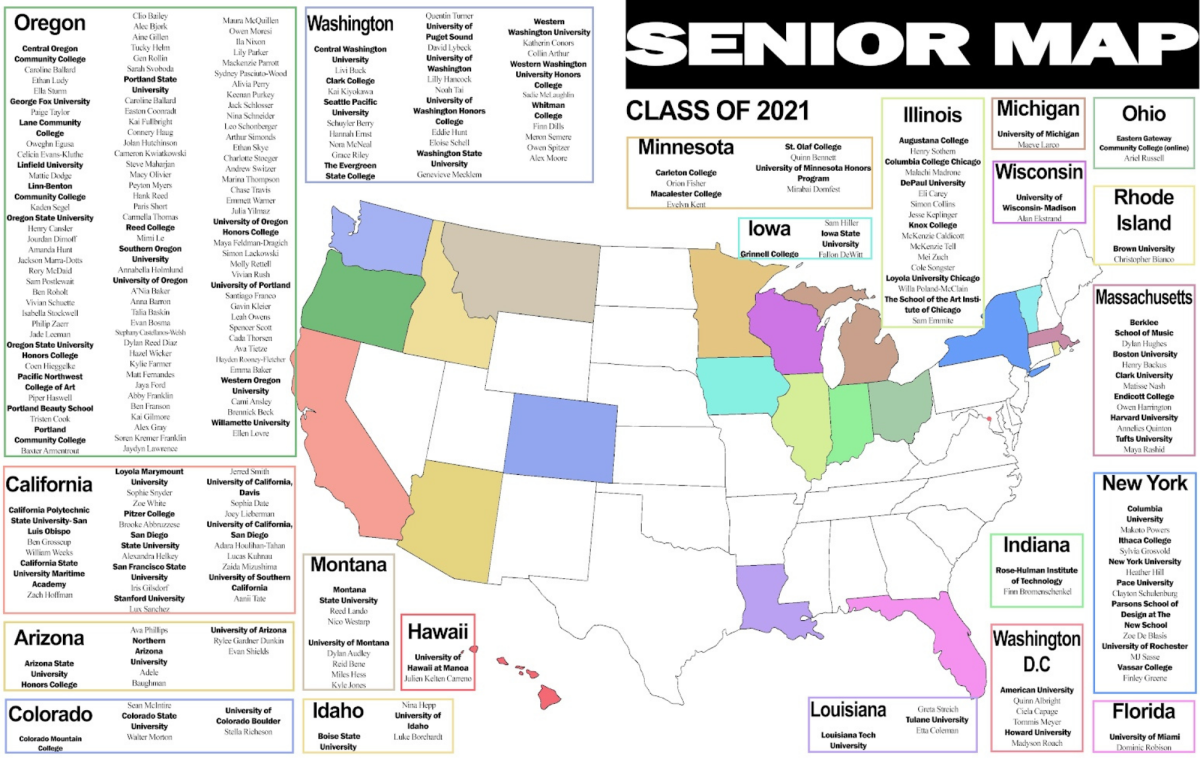

Following high school, Brindley plans to attend Lewis and Clark College to study Japanese and play the piano. “I think it’s … another one of those grounding things. I mean it’s something that he gets frustrated when he can’t do it the way he wants to, but then he just works at it and works at it and it’s just beautiful,” says Mary Brigid Brindley of her son’s piano playing.

Additionally, Seamus Brindley’s love and dedication for Japanese and Nichiren Shoshu

Buddhism have inspired his hopes to travel to Japan in the future, to visit the head temple of Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism. This visit, known as the Tozan, is a pilgrimage to the True Buddha.

Although he discovered his love for Japanese when he began learning it in middle school, he thinks that the fact that Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism originated in Japan is not a coincidence, considering his belief that Buddhism creates a genuine connection between every aspect of his life.

“I think that would be really a powerful experience,” says Brindley. “I’ve heard from a lot of people that after they go on their first Tozan, that there’s definitely, like something changes, you know with their practice. It gets a lot stronger.”

Brindley has an optimistic view of his future and what it may entail as he continues his practice of Buddhism. “I mean (practicing is) more important to me than anything,” he says. “As long as I’m still practicing … I know that if I’m doing that, then whatever is happening is supposed to be happening.”