According to the United States Department of Justice, around a quarter of undergraduate females experience sexual assault during their time in college. Sexual assault is a prevalent issue on college campuses, and the recently proposed changes from the Department of Education as to how colleges handle sexual assault need to be carefully understood.

On November 16 of this year, U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos released rules mandating colleges to follow a new set of regulations regarding sexual assault on college campuses. These rules would make the process of reporting more difficult for victims, narrow the definition of sexual assault, limit investigations to formal complaints, require assaults to have happened on campus in order to be investigated and allow the accused to cross-examine alleged victims through a third party. Students need to be made aware of these changes in sexual assault policies on campuses and how they will directly affect them.

“When talking to colleges or looking for colleges, the first thing I actually do ask for are about their policies surrounding sexual assault,” says Kelly Schooler, a junior at Grant. For Schooler, a school’s policies are a large component in choosing a college. However, for the majority of students at Grant, this is an overlooked element because there is little emphasis on policies like these in high school. These policies directly affect any Grant student going to college as they strip protections for victims of sexual assault. With 20 to 25 percent of college women being victims of “forced sex” according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC), these rulings will have direct effects on students heading to college. High school students need counselors and parents to help bring this issue forward and emphasize its importance.

Unfortunately, with the newly proposed regulations, colleges would have little control over their individual sexual assault policies. Still, there are some rules the Department of Education does not state as mandatory, including what standard of evidence should be used in conduct hearings. Though they are only elements of a college’s policies, the direction a college takes in interpreting discretionary, or non-mandatory rules plays a large part in how a college deals with sexual assault. These regulations, especially discretionary rules, need to be emphasized when students are looking at colleges.

According to the NSVRC, rape is the least reported crime with 63 percent going unreported.

These new policies would likely reduce the already small pool of sexual assault victims who report. It is a hard enough task to summon the courage and put a traumatic experience on full display to be picked at and undermined. Imagine what would happen under DeVos’s new restrictions.

With these new policies, reporting sexual assault will only become more complex and strenuous. “One of my biggest concerns is that it will create additional barriers to people reporting,” says Julie Caron, the Title IX coordinator at Portland State University.

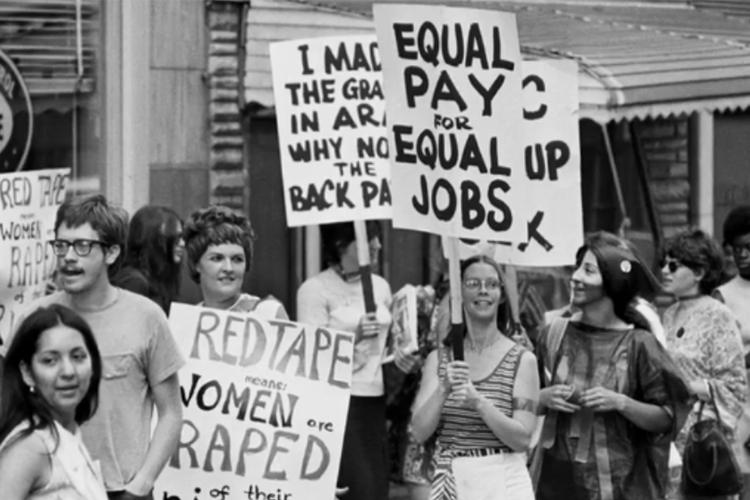

Colleges have been held accountable by Title IX — a federal civil rights law — since 1972, for cases of sexual assault. Title IX prohibits sex discrimination in federally-funded education programs. Since being implemented into the legal system, Title IX has been continually modified. One of the most recent improvements, the “Dear Colleague” letter, came under President Barack Obama’s administration. The letter reminded schools of their obligation to uphold Title IX and threatened to withhold federal funding if a college did not comply. “What I saw from the Obama administration in 2011, they issued new guidelines,” says Caron. “And it wasn’t that they were asking institutions to do something new, but they were reinforcing that it needs to be addressed between student and student. And helping to make it so students are comfortable with being able to report.”

But DeVos’s proposed regulations would move in the opposite direction, destroying the progress the country has made. These changes would shift the definition of sexual harassment and narrow it to “unwelcome conduct on the basis of sex that is so severe, pervasive and objectively offensive that it denies a person access to the school’s education program or activity.”

Under Obama, sexual harassment was defined as “unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature.” With these changes, situations which would have previously been considered sexual assault will no longer be considered as such legally.

DeVos is at the forefront of these changes. She aims to protect the small percentage of people falsely accused, discounting the vast majority of legitimate cases. According to the NSVRC, the rate of false reporting is between two and 10 percent, but there is still the belief that false accusations regarding rape are much more frequent. The proposed rules continue to fuel that myth.

But before these rules can go into effect, there is a public comment period of 60 days.

Students, educators and parents need to write letters to the Department of Education urging that the Trump administration not enact these policies which will intensify the process to achieving justice for victims, as well as create a less safe space for students pursuing their education.

Grant counselors need to bring awareness to this aspect of choosing colleges when they advise students. “I know that counselors do go talk to their students about college, or they have a college checkup, so asking students, ‘Oh, have you thought about (sexual assault policies) being a factor to choosing your schools?’ or, ‘You should consider this,’” says Schooler. “And I think we should actually reach out to students … (and) educate students on why is it so crucial or important to know about this and to be aware in their decision.”