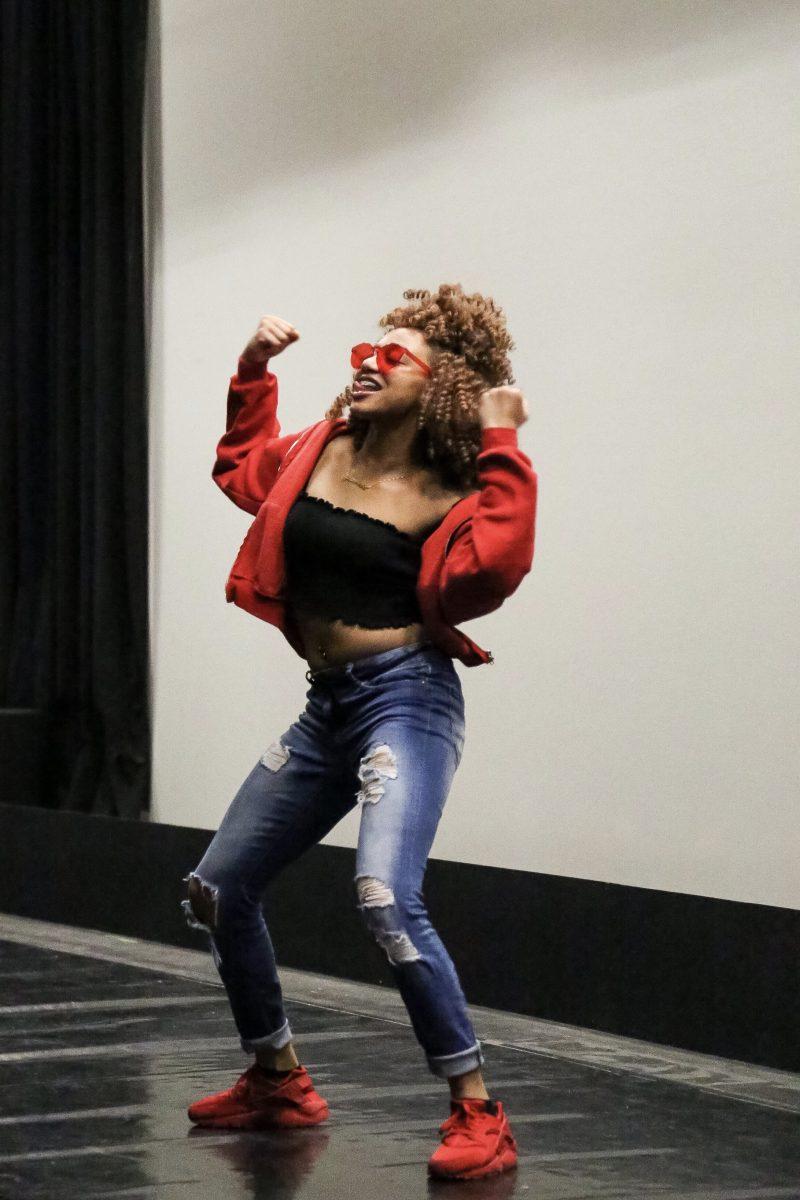

Jai’aja Winchester stands backstage during Grantasia – a holiday themed performance – shaking. The butterflies in her stomach are an unfamiliar experience for her.

While awaiting the end of another dance, Winchester and the rest of her group, the Grant Dance Collective, huddle together in prayer. Then, they enter the stage, clad in black hoodies symbolizing the tragic shooting of Trayvon Martin. The dancers all lay down on the stage, completely still.

As haunting piano music begins, the dancers rise in unison, as if rising from the dead. The music shifts into rap and Winchester steps out for a solo and krumps to the lyrics, “Police been firin’ and they gon’ keep firin’. The government been lyin’ and they gon’ keep lyin’.”

She stands still as two other dancers complete their solos. When the song gets to the line “F*** your feelings,” the dancer shout along. A large huddle of dancers in the background take off their hoodies, while Winchester and three other dancers in the front hold their hands up, mimicking an interaction with a police officer.

The music slowly fades out and Winchester stands holding the hands of her GDC teammates. Tears stream down her face and she notices similar emotions being expressed by her peers. “I felt … that fear, but it wasn’t for myself,” she says. “It was for my friends, it was for my family, it was for people of color. And I think we all shared it in that moment and that’s why it was so powerful.”

Winchester has been involved in dance from a young age, enjoying being able to express herself artisitcally and emotionally.

She no longer lives with either of her parents, having bounced around between homes when she was younger. She eventually made the decision for herself that she would rather live with her godmother, Terri Tree. She now finds support within the dance community at Grant.

Through dancing and choreographing, she is able to work past her struggles that she has found at the many schools she has attended, and as a Black woman in America.

“You can express yourself throughout your body without words,” says Winchester. “Within a lot of things that I go through, I always turn to dance to speak for me.”

Winchester was born in Portland, Ore. on March 15, 2000. She showed an interest in arts from a very young age. She wrote stories and plays, took photos, and acted as well as danced. “We always had dance classes and we also went and saw a lot of performing arts,” says Tree. “A lot of music. A lot of dance. A lot of theater.”

Winchester began dancing at age three at a studio that combined gymnastics with tap and ballet. She recalls going down in the splits or landing a turn while in dance class. She would look up and see the proud grins from her family members watching. “We went through a lot, and so I remember liking smiles,” she says.

Winchester continued to dance throughout her elementary school career. She attended five different elementary schools and bounced around from the houses of her father, mother, and godmother.

During the after-school program Schools Uniting Neighborhoods (SUN) in her fifth grade year, Winchester was exposed to stepping– a form of dance common in the African-American community where dancers create beats with their bodies. “I instantly liked it because I liked the fact that you could make music without music,” she says.

Winchester unintentionally began incorporating step into her own dance. She recalls dancing in a talent show that same year to “I Whip My Hair Back and Forth” by Willow Smith. She included elements she had learned from the SUN program, all of her movements aligning with the beats of the song.

Before sixth grade, Winchester and her mom moved to Phoenix, Ariz. for a change of pace. There, Winchester struggled. She attended a charter school with a majority Hispanic population; she was the only Black girl in her whole grade, and one of the only people who couldn’t fluently speak Spanish. She found it difficult to connect with others, and felt she had nothing in common with anyone. Teachers would often have to translate to English just for her, which didn’t help her feeling of isolation.

Other students noticed this and took advantage of Winchester. “I think I was angry about a lot of things and then when people picked on me … I was just like, ‘Lets go, let’s fight,’” says Winchester.

After a year and a half in Phoenix, Winchester and her mother and siblings and her grandma moved to Houston, Texas to live together. Winchester was beginning to feel frustrated with moving so frequently, having entered a new school during the middle of seventh grade. “It was the most irritating thing I could possibly go through because I was just always behind (in school),” she says.

Before she was able to completely adjust to life in Texas, Winchester was sent to live with her father, his girlfriend and their two kids back in Portland the summer before eighth grade.

Winchester’s father had never been very involved in her life. “When I was younger that really touched me, and I hated him for it,” she says. “But now that I’ve gotten older I was like, you’re gonna do what you’re gonna do. I’m not gonna sit here and beg and plead for you to stay in my life.”

She felt on the outside of the family dynamic, being the only child with a different mother. No one tried to make her feel more comfortable, or even welcome. She recalls one Christmas where her siblings all got expensive presents while hers came from the Dollar Tree.

“It felt like I was there because my mom dropped me off at the doorstep … and not because he actually wanted me,” she says. “He’s my father, but there’s nothing further than that, there’s no relationship.”

Winchester was able to move back to Houston at the end of eighth grade and she felt relieved and excited. There she started a step team, which eventually merged with another step team. This was a much stricter dancing experience than she had previously encountered and it pushed her to become more dedicated to dancing.

Eventually, Winchester became co-captain and stepmaster – someone who runs practice and makes the steps – as an underclassman. This was already a rare feat, but Winchester was also the only team member to hold two positions at once. “I think since I had two positions it made me really strict on myself to get things done,” says Winchester.

Having so much responsibility led her to learn to manage a team as well as to understand the meaning and intent of step. “It’s what somebody would consider ghetto … but in step they praise that,” says Winchester. “I can be aggressive, but in a really powerful way.”

Halfway through her sophomore year, Winchester made the decision to move back to Portland to live with her godmother to get away from her mother’s divorce, and to get back on track with schoolwork.

She enrolled at Grant High School. As usual, the transition was not seamless for her. “I did not talk to anybody and I would have my headphones in and I’d be talking to my friends from Texas,” says Winchester. “I really did just hate it at Grant my sophomore year.”

At Grant, Winchester felt alienated as a Black woman in a sea of white people. She found this particularly obvious in the schoolwide Race Forward. “I was already a new person at this school and, like, for them to make me feel like I had to speak for my whole race was hard,” she says.

That year, she was placed into the intermediate dance class at Grant. Jessica Murray, Grant’s dance teacher, could see Winchester’s talent from the beginning. “She is an excellent performer,” says Murray. “She has impeccable musicality. Just one of the best.”

By the end of the year, Winchester was choreographing and helping teach the dance class. That summer she made it into GDC, a try out only dance group. “If she just went to some other school that didn’t have (a strong dance program) she would’ve been lost,” says Tree.

Winchester also made it onto the Gendrills, Grant’s dance team. However, she did not enjoy her experience there and left after three months.

Although hip–hop was her favorite style, Winchester began taking classes outside of school to develop her skills in other styles of dance, such as vogueing, salsa, ballet and contemporary.

During her junior year, Winchester began trying to change herself in order to make friends after hearing most people thought she was unapproachable. “I looked mean and stuff like that. I think the way that I changed myself is called code switching,” says Winchester. “Code switching is when you change up kind of who you are, like you try to present yourself in a way where like you sit up right, you have a nicer, higher voice, you articulate your words more.”

While visiting old friends in Texas, they made fun of her for “acting white.” She didn’t believe them initially. But when they called her by her full name, Jai’aja, she realized they were right. In Portland, Winchester had gone by Jai. “It kind of opened my eyes to see that I’ve made two of me to assimilate to the white Portland culture,” says Winchester.

When she arrived home after the trip to Houston, she decided she was done trying to act in a way that would make the students at Grant more comfortable.

“It was breaking me down,” says Winchester. “I felt like I was altering myself for other people so that I could be accepted.”

But in GDC, Winchester felt at home. She enjoyed the opportunity to perform at a higher level, as well as the friends she was able to make there. “If it wasn’t for the dance program, GDC, Murray,” says Winchester. “I would definitely still hate it (at Grant). Just hands down.”

That year, Winchester brought step to Grant, offering up her experience from stepping in Texas. “It’s a nice place for a lot of women of color to come together and do something that we all love,” she says. “It made me get in with the Black community (at Grant).”

Seeing potential in Winchester, Murray began to push her to choreograph, something Winchester had only briefly done with step in Texas.

When choreographing for GDC, Winchester found she was drawing inspiration from social justice issues. One of the first times she had an experience with this was when helping choreograph to “Might Not Be Okay,” a song about police brutality.

Choreographing this piece was very emotional for Winchester. Every time she heard the song, she would cry. But her connection to the music and intent of the dance made the actual choreography easy. “Even something that you can’t explain,” she says, “you can do it with dancing.”

GDC originally planned to perform this dance in Grantasia but it received a lot of backlash for not fitting the theme. “I was upset because … it’s not like Black people or minorities get to choose a day when we don’t have to deal with … stuff that we have to deal with everyday,” says Winchester. “It’s not because it’s Christmas that we don’t have to deal with police shooting us.”

Eventually “Might Not Be Okay” was approved to be in Grantasia. Winchester feels that being allowed to perform this dance validated the dancers’ experiences. It has since been performed at other dance shows and at Black Student Union assemblies.

While in GDC, Winchester met fellow junior, Keeshawn Bullitt. The two formed a friendly rivalry and pushed each other to get better in their main style of hip–hop. Outside of school, they began to train together with D’Shawn Lampkin, a former GDC dancer.

“They were really close, like siblings,” says Murray of Winchester and Bullitt. “They developed this really deep relationship and bond through dance.”

At the beginning of Winchester’s senior year, Bullitt passed away. “We were so ready for this year, and to see how far we were gonna come and how far we were gonna push each other,” she says.

Winchester contemplated quitting dance because of Bullitt’s passing but after speaking to a friend, changed her mind.

“You have the weight of yourself and this other person who wanted to make it but … didn’t,” says Winchester. “I gotta do it for the both of us, and I’m not gonna let anybody get in my way of that.”

Winchester has gotten to a place where choreography, particularly with hip–hop, is almost easy for her. “She’s churning out choreography so fast for me,” says Murray. “It’s kind of amazing how quickly she can create.”

This year, Winchester was recognized at Portland State University, along with 15 other seniors, for her senior thesis in African–American Literature. She chose to write about the myth of the absent Black father, drawing inspiration from her own life experiences. She felt nervous speaking in front of a large group of people but ultimately enjoyed the experience.

When performing at middle schools for GDC, Winchester was asked to come and teach step to students through a SUN program. She was excited about the opportunity; it felt that she was coming full circle from when she first learned step.

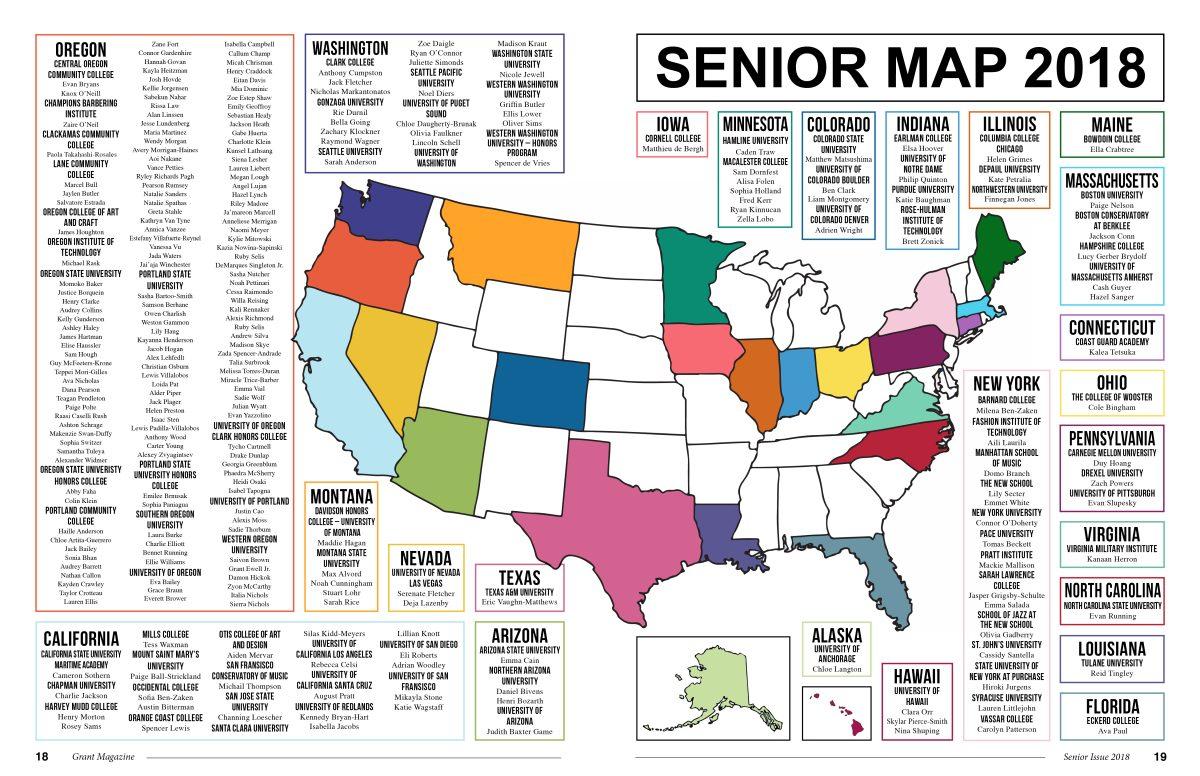

After high school, Winchester wishes to continue dancing in Los Angeles or Portland. She likes the dance scene in LA and feels she would fit in well there.

However, she finally feels as if she has found a community in Portland. “Moving around a lot has really made me see that I don’t like to be unstable and not have that security,” she says. “And here is the first time that I feel secure and this stability.”

While she is unsure of where she will continue dancing, she knows dance will definitely be in her future. “It’s helped me learn how to express my emotions in a different form and so it is not only a fun act to be a part of, but it’s also, like, something I use to just be able to express myself or heal from,” says Winchester. “Whenever I’m going through something, I know I can turn (to) dance.”