I thought it was just going to be a normal Monday. I couldn’t have known how wrong I was.

It was Nov. 20, 2017, three days before Thanksgiving. I was waiting for the bus to take me to school, as I did every day. Nothing that morning had been out of the ordinary. There was no indication of what was about to happen.

Out of nowhere, I began to feel dizzy. I could hear the people around me talking, but I couldn’t make out any of the words they were saying. I could feel myself begin to fall. Suddenly, I felt myself hitting the hard cement of the sidewalk, and the next thing I knew, I was in an ambulance.

The ride to the hospital was a blur, but things began to come into focus once I was in the emergency room. I could see that my family was there, standing around me or sitting in the hard plastic chairs in the corner. The bright fluorescent lights illuminated their faces. I wasn’t sure what was going on, and that terrified me.

As soon as they saw that I was conscious, I was flooded with questions from my family, mostly about how I was feeling. I talked to them, but I couldn’t truly focus. It was hard to concentrate on their words when I had other things to think about, such as the painful bump on the back of my head and what had happened to me. I wanted to know what had caused my fall.

Finally, a doctor entered the room. She asked me a few questions, but eventually, I got the answer I was waiting for. She told me that I’d had a seizure.

I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t even know what to think. I was stunned. I didn’t know what a seizure was, but I’d heard of the word — from what I could tell, they seemed serious. I didn’t understand how this could’ve happened.

Most of all, I was afraid. What would this mean for me? What would I have to change in my life? Would I be the same person? I had heard of people never being the same after events like this, and I didn’t want to have that happen to me.

The doctor talked more about seizures and the potential causes of mine. She also mentioned that it was unlikely that I would have another seizure, so I shouldn’t worry too much about it. That didn’t make me any less scared, though; I’ve learned that adults telling me to not worry usually means that it’s something worth worrying about.

The doctor and nurses seemed to think that my seizure was just a one-time occurrence and that I should be fine, so they decided that I could get checked out of the hospital. It appeared that I was going to be okay. I’d be back to normal and going to school in no time. A few minutes later, that all changed when I had a second seizure.

I was lucky that I was in a hospital bed, so I didn’t fall and injure myself again. Unfortunately, the second seizure confirmed that I was epileptic and increased the risk that I’d had brain damage as a result of the episodes. The worst part was that my family had to witness the episode. They saw me shaking uncontrollably, eyes glazed and foaming at the mouth. I had never wanted to have a seizure, but for my family to have to watch, unable to do anything, was quite possibly the worst way for it to happen.

I had to stay in the hospital overnight so the staff could monitor me and administer some tests. When they determined that my brain activity seemed normal, they allowed me to leave. I was prescribed a medicine called Keppra to limit the chances of future seizures and was sent home.

Since it had only been a two-day school week, I was able to take the remainder of the week to rest without missing any class. By Monday, I felt well enough to go to school. Even so, I wasn’t able to participate in the capacity I was accustomed to.

Teachers would give instructions, and as hard as I would try to comprehend what they were saying, the words didn’t stick in my mind. I needed to ask teachers to repeat themselves many times, and I felt like I was behind in everything.

Additionally, I had to get used to tracking the amount of time between drinks of water, the amount of time I spent looking at a screen, the sugar content of everything I ate, as well as making sure that I’d taken my medicine each morning and night. It was difficult to try to maintain all of these things, but if I didn’t, the risk of having another seizure would increase.

Throughout everything I was dealing with, the people around me remained kind and supportive. They would always ask me how I was doing and whether I felt better. While I knew that it was because they cared about me, it was exhausting to be constantly asked about my seizures. I didn’t want my epilepsy to define me, but I could tell that it was changing how people thought of me. They were starting to associate me with my condition, as if that was all I was.

I wanted to talk to someone about my epilepsy, but I didn’t know anyone else who had personally experienced what I was going through. I’m sure that my family or friends would’ve listened, but they wouldn’t have been able to actually relate to me. I would have to go through this myself.

I wanted my life to go back to the way it had been before my seizures. Back then, I didn’t have to answer the question “How are you feeling?” dozens of times a day. Back then, I didn’t have to closely monitor every part of my life. Back then, I didn’t have to deal with being epileptic. Now, my life was completely different, and I didn’t know if it would ever be the same as before. I was terrified that these changes would become my new normal.

Suddenly, I was spending my life in constant fear of having another seizure. Although I was taking the medicine, I wasn’t immune to seizures. I ran the risk of seizing up at any time and in any place. I had no control over what happened to my body. I spent many nights lying in bed, unable to sleep because I was panicking at the thought of experiencing another epileptic episode.

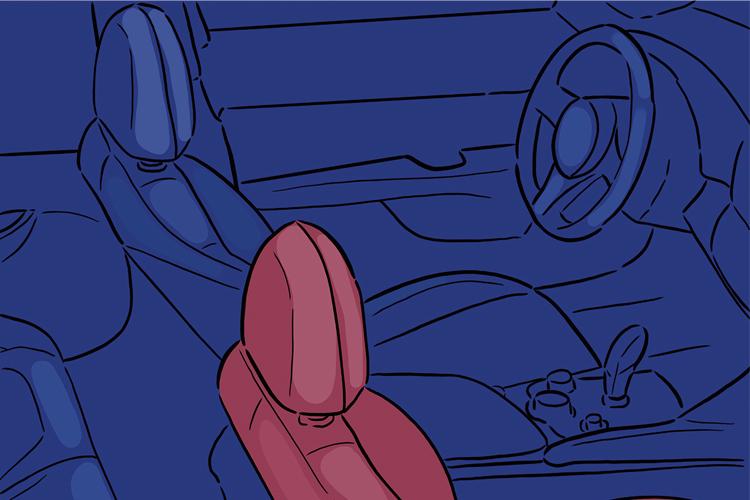

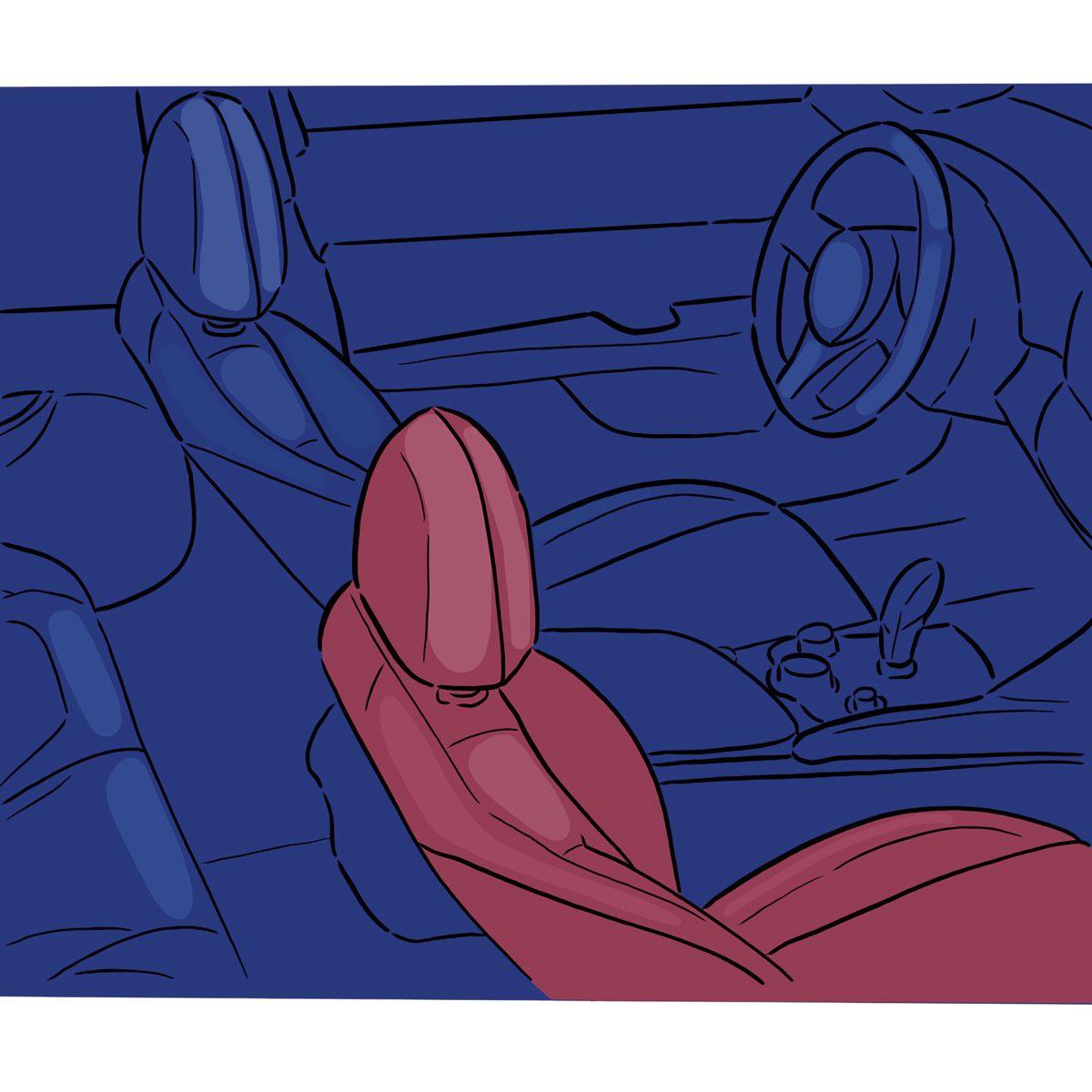

I felt less like the driver in my life and more like a passenger. My epilepsy was tightly gripping the wheel, and didn’t appear to be letting go anytime soon.

Throughout the whole process, my family and friends tried to help me as much as possible. Initially, I thought that it was just out of sympathy. However, when my parents told me that they’d found a “seizure toolkit” online containing the necessary information for people to help me if I had another episode, I knew that it was more than that. Knowing that they cared enough about me to learn all of that information about my seizures made me feel supported. For the first time in this process, I didn’t feel alone.

Motivated by my newfound support, I pushed myself to adjust. I asked teachers to repeat themselves if I needed it. I wrote down things I needed to remember because I knew that if I didn’t, my epilepsy would cause me to forget it. I made myself re-read sentences to make sure that I understood them.

Eventually, it got better. I felt more and more like my old self. Worrying about my seizures had taken so much of my time and energy that it made me unhappy, so I contemplated my worrying and, more specifically, why I did it. I couldn’t figure it out. After all, it didn’t help the situation.

That’s when it hit me: If worrying didn’t help me, there was no reason to do it. All it did was bring unnecessary stress. If I spent all of my time and energy worrying about a potential seizure, I was letting my condition win. I decided that since it was pointless to worry about it, I should stop.

More importantly, all of the things I was doing felt like they were working. For the first few weeks, my efforts to prevent another seizure were mediocre. I didn’t always control my screen time or sugar intake as well as I could have. Because of this, I still felt dizzy or tired. After realizing that the two were likely correlated, I started to try to monitor myself more. The more I tracked myself, the less dizzy and tired I felt.

The increase in self-monitoring also helped to give me more of a sense of control. I realized that I could affect whether I had another seizure and that I wasn’t at the mercy of my condition. Slowly, I began to take back the wheel from my epilepsy.

Even now, I don’t feel that I have completely recovered. I feel different, and I may always feel that way. I still have to read things multiple times to understand them more than I used to. I still feel that thinking and problem solving takes a little more effort. However, I did gain something from my experience.

Before my seizures, I’d never even broken a bone, so to have something of that severity happen to me was frightening. But I survived. I now know that if I can survive and recover from multiple seizures, I have no reason to be scared anymore.

After I had my seizures, I decided that being less afraid would be in my best interests. I couldn’t have known how right I was going to be.