Two years ago, then-sophomore Luke Heinrich and his teammates were getting ready for their varsity football practice in a Grant locker room when the room went pitch-black. Chaos ensued in the few moments before some of his teammates were wrestled to the ground by shadowy figures. Panicked, some of the players hid in the drying room, where the faintest bit of light was visible. Heinrich felt uneasy.

The perpetrators were Heinrich’s upperclassmen teammates. Despite being pushed around in the dark, the players brushed the hazing off as a joke. Heinrich felt pressured to do the same. “Everyone else was like, ‘Oh, I’m okay with this,’ so I was just like, ‘Okay, I guess we’re all okay with this,’” Heinrich says. “I wasn’t really sure what was going on, so it was a little scary, but I think I kind of just laughed it off like it was nothing.”

Heinrich says that situations like these were not one-time occurrences. In his experience, upperclassmen often “messed around” with the underclassmen, showing off their masculinity and taking advantage of their strength. “Some of the seniors were like, a little too aggressive, and like, physical they … would wrestle but like, the freshman and sophomores couldn’t handle that … that can be rough if you’re being held down and you can’t get up by a larger person,” Heinrich explains.

This is not the only example of toxic masculinity Heinrich has seen within sports. After a heartbreaking defeat at one of his final Portland Interscholastic League games this year, a sophomore teammate chose to mock Heinrich and some of his fellow seniors for being emotional. “I was crying because I’d played four years of football with my good friends now,” Heinrich says. “It was just, like, one of my last experiences with the game, so I was just emotional, so I just let it out.” According to Heinrich, the teammate ridiculed them, saying that crying wasn’t something that football players do. Many people consider “strength” and “toughness” to be masculine traits, while associating sadness and vulnerability with being non-masculine.

The idea that to be strong, one cannot express one’s emotions is a misinterpretation of what strength should look like. Dr. Miriam Abelson, professor of Women’s and Gender Studies at Portland State University, says, “Team environments can have a particular culture associated with them that is about, you know, being tough, about engaging in violence … a particular culture of proving oneself, and proving that one is tough and strong.”

Toxic masculinity culture is not specific to athletics. According to Abelson, it is everywhere, rooted in our society and our behaviors, and its consequences are many. Abelson defines toxic masculinity as “performances of masculinity that sort of reinforce a toxic environment for all people … masculinities that reinforce misogyny, and also masculinity that reinforces hierarchies among men and boys.”

The Grant community is considered to be very progressive, with student activists organizing gun control rallies, race discussions and various clubs focused on youth empowerment. But people often overlook the full impact of toxic masculinity. Dr. Kathleen Elliott of the University of Wisconsin – Whitewater says, “(Little examination of masculinity) allows … masculinity based on simplified norms and understandings of traditionally masculine characteristics such as violence, physical strength, suppression of emotion and devaluation of women … to flourish unfettered.”

“It totally happens,” Grant teacher Scott Blevins says about toxic masculinity. “Like, it is the world that we live in, if it is happening in the wider world of Portland, how can it not be happening (at Grant)? It’s the subtle stuff, comments about people’s bodies, comments about clothes. You know, just like little barbs like that.”

These comments, although seemingly inconsequential, can have a major impact on boys throughout their adolescence. For Heinrich, comments on his physique altered his perception of what it means to “be a man.” In his childhood, Heinrich’s father and his father’s friends would make remarks on his body, saying that he had “noodle arms,” that were “thin like spaghetti.” They would often tell him that he needed to work out more and start lifting weights.

“It definitely affected my confidence. I felt like I wasn’t a strong kid,” Heinrich says. “They just kind of put it in my head … when I was in freshman year, eighth grade, my mindset was like, ‘I have to be as big as my dad someday, as much of a man.’”

Media exposure on the malleable psyches of children is another way that children internalize the more negative expectations of masculinity. “I think that they are part of kind of messages that people see, so when we only see particular kinds of representations of masculinity, then that sort of limits the images that people have to kind of live up to,” says Abelson.

Many forms of media designed to appeal to children show only this harmful portrayal of masculinity. These lessons cause children to see this as the “ideal” form of masculinity.

Children that grow up watching aggressive and violent characters may try to emulate them by expressing the same patterns.

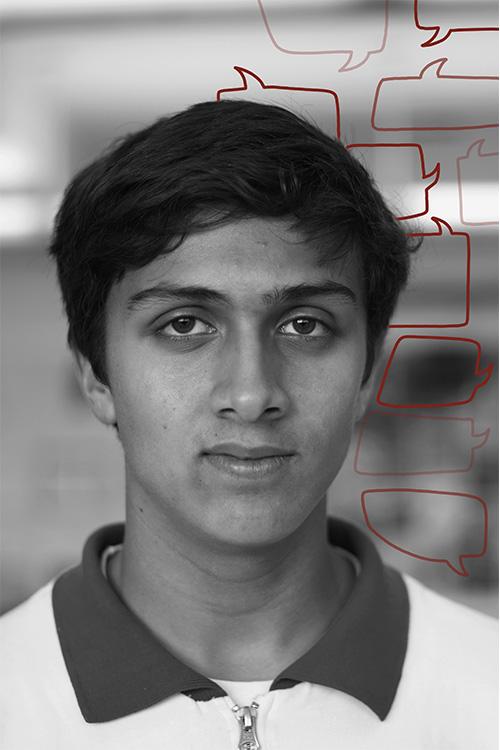

Junior Zak Yudhishthu understands the struggle of expressing emotions. Yudhishthu feels like he cannot be open about his feelings with his social circle.“My own group of guy friends … there’s definitely like this sense of masculinity where it’s like a lot of the time you feel like … it’s really uncomfortable with certain people to be like vulnerable or like share your own personal experiences because like it’s not masculine to be like talking about your own sadness or hurt,” he says. Though Yudhishthu says that he loves spending time with these friends, he avoids seeking emotional help from them.

Yudhishthu’s experiences with his friend group are not uncommon for males. According to James Mahalik, PhD, a psychologist and masculinity researcher at Boston College, men are less likely than women to seek help from a mental health professional. This is even when they acknowledge that they have serious problems pertaining to their mental health.

Similarly, in a 2016 study by the American Psychological Association, it is mentioned that “men who endorse greater adherence to traditionally masculine norms may ‘mask’ depressive symptoms. This masking can manifest in a range of externalized behaviors not typically assessed for in depression diagnosis.” The study states that these behaviors include expressing anger instead of sadness, turning to drugs and alcohol for self-medication and suppressing emotion.

Junior Kira Wilson’s life has been particularly shaped by toxic masculinity; her father had a troubled childhood, and suffers from a variety of problems as an adult. As a result of his struggles with alcoholism, Wilson’s father has not been a constant parental figure in her life. “I think that he really doesn’t want to talk about his emotions and he’s like made that into such a big deal for him, he will, like, not talk about his emotions at all,” Wilson says. “He’s afraid to admit weakness and get help.”

She remembers one particular time in which her father’s inability to verbally express his emotions worsened their relationship. On Thanksgiving of 2017, Wilson stopped by her father’s house after a long day of family gatherings. She says that she was feeling overwhelmed when her father pulled her in for a hug. Despite Wilson’s assertion that “she needed a second to breathe,” her father refused her request and hugged her anyway. She felt anxious and uncomfortable as her father escorted her inside and turned on a movie without talking to her or her siblings.

This was frustrating for Wilson. According to her, this was the first time he had seen her in three months, yet in the rare time he got to spend with Wilson and her siblings, her father did not bother trying to make conversation with any of them. After a while, she decided to ask her mother to pick her up since her father was not going to converse with her.

But after saying she wanted to leave, Wilson was met by her father’s anger. “He was like, ‘You’ve been here for an hour,’ and I was like, ‘Yeah, but we’re just watching a movie,’ and he was like, ‘Yeah, but we’re watching it together,’… He didn’t feel comfortable telling me that he cared.’”

For Wilson, this inability to communicate has been a major strain on their relationship. Wilson says, “If he wasn’t so insecure, in like appearing masculine and strong, that he’d be able to admit his weaknesses … our relationship would be a lot more healthy, but he doesn’t want to admit that he did something wrong.”

Wilson is not the only one with a father who struggles to discuss emotions. Heinrich says that he believes his father tries to hold in his emotions because he would be seen as “less of a man” if his kids or family saw him cry. For this reason, Heinrich sees his father as being more short-tempered because of the bottled-up emotion that he needs to release.

Heinrich sees toxic masculinity in other authority figures in his life as well. He says he has noticed coaches and peers enforcing masculine standards in harmful ways on the football field. Earlier this year, a teammate cried out in pain after receiving an injury on the field. On a different occasion, when another one of Heinrich’s teammates suffered a similar injury, the injured teammate refused to shed a tear. Later, during a team meeting, the coaches congratulated the dry-eyed player by giving him an award for “toughness.”

“Sports can be a really good place to learn things like teamwork, and learn, you know, how to work with other people. And that the negative parts of it, of this toxic masculinity, also becomes something that sort of spills out there,” says Abelson.

The constant stress that comes with feeling the need to conform to the standards of toxic masculinity, such as prioritizing the expression of strength while suppressing signs of weakness, follows males their entire lives. Sports have the ability to teach youth many valuable life lessons and skills, but if the competitive environment becomes toxic, the consequences can be extremely harmful. “On the football field, (my teammates are) just trying to be like as less emotional as they can be,” Heinrich explains. “Personally after my senior night, when I lost to Lincoln, I cried because it was sad … and I think there were like a few seniors who didn’t cry … that’s what (the coaches) like to see, they like to see less emotion, just more physical strength and toughness.” If athletes are forced to bottle up their emotions while on the field, it may become difficult for them to express those emotions off of the field.

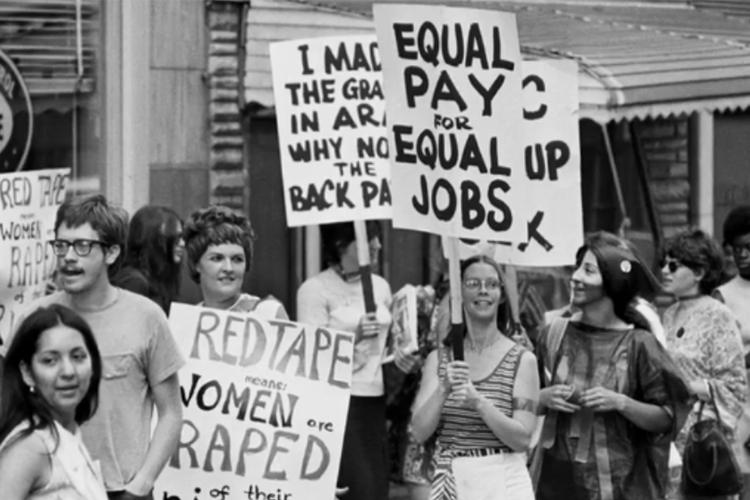

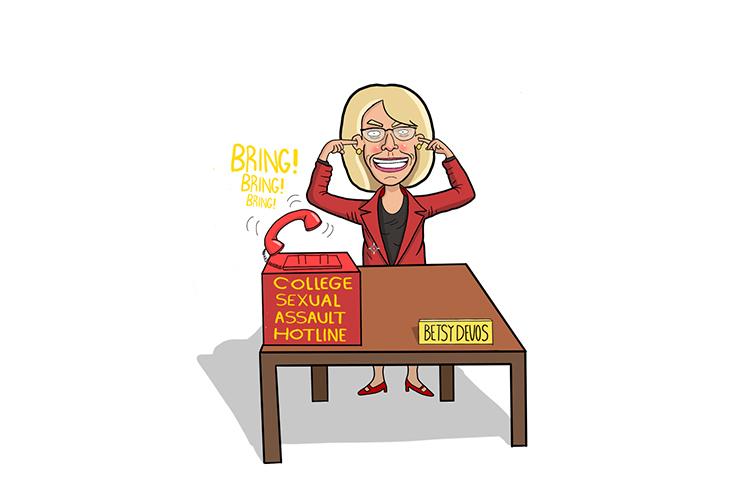

Toxic masculinity has manifested at Grant, and in our larger society. The effects are often small enough that, individually, they go undetected. It isn’t until they build up over a long period of time that they become recognized as a part of a larger problem. According to data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program, 99.1 percent of rapes are committed by males. This is a result of the culture that ignores the events that cause sexual assault.

The current #MeToo and Time’s Up movements have brought national attention to sexual assault, campaigning for women’s rights and exposing perpetrators. This progressive national atmosphere is also shedding new light on the many connections between sexual assault and toxic masculinity. “When one group of humans is not allowed to express them (selves then) a couple things happen, things get bottled up, and that stops people from being able to work through their feelings,” Abelson remarks. “That leads to a lack of ability to be able to handle things like anger and frustration.” The need to prove oneself physically could lead a male to attempt to force a partner to do something they don’t want to do. “(Boys are) being given a message that they are entitled to things like attention from women and girls or access to their bodies,” Abelson says.

Another aspect of the problem is the culture of competition between male-identifying friends. Heinrich recalls conversations in which his friends would try to outboast each other with sexual accomplishments. “They’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, I’ve done more than you.’ And the other one’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, but I’ve done this and this,’” Heinrich says. “It’s just always a competition to see who’s the best, or on top.”

Yudhishthu also experiences the “braggadocious” nature around sexual relations, especially between his soccer teammates. According to Yudhishthu, questions such as, “How come you haven’t done this yet?,” referring to a sexual activity, are common. Yudhishthu says talking about sex as a specific measure of a relationship is inaccurate and harmful, especially for boys and men that feel like their sexual experiences are insufficient. This in turn can lead to overcompensation on the man’s part in the form of unwanted sexual advances.

To address the problems around sexual assault, the problem of toxic masculinity must be addressed first. Otherwise, the cycle of toxic masculinity and sexual abuse will continue.

Heinrich is taking steps to avoid becoming another product of the cycle. “For me, I feel like … I’m not afraid to be who I am in front of everybody else. I’m not afraid to show my emotions or be open. I just don’t find myself with … the same personality traits that I see in my dad,” he says. Heinrich’s ability to recognize the existence of toxic masculinity and not fall into its trap sets a potential precedent for others. “If you’re comfortable with who you are, if you’re able to live your life and, you know, enjoy yourself, I feel like, yeah, you’re a man. You can just be you.”