Then senior Milena Ben-Zaken sits with fellow founders of Grant’s Let’s Talk club, Sofia Ben-Zaken and Tess Waxman, having just finished giving a comprehensive sex education lesson to a middle school class. A group of inquiring girls approach the high schoolers after the lesson, requesting a private meeting.

Ben-Zaken struggles to stay calm as the girls begin describing their experiences with sexual harassment. One of the girls begins recounting events where boys rated her and other girls as they walked by in the hallway. Some disclose that sometimes they feel pressure to send nude photos, asking how to deal with these situations.

Despite feeling appalled, Ben-Zaken tries her hardest to remain unphased by these stories, attempting to show confidence and support. But by the end of the meeting, Ben-Zaken is shocked that children are forced to deal with such heavy topics without proper education. “Hopefully providing younger kids more broadly and more vastly with education could make a difference,” she says.

According to the Center for American Progress, only six states require education on consent and healthy relationships, two major components of comprehensive sex education.

Grant High School was among the first high schools required to teach the topic when Oregon became the first state to require comprehensive sex education in 2009. Seven years later, California and New Jersey followed suit. In 2015, Oregon passed Erin’s Law, which requires curriculum that teaches children in grades kindergarten through 12 about boundaries and personal safety in an effort to prevent child sexual abuse.

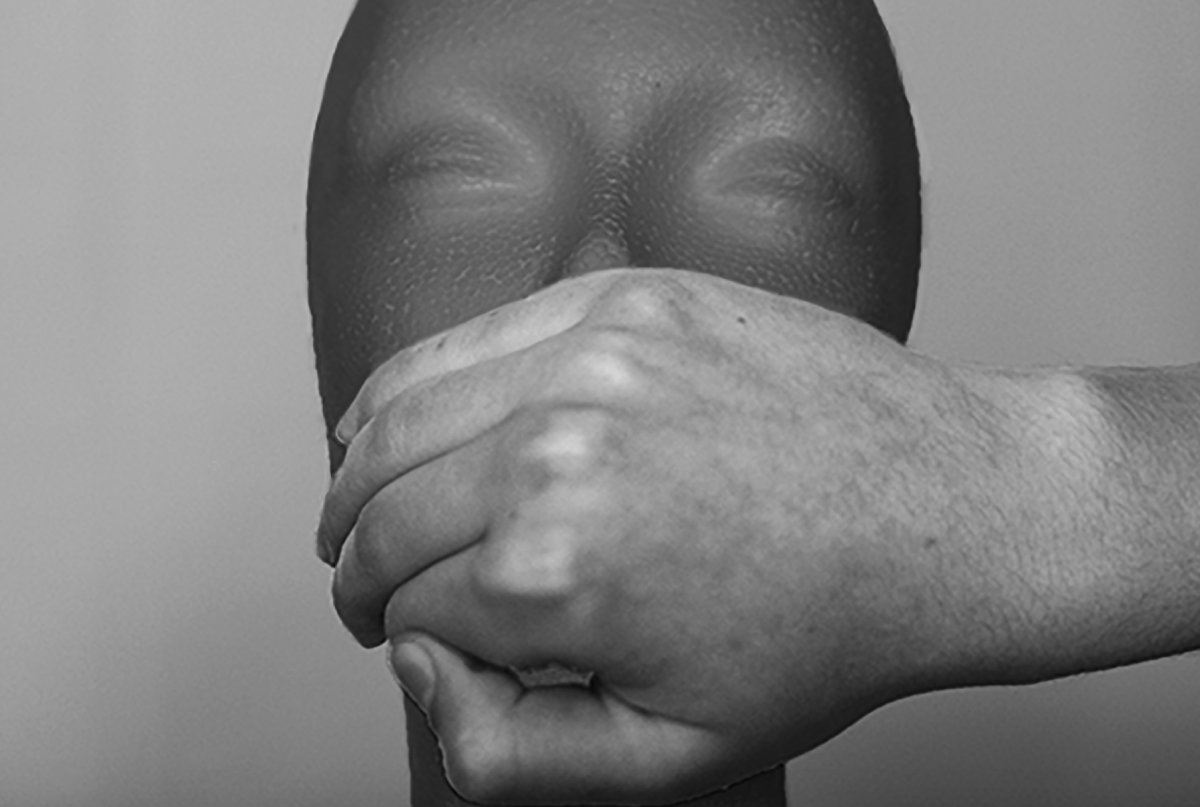

But our society has only just begun the process of combating sexual assault. The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network — an anti-sexual assault non-profit — claims that one in six women is a victim of attempted or completed rape in her lifetime.

Despite its prevalence, sexual assault remains a taboo subject that is rarely taught or talked about, leaving some looking for ways to combat these high rates without the proper tools. Grant junior Eli Pearl says, “It’s such a present thing in the world but so not openly talked about because it’s not taught enough.”

Nicolas Guerrero, the Community-Based Programs Manager at Raphael House — an organization that works to end domestic violence and abuse — believes that our culture still has more progress to make.

“We don’t think about the fact that, you know, our culture is basically based in violence,” says Guerrero. “If we want people to have a life free of violence, not only in personal relationships, we need to look at all the social and cultural dynamics and history.”

To Grant health teacher Erin McNulty, education is necessary in order for these changes within our society to take place.

“We need to really start young and establish that ‘this is my body and I get to control what happens with my body,’” says McNulty. “In school settings, the more we start that at a young age, then we can do age-appropriate health education.

For the last three years, Grant health has used curriculum from Nest — a non-profit that writes sex education curricula for high schoolers in different cities across the country — to talk about subjects such as sexual assault and domestic violence in class.

Amy Collins, a curriculum teacher at Nest, says education around these topics could have a great impact. “I truly believe that a lot of people will do right if they can access the information,” she says. “Denying access to information allows for ignorance and harm to continue to happen.”

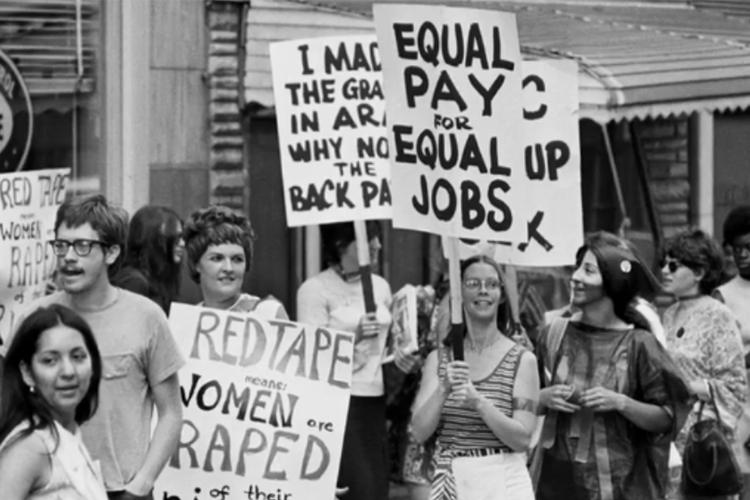

The battle for sex education in high schools is not new. During the 1950s and early 1960s, movements supporting teaching the topic in high schools began gaining national support.

In 1964, the medical director of Planned Parenthood, Mary Calderone, founded the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States in an effort to provide more sex education for American youth. Despite these efforts, the widespread belief across the nation was that abstinence-only sex education — which encouraged teens to refrain from having sex until they were married — was the best method. Students were usually not taught about contraception, STIs, healthy relationships or sexual assault.

Grant math teacher James Tucker recalls learning the concept of “no means no” as an adolescent in the 1970s, meaning that if someone said no, you could not pressure them into sexual acts. Tucker feels that he came away from his PE classes with a strong understanding of this, as well as the physical aspects of a healthy relationship.

Despite having what Tucker thought was an overall successful sex education, he still heard many accounts of physical abuse. “It was a time when I don’t think it was quite like what it is now,” says Tucker. “The best way to say it is they weren’t punished for it. It was just something that everybody said, ‘Oh that’s just life.’”

For Grant health teacher Deborah Engelstad, her education during the late ‘70s was fairly different. “We didn’t know anything about consent, what was okay or not okay,” says Engelstad. “Situations just happened and you felt very alone and knew you couldn’t talk about it, no resources. For many women growing up during this same time it has had lasting effects in terms of the quality and kinds of relationships that have been formed today.”

Up until the 1980s, abstinence-based sex education was widely supported. However, a debate began over whether or not comprehensive and medically-accurate sex education was more effective. Despite growing support for this idea, laws regarding sex education were not changed.

The missing aspects in sex education left some people feeling shortchanged.

Grant health teacher Chris Zeller says, “I never really was educated on victims and how victims can use resources, how they should reach out. So I think in my education I didn’t receive the tools to advocate for others.”

Zeller’s experience was not uncommon. In the 1990s, a decade before Zeller’s high school experience, the majority of teenagers in the United States were still being taught abstinence-based education in school. But more and more research was emerging that showed that comprehensive sex education was more effective.

In November 2007, the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy published “Emerging Answers,” a book summarizing 115 studies conducted over a six-year time span to measure the impact of sex education programs in school. Author Douglas Kirby found that comprehensive sex education programs were the most effective in positively influencing adolescent sexual behavior.

Regardless of the national controversy over abstinence-based versus comprehensive education, Planned Parenthood says that over 95 percent of U.S. parents support the coverage of more comprehensive topics in high school sex education, like healthy relationships and birth control.

But this popular interest is not evident when looking at state laws. The vast majority of states do not mention healthy relationships in their required curriculum, which is a large part of Grant’s comprehensive sex education program. There are only 24 other states in the U.S. that require any type of sex education to be taught in schools.

When states don’t regulate the sex education curriculum taught in schools, students run the risk of either learning false information, or nothing at all. According to a 2004 report prepared for House Democrats called “The Content of Federally Funded Abstinence-Only Education Programs,” abstinence-only curricula sometimes reinforce gender stereotypes that promote ideas of male aggressiveness and female weakness. One curriculum that the study evaluated states that, “While a man needs little or no preparation for sex, a woman often needs hours of emotional and mental preparation.”

At Grant, both McNulty and Zeller recognize the consequences of abstinence-based sex education. In their health classes, students spend a large part of the year learning about comprehensive topics like healthy relationships and consent.

Health classes at Grant provide students with information that many of them previously lacked. While some elementary and middle schools in Portland touch on consent and sexual assault, Grant health classes are often the first place where students receive in-depth lessons about the topics.

“I never really got a consent lesson until last year and that was in ninth grade,” says sophomore Quinn Bennett. “In like seventh grade we had like the ‘No’ workshop, but that was pretty much it. Not really any healthy relationships, and like I still don’t totally know what defines an abusive relationship.”

Both Pearl and fellow junior Ruby Paustian recall learning about consent from family members. Paustian says, “Outside of school I started listening to conversations with my mom and her friends, and I started arguing with people about it in middle school.” For Pearl, an older sister began informing him about sexual assault and other sex education topics.

However, for students whose families do not talk about this topic they are often left with very little information until arriving at Grant, at which point some students are already sexually active.

Julia James, current co-president of Grant’s Let’s Talk Club, recalls a time when the club went

to Laurelhurst school. The club teaches comprehensive sex education to middle school students in Portland, and James was struck by the impact that her club had. “These kids that were going into high school the next year, they had no idea that like things as small as touching someone … can be uncomfortable, and if you think that touching someone is okay all the time … one touch can lead into kissing someone, and then that can lead into something else,” says James. “(The students) were like coming up to me after, and they were like, ‘Thank you so much for enlightening us on this topic, I didn’t know that it wasn’t okay to touch this girl’s hair without her permission.’”

An integral part of the Let’s Talk curriculum is its inclusiveness of different genders and sexualities. The little sex education that James received in school did not cover LGBTQ+ relationships and was based on the concept that gender is binary, only representing students who identify as male or female.

“If you put genders on things, people are gonna be like, ‘Okay well, there’s only education about being a man and a woman. It’s not okay to be myself,” James says.

McNulty also recognizes the importance of teaching LGBTQ+ inclusive sex education. “Within our Nest curriculum we also identify the vulnerability that can happen within people’s lives that can make them more likely to be isolated or assaulted or groomed,” says McNulty. “And those vulnerabilities aren’t just identifying as LGBTQIA+. It’s, you know, homelessness; it’s being in the foster system; it’s socioeconomic status; it’s race. It’s all of these elements. And the more vulnerability factors that you have, obviously the more vulnerable you become.”

LGBTQ+ people experience sexual assault at higher rates than heterosexual cisgendered people. According to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, “44 percent of lesbians and 61 percent of bisexual women experience rape, physical violence of stalking by an intimate partner, compared to 35 percent of heterosexual women.” However, LGBTQ+ people are rarely taught inclusive sex education in order to stay safe and healthy. A 2013 National School Climate Survey done by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) found that fewer than five percent of LGBTQ+ students had health classes which contained positive representations of LGBTQ+-related topics.

Sophomore Mei Zuch recalls receiving minimal and inaccurate LGBTQ+ inclusive sex education when she was in middle school. “If it’s not accurate it kind of, it singles out people who are a part of the LGBT community,” she says. “It makes them feel like … education about us doesn’t really matter.’”

Although clubs like Let’s Talk are important for informing younger and LGBTQ+ individuals, it is not expected that Grant students educate all of Portland Public Schools (PPS) middle schoolers. While younger kids may not be ready to grapple with the idea of sexual assault, Collins believes they can be introduced to concepts that are essential for healthy relationships in a non-sexual context.

“We have classes to have conversations that aren’t explicitly about sex but are the groundwork for those key components of those conversations that we’re trying to convey. And those I think are really important,” says Collins. “We have a lot of places where we could open up the dialogue and not just be like, ‘Oh, we’re gonna come talk to your fifth grader about sexual assault.’”

If children understand the ideas of consent and bodily autonomy at a young age, they are likely to be more receptive to conversations about consent in a sexual setting later in their lives. This in turn can create a better awareness of sexual assault throughout our society.

Despite the progress that our society has made since the 1960s, sex education still has a long way to go. However, this generation has the potential to create change.

“If youth (had) that same sort of magnitude and power (as the gun control protests) with the #metoo movement, or really demanded change in legislation in the ways that we have social norms about what is permissible, how to get consent, it would completely transform culture,” Collins says. “I think that youth are usually the most capable of doing that because they see what is going on and they just have a voice.”

In early November, multiple Grant clubs and many PPS students attended Consent Convergence, a summit where youth came together to talk about consent and various related issues. Junior Violet Muhle Bruce presented at Consent Convergence with her youth-run group, Mental Health Youth Advocates.

Upon walking in the door, Muhle Bruce was struck by how organized the event was. Crowds of teenagers were walking between different interactive stations, coloring pictures of small animals that gave advice on consent, taking pledges to commit to consent or taking pictures in front of a wall that said “Consent? Yes please.”

Seeing all of this emphasized to Muhle Bruce how many people are interested and want to learn about these difficult topics. “I was really happy with how many people I knew (that) went, and some people that definitely aren’t as educated,” says Muhle Bruce. “People came that don’t really pay attention, which I thought was really important.”

For McNulty, events like Consent Convergence are simply examples of the impact this generation can have. “(Youth) are going to be the most powerful generation,” says McNulty. “You have the education; you have the voice; you have the platforms.”