Content warning: This story contains details about sexual assault.

Due to the sensitive nature of the story, some student sources have been made anonymous.

Names of sources who wished to remain anonymous have been replaced with letters for clarity.

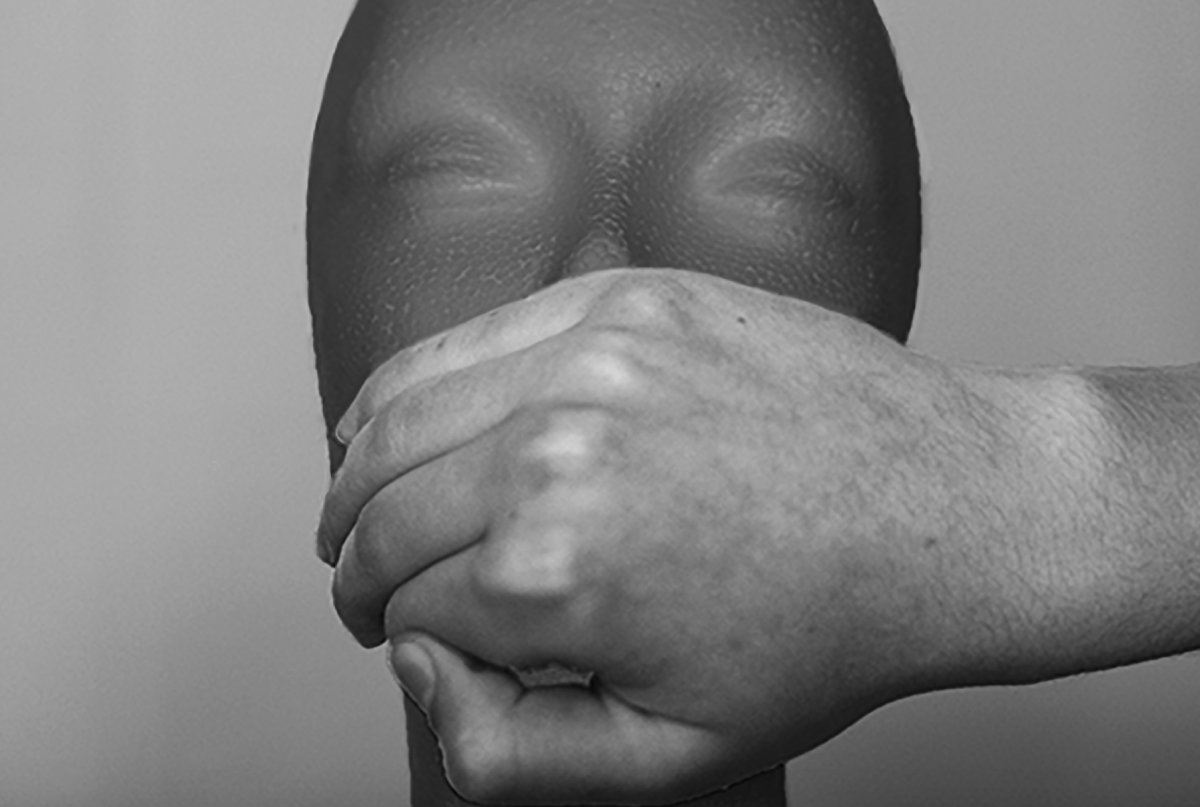

D was watching a movie with their friend, M, when M began pressing their body up against D and trying to kiss them. Feeling uncomfortable, D began thinking of excuses to get out of the situation, saying things such as, “I feel weird with your mom upstairs” and “I think my dad wants me home soon.” However, without an explicit “no”, M continued. “I never really said ‘no’ but I said things that I feel like made it seem like I wasn’t 100 percent comfortable in the situation,” says D. “But the person still proceeded to pressure me and then do sexual things.”

D stood up to leave, but M pushed them against the wall and continued attempting to kiss them. D pushed M away and left, confused about what had transpired. “After it happened I had some of my own questions like, ‘Was I saying enough? Is it valid for me to feel this way?’” says D.

Many students at Grant High School, when asked for their personal definitions of consent, expressed similar ideas. Some mentioned Planned Parenthood’s consent acronym, “FRIES” — freely-given, reversible, informed, enthusiastic and specific. Others classified consent as “permission” or an “enthusiastic yes.” Students seem to have a substantial idea of what consent means, but when it comes to specific situations, there appears to be a lack of a nuanced understanding.

“It’s just a very seemingly kind of simple concept, but once we actually look at it, it gets more complicated,” says Grant sophomore MJ Sasse.

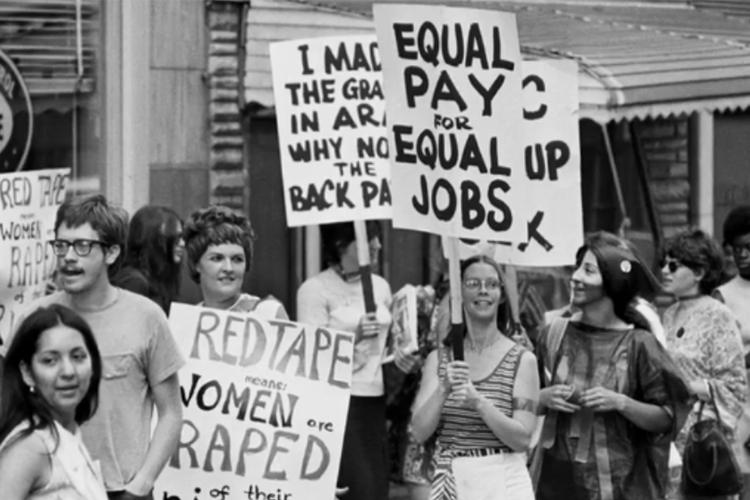

This problem is not limited to Grant students. In a 2007 survey by the Department of Justice, 35 percent of sexual assault victims stated their reasoning for not reporting the assault as “unclear that it was a crime or that harm was intended.”

Many kids are having their first sexual encounters in high school. According to New York Times, 42 percent of students aged 15-19 have had sex. “When (conversations are) about sex, I’ve had times where people don’t talk about (consent),” says Grant senior Claire Bené. “When I had … sex ed in middle school, the first thing was like to have safe sex and to use a condom. And I don’t think that’s the first thing to having sex.”

Because every individual has different experiences, and consent is not a focal point in many sex education curricula, it can be confusing to navigate. Not only that, but there are countless other factors that contribute to this confusion. Oregon laws provide a set of guidelines for scenarios in which it is illegal to give consent, including if a person is under 18 years old, “mentally defective,” “mentally incapacitated,” or “physically helpless.” However, the laws do not provide a specific definition for consent.

When even state laws do not have a clear definition, how can we expect high school students to?

In order to gain a greater understanding of the confusion around consent — and what the Grant community can do to combat this confusion — a variety of students were interviewed about their perspectives and personal experiences surrounding consent.

Amaya Aldridge She/Her Senior

What do you think is the importance of consent?

“I feel like it’s just common respect. I don’t feel like it’s like a privilege or something; I feel like it’s just a right to have respect and consent for another person. I think it’s important because people have boundaries, and it’s not okay to cross them in any way, whether that’s in a sexual way, nonsexual way, just in life everyday. But people should have the right to be okay with whatever’s going on with them.”

What do you think is the importance of already having knowledge of consent before you get to high school?

“That’s extremely important because I feel like as people mature … peer pressure gets intensified, as well as the social climate of what you think you should and shouldn’t be doing as a high schooler. Like there’s a lot of pressure on everyone in high school to be more sexually active … So I feel like that puts a lot of pressure on people. I think it would be helpful to know that you don’t have to (have sex) and there’s a lot of other people who aren’t out there doing whatever, having sex. I feel like that would’ve been helpful, even for me, coming into high school. Knowing that it’s not just me who was uncomfortable or knowing that a lot of other people were comfortable or not comfortable giving consent. So I feel like that education could help with the confidence going into high school or to feel more secure going into high school.”

Could you speak to the gray areas or confusion around consent?

“I know one thing that like, when I’ve done consent workshops, that a lot of people ask questions about is like intoxicated consent, which is technically not consent legally. But people try to like come up with a lot of hypotheticals when it comes to consent which there’s a lot of situations where consent is necessary or where it’s confusing to people. Like at parties where people are under the influence. And sometimes I feel like that’s hard in schools because I think educators are less excited to teach about that because they don’t want students to be under the influence, which makes sense because it’s not legal. But it also happens. So that’s a tough balance.”

Owen Cooper-Karl He/Him Junior

What is your definition of consent?

What is your definition of consent?

“I see consent as an explicit yes, but also kind of a conversation about what they’re saying yes to. And then it’s not just a yes and then from there it’s an implied yes, but kind of by body language and how the person is interacting with you. If they seem to be engaged and okay with what’s going on and kind of throughout the process of whatever you’re doing, whether it’s just kissing or if you’re having sex. Kinda questioning like, ‘Is this ok? Is that ok?’ And making sure that at any point if they feel uncomfortable that you draw the line and you check in again and sort things out.”

Do you think we talk about consent enough in our society?

“No, I don’t think so. I think it’s an uncomfortable topic for a lot of people. I think not just consent but being willing to openly talk about something as personal as sex and what you’re doing with someone you’re intimate with. So I think that’s kind of a hard thing for people to talk about, but also it’s something that I’m sure a lot of people have guilt about or are worried about or have bad associations with it. So I think it’s just a hard topic for people to be willing or open to talk about or be honest about.”

Why do you think it can be so hard for others to practice consent?

“I don’t know. I think some of it ties to that toxic masculinity, and that sort of need to never be wrong, and that idea that you have to be sort of strong and not intimate or caring. So I think that can kind of shut down conversation and create a lack of empathy at points, and a kind of disconnect in understanding or reading someone’s feelings. It’s just not caring, which, I don’t know. It’s a confusing thing for me that some people can not understand something so clear.”

What are signs that someone might feel uncomfortable with what’s happening?

“I feel like for a lot of people, especially if it’s someone you are close to, it’s really hard to say no and kind of either disappoint or hurt them. So you go in with either ‘maybe’ or ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I’m not sure,’ and I think in the moment it can be easy for that to be sort of confused as consent … And of course in the moment there’s the kind of body language of not reciprocating the same sort of acceptance. You can tell when someone’s not enjoying something. You’re there. You’re present.

Claire Bené She/Her Senior

Why do you think that people have a hard time understanding consent?

“I think we live in a culture where consent isn’t the most important thing in sex and out of sex … It isn’t a thing people talk about … I’ve never had a consent talk with my parents, and I know a lot of people that haven’t. And I think that is … why we’re having such a problem later is because we’re not addressing it early and not addressing it in a positive way, I think. As just celebrating giving consent instead of shaming. Which I think we should definitely shame not giving consent, but celebrating that this is the way it should be. This is the way that is healthy, (but it) is something that we don’t talk about. I think that’s a big reason that we have these problems.”

Do you think that you have a deep understanding of what consent is?

“I think I understand the concept, and I understand situations where the concept can kind of be applied, but I think it’s different for each situation. Before I started educating myself, I kind of looked at things and I was like, ‘Well, did I ask for consent this time or did I not?’ And since then, I mean I’ve been more aware of it, but there have been times where I was like checking myself and realizing. And I think that’s okay … You can’t be perfect every single time, and that’s understandable. But knowing that when you make a mistake, knowing that and then I just like come back with my partner and have been like, ‘Are you okay with what I did?’ or something like that. And that conversation has just helped. So I definitely don’t think that I know everything or I do everything perfectly, but I think that just like the baseline of understanding is helpful and then understanding that … you can mess up to an extent as long as you talk about it afterwards, or you realize that you messed up.”

You’ve mentioned that you think sex is considered taboo. How do you think that affects consent?

“With my own conversations with my parents, they don’t like to say anything about (sex) … And I would rather them use all of the, I don’t know, medical words or something like that just to have actual conversations about that … Giving consent is saying you like sex or you want to do it. And that’s something that our society doesn’t like to admit … A lot of people like sex. And I think that’s okay to say.”