Avery Morrigan-Haines paces nervously backstage at Battle of the Bands, a local youth music competition, listening to distant cheers and the music of a competing band. The butterflies circling his stomach and the thoughts bouncing throughout his brain leave Morrigan-Haines filled with anxiety, wondering what reaction he will receive at the end of the night.

Suddenly, the moment comes. Morrigan-Haines hears a voice calling up The Castaway Kids and he climbs onto the stage. Instantly, he senses the blinding hot lights and the hundreds of eyes immediately falling upon him and his band mates.

Picking up his guitar, Morrigan-Haines feels the familiar shape of the orange Danelectro with lipstick pickups — which help convert the vibrations of the strings to musical sounds — bringing him back to all of his rehearsals preparing for this moment. Then, through the noise of the crowd comes a distant, “One, two, three, four,” and before he knows it, Morrigan-Haines, then an eighth grader, is playing his first concert with The Castaway Kids.

He instantly relaxes into the notes and chords of the music. All of the previous built-up anxiety and stress disperses and he becomes confident in the songs that he helped create, letting his fingers glide along the strings in a pattern that has become muscle memory.

As they continue, Morrigan-Haines begins to feel a conversation forming between the performers, the audience and the music — something he had yet to experience at past performances.

Morrigan-Haines’s grasp of time slips away and before long, The Castaway Kids are reaching the last measure of their final song. In his head, Morrigan-Haines slowly counts those last four beats and when he reaches the fourth note, a sense of accomplishment like none other rushes over his body.

“That moment before you land on the last moment is like a million bucks, it’s such a cool moment. At every show that I’ve played, you don’t want it to end, but you want to hit that last note because it is such a powerful moment,” he says.

Growing up playing music, Morrigan-Haines quickly found himself more interested in expressing himself through chord progressions than diving into school books and homework.

Upon joining a band called The Castaway Kids in eighth grade, Morrigan-Haines instantly became more dedicated, spending hours playing and practicing for the moments when he was able to play live music.

“If I’m passionate about something, then I will dedicate hours to it, but that’s because I am able to move around … but when I’m at a desk, I’m just stuck there, and my head doesn’t work that way,” says Morrigan-Haines. “It’s really hard for me to focus.”

But it wasn’t until the departure of The Castaway Kids’ lead singer that Morrigan-Haines began to write more of their music. Morrigan-Haines had grown up connecting to musicians and loving that feeling, but when he started sharing his own music, he learned about the other side of that relationship. “Being on the other side of that is just as magical because you get to make other people feel that way. You get to be a puppet master of emotions,” says Morrigan-Haines.

After his revelation, music looked different to Morrigan-Haines. “(When playing music), my goal is to make people feel sad, or happy, or lighthearted, or nostalgic, or bring someone back to some moment in their life, and maybe they can relate to it, and they feel something,” says Morrigan-Haines. “This is why I enjoy music, because I enjoy stepping into other people’s minds, so why not invite others to step into mine?”

Born on April 14, 2000, Morrigan-Haines remembers a childhood filled with different art projects encouraged by his mother, Shaney Broome. While he was dipping his finger into a bucket of paint or building mud castles, Morrigan-Haines could always hear music blasting through the living room speakers.

As he approached his first years of elementary school, Morrigan-Haines’ parents wanted to find a way to keep him close to his art-filled upbringing. In order to do this, they looked into the Portland Village School, a local public charter school that integrates art into the majority of their curriculum.

However, Morrigan-Haines’s parents didn’t think that the music program at the Portland Village School was enough to fill their son’s musical needs. Broome knew that she wanted all of her kids to play music, so she responded to an advertisement and signed Morrigan-Haines up for his first guitar lessons.

Although he hated the repetitive chord progressions and structure of the lessons, Morrigan-Haines enjoyed showing off his newfound skills to his peers, hauling his guitar through the crowded hallways of Portland Village School every few weeks.

As chords began to come together in different progressions, Morrigan-Haines spent more time experimenting with different patterns, slowly moving towards writing his own songs. His parents saw this motivation and decided to sign him up for a program called School of Rock, which allows kids and teenagers to experiment with playing live covers.

Climbing onto the stage for his first performance at School of Rock, Morrigan-Haines had no idea what to expect. But after settling into his surroundings, he knew he had found where he wanted to be.

“To see the stage, the lights, the crowd and all that jazz … I was like, ‘Hell yeah, this is where I’m supposed to be at,’” says Morrigan-Haines.

As he entered middle school, he left School of Rock and began spending hours in his garage playing different chords and scribbling down different patterns.

Strumming chord after chord, Morrigan-Haines would feel his fingers slowly growing numb in the cold garage. But he couldn’t bring himself to put down his instrument, with unfinished homework lingering in the back of his mind.

Morrigan-Haines soon decided that he needed to buy his first guitar. He cracked open the box and as soon as his eyes fell upon the Danelectro — soon to be named Roxanne — he was in love.

Later that night, Morrigan-Haines slept with the guitar, refusing to separate himself from the instrument.

Upon reaching eighth grade, Morrigan-Haines was invited by a close friend to play with The Castaway Kids in a local Battle of the Bands. He jumped at this opportunity and climbed onto the stage behind his older bandmates.

“That moment of seeing the crowd and being like, ‘This is our s***, we’re doing it, it’s not a cover, we made this’ — that part of it was really cool because it was like an immediate passion, and then I kept doing it,” says Morrigan-Haines.

After winning Battle of the Bands, Morrigan-Haines was invited to permanently join The Castaway Kids as their new guitarist. Morrigan-Haines felt less experienced, but having the other band members as role models made him eager to learn.

To help himself learn, Morrigan-Haines would experiment with different beats and lyrics on his own. Even though he lacked a stage to perform on, he soon discovered the relief he felt after writing both his anxiety and his happy emotions into his lyrics. “I could talk to people, but I’m not that good at it. Music is just an outlet for me,” he says. “I think I would be more bottled up, and introverted if I didn’t have music to put my feelings out there.”

After eighth grade, Morrigan-Haines left the Portland Village School and enrolled at Grant High School, along with the rest of the members of The Castaway Kids. “I would grow to know them super well,” he says. “By the end of it, it felt like they were my brothers.”

Embracing this tight-knit community, Morrigan-Haines felt as if he had become a part of a second family.

Entering sophomore year, Morrigan-Haines enrolled in Beginning Audio Engineering, taught by Branic Howard. “I noticed that he had a pretty keen ability to write songs, and they were songs that he was writing completely on his own, and they were quite good and I was taken by that,” says Howard.

Howard saw potential in Morrigan-Haines, but wanted to let him experiment with the equipment to find his own unique sound. “I love to learn from just doing stuff, and trial and error, and having mentors like Howard along the way, that allow me to have the freedom that I did in that class, definitely inspired me,” says Morrigan-Haines.

As his audio engineering skills grew to be more adept, Morrigan-Haines was approaching his last concert with The Castaway Kids before the lead singer moved to Chicago.

When their farewell concert was reaching the final notes, Morrigan-Haines could feel a chapter in his life closing. Even though the song was not over, Morrigan-Haines began to jump, building the excitement, trying to make the last moment even more memorable. “It was surreal,” says Morrigan-Haines.

After the departure of their lead singer, the remaining band members wanted to continue to play together, but decided to switch their name to Atless. Without a singer, Morrigan-Haines saw his opportunity and stepped up.

As the lead singer, Morrigan-Haines had more say in the songs they wrote. “I think that was the changing point,” says Morrigan-Haines. “That’s when I started really liking to convey emotions and such.”

After performing his own songs and lyrics live, Morrigan-Haines would come home ready to sleep wherever he could, but a sense of accomplishment and motivation pumped through his veins. He felt like he was continuing the cycle, regifting all of the emotions he had felt listening to his favorite artists.

Despite having plenty of experience playing covers and songs written by his bandmates, none of it was the same as the feeling he got from performing his own music.

“Playing your own music is so much different than playing other people’s music. You feel a lot of things internally, so putting that out onto a song, or paper, was a way to translate that,” says Morrigan-Haines. “Maybe I can make someone relate to what I am feeling or take someone back to a moment in my life that they can relate to, or have experienced as well, or would like to experience. That’s just the magical thing about music.”

The final bell of the day rang through Grant’s hallways, but instead of heading for the exit, Morrigan-Haines walked quickly to the audio engineering room. Howard had encouraged him to spend more time recording after school as well as in class. As Morrigan-Haines watched Howard unlock the door, he could feel excitement filling his body. Although the room was familiar, Morrigan-Haines felt like he was exploring uncharted territory, never before having the space to himself.

“That first day, I spent like two hours in there, I just couldn’t stop,” says Morrigan-Haines. “I’ve spent so much time imagining (my songs) and what they’re gonna sound like, envisioning what it would sound like with the rest of the instrumentation … Having that all come together after all that thinking was a pretty cool feeling.”

For the majority of his junior year, Morrigan-Haines would find himself in the recording room at least two times a week after school. Howard guesses that Morrigan-Haines spent roughly eight hours every week recording.

Having all of the recording tools was motivational for Morrigan-Haines. “I would be like, ‘Hey, next week I want to go in and record this song,’ which encouraged me to make those songs and then record because I knew I had the ability,” says Morrigan-Haines.

Howard was taken aback by this developed dedication, but also noticed Morrigan-Haines’s ability to step into the listener’s shoes. “He’s capable of understanding how a listener hears music. That’s another thing that’s hard for young musicians, to imagine the way that someone else is gonna see your thing,” says Howard.

During this time, Morrigan-Haines would also help his bandmates record songs for Atless, but at the end of his junior year, Morrigan-Haines’s bandmates graduated and he was left recording by himself.

With more time in his schedule, Morrigan-Haines saw an opportunity to pursue audio engineering as a career. He soon started taking a class called Live SET at Mississippi Studios where he learned about maintaining a stable job in the music industry.

For Morrigan-Haines, this deepened his drive to pursue audio engineering. “The main influence of being in audio engineering is so that I can have music in my life,” says Morrigan-Haines. “That’s the goal, just to always have it incorporated in my life because that’s what makes me happiest.”

Morrigan-Haines refused to put down live music altogether. As he sat in his room, guitar in lap, Morrigan-Haines scribbled down chords, already planning out in his head the ten different parts, between guitars and vocals, that he would record for this song.

But even though Morrigan-Haines loved playing and planning songs on his own, it didn’t compare to his times with Atless.

So when he heard that everyone from winter of senior year, Morrigan-Haines said, “‘We’ve got to put this together,’ because them leaving made me realize how special of a connection we had, just as artists, and as friends. I feel like I needed one last show with them.”

The instant Morrigan-Haines hit that first note, he knew time was going to fly and by the end of the show, Morrigan-Haines regretted not making the night last longer. “Since they had moved away I had realized how much I loved it. I had kind of gotten used to performing and all that, of course I loved performing then, but then having a time period when I wasn’t able to perform made me realize how much I really did appreciate and love it,” says Morrigan-Haines.

After this final concert, Morrigan-Haines went back to performing solo, recently performing in the center hall of the Marshall building. Standing with his guitar, a foot pedal, a speaker and a mic, Morrigan-Haines spent the entire lunch period singing his originals. As people passed by, many stopped and watched for a few songs before heading to lunch.

“Just having your peers around you is nerve-wracking, they weren’t paying to go see a show, they weren’t paying to go see me, you know, it could’ve been any sort of feedback. But once I got up there, I was chilling, it was fine, I got some people to stick around. It was good,” says Morrigan-Haines.

In the near future, Morrigan-Haines is hoping to perform at least one more concert with Atless. In order to do this, he has been talking with Friends of Noise, a local non-profit that encourages all-age concerts, and the organizers of the music festival Pickathon to allow youth bands to perform at this year’s festival.

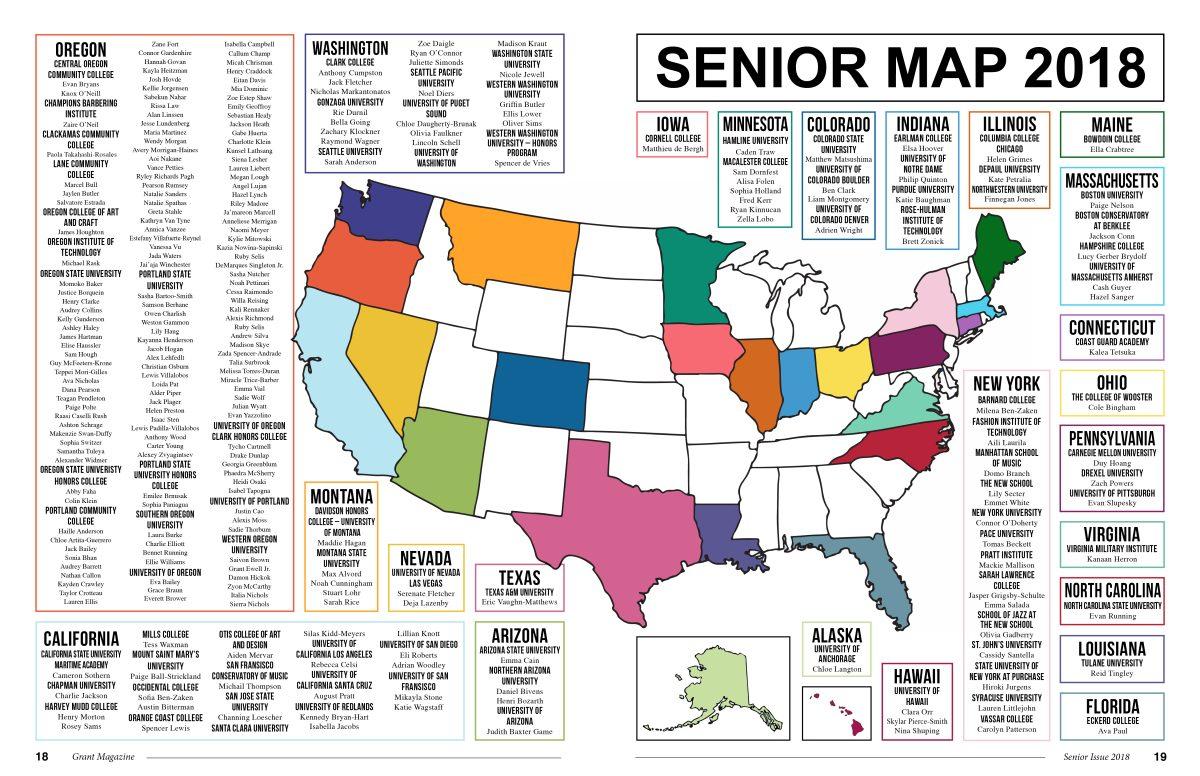

Next year, Morrigan-Haines will be attending Portland Community College (PCC) to earn more credits and work in Portland. After a year at PCC, Morrigan-Haines hopes to transfer to a larger school where he can obtain a degree that can help him pursue either music or audio engineering.

“I would love to be a sound guy at some point, just because it means traveling, a lot of sleepless nights, and time changes … but I think I would love that. That’s a lifestyle I’m totally fine with,” he says.

Morrigan-Haines believes that because of his new-found audio engineering skills, and his experience with evoking emotion through music, he could successfully help artists translate their ideas into their tracks.

“Knowing what an artist is like onstage, and knowing what that experience is like, it definitely helps an engineer because then you know what they want,” he says.

Howard supports this idea, and sees a very bright musical future for Morrigan-Haines. “I think that whatever he pursues he will be successful in, because he has the drive and the passion that is required,” says Howard. “I can definitely see him taking other people’s music and threading some of his own ability into it, and making it better than they could ever make it.”

However, nothing is set in stone. As of now, the only constant he can see in his life moving forward is music. Morrigan-Haines’s time with the orange Danelectro with lipstick pickups, The Castaway Kids and Atless will never be forgotten, and will continue to define who he is and who he continues to be.

“I’ll always find a way to play music, whether it’s by myself, or with a group, or with family, I will continue playing around and finding what I want to do, and keep experimenting,” he says. “I think that because I get so much joy out of it, I don’t see myself stopping anytime soon.”