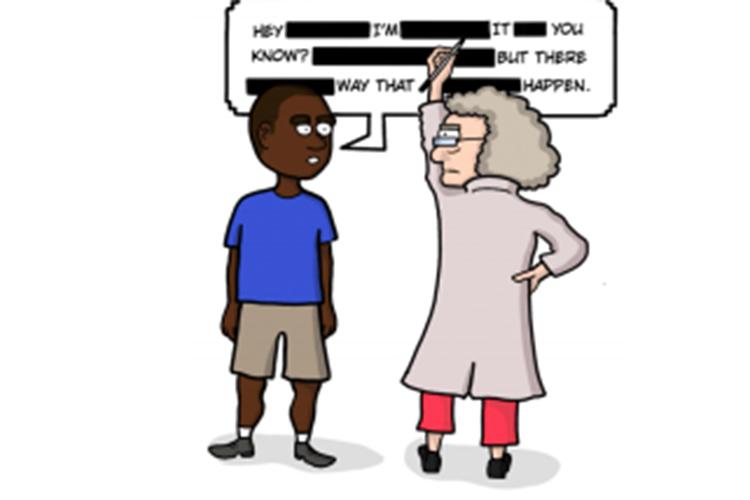

Senior Adam Clavon recalls an essay he wrote freshman year about the history of racism in the United States in which he used the N-word. As his teacher slid his work face down across the desk, a few red markings bled through the paper and caught his eye. Clavon, who is Black, flipped his assignment over in confusion and was surprised by his grade. He quickly scanned the essay to find the issue; a comment on the page read, “points taken for profanity.”

Clavon’s teacher had circled the N-word, which Clavon had used in his essay to describe the course of historical events from his perspective as a Black person.

There was no further conversation between Clavon and his teacher about his use of the word.

When the conversation around recognizing African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) was introduced by the Oakland School Board in 1996, the Black dialect was seen as a primitive language used by the uneducated. Brent Staples of the New York Times called it “broken, inner-city English” and “urban slang.” This perception created an expectation of lower levels of achievement and aptitude from students who used AAVE. A bias against this feature of Black culture is still perpetuated today in Portland Public Schools, a district in which only one out of eight racial discrimination investigations resolved in the past three years resulted in any tangible change.

In order to correct the misconception that people who speak AAVE are intellectually inferior, there must be an understanding between teachers and their Black students about the history of AAVE and the cultural importance of the dialect. “We have some control over how we speak, but there’s a way that we speak that we feel is natural and it often comes with how we were raised,” says Grant English teacher, Jonathan Carr.

According to Dr. Darrell Millner, a retired Black Studies professor from Portland State University, modern-day AAVE formed when African slaves were denied access to formal education, making it impossible to learn Standard American English. Slaves absorbed bits of English as part of the acculturation process, while simultaneously adopting their own grammar and pronunciation rules. AAVE was also influenced by words and speech patterns from their native African languages. “Black culture is a culture in which individuals are knowledgeable in a variety of languages and a variety of dialects,” says Dr. Millner.

In 1996, the Oakland School Board approved a resolution recognizing AAVE as the primary language of Black students. At the time, 53 percent of students were Black, but they received 80 percent of suspensions and had an average grade point average of 1.8 out of four, according to the Senate Special Hearing on Ebonics.

Though the resolution was intended to prevent the isolation of Black students, the general public was immediately opposed to acknowledging the unique dialect.

In Jan. 1997, AAVE was officially categorized as a valid dialect with distinct rules of grammar and punctuation following an annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America. Because of this, using the word “slang” to describe AAVE – as many of the Oakland resolution critics did – is incorrect, since slang refers only to a small set of modern words. In the United States, Black people have been speaking in AAVE since the beginning of slavery.

But when students use AAVE in an academic setting, they are often viewed as less articulate. “The way that we talk, I think (teachers) would assume that I might not go to college,” says junior Michael Preston, who is Black. “They assume that I was raised in the hood, that I’m not really school-trained.”

Clavon agrees. “I’m pretty sure a couple of my teachers have thought I’m gang-related … just because of the way I talk and act in class,” he says.

Racial microaggressions, which Dr. Millner says are often based on dialect discrimination, also manifest in the form of disproportionate punishment of Black students. While only making up 10 percent of the student population at Grant, Black students account for 50 percent of expulsions and 42 percent of suspensions, according to ProPublica database.

In order to provide Black students an equal opportunity to succeed, AAVE should be acknowledged as a valid dialect.

It is important to have an open dialogue between teachers and Black students about the use of AAVE because some teachers may not understand a Black student’s position. “I don’t think (teachers) should tell kids that what they are saying is wrong or not the correct way to say it,” says Clavon.

“I know the way I speak, I know the way I articulate myself and I know it doesn’t change anything,” he says. “It only changes your emotions that are clouded by whatever prejudice you have because of the way I talk.”