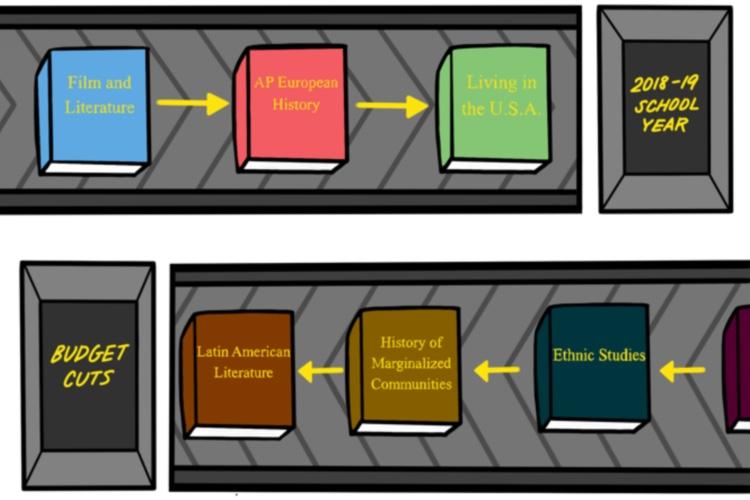

It’s early April at Grant High School and counselor Tearale Triplett talks to a junior English class about forecasting for the 2018-19 school year. Triplett puts a document onto the projector screen, revealing the classes that have been cut for next year. Among them are Latin American Literature, Ethnic Studies, and History of Marginalized Communities — some of the only classes at Grant that teach about societies and cultures other than those of white America.

Although Grant cuts classes every year due to traditional lack of funding, higher priorities are not made for these culturally inclusive choices. But these classes, which aim to teach about groups who have been historically oppressed, are crucial when students are venturing out into life post high school.

Over 500 Grant students identify as non-white, yet there are only 10 teachers of color currently employed at the school. This lack of diversity among both educators and the student body limits students’ abilities to empathize and positively interact with those from various backgrounds, thus potentially leading to conflict when faced with these situations.

According to the Grant administration, courses are cut due to low forecasting numbers. Courtney Palmer, an upper-level English teacher, explains that there simply isn’t enough money to have teachers teach subjects with only enough students to form one class, as each subject taught requires one additional period of preparatory time. Ethnic Studies teacher Lynn Yarne says that only 17 people forecasted for her class for next year. So while it’s illogical and cost-prohibitive to continue offering the class, it is essential to find the root of this lack of forecasting.

Instead of letting these classes disappear, Grant needs to make them more of a priority.

Pitching these course options can help increase interest, but many of these classes are social studies electives which don’t sound as appealing to students when compared to the popular array of art and music classes available at Grant.

“Some (students) are just more interested in visual or performance art, but I also know that some go into those classes expecting an easy A, which is unfortunately very common,” says sophomore Grace Guyer. “If more classes like Ethnic Studies were more prioritized and were required, it would have more success.”

Ethnic Studies and Living in the U.S.A. teacher Marta Repollet advertised her and Yarne’s class at the curriculum fair this past February, though it was not a success. “At curriculum night I had hardly anybody coming to my table, even though I had a table full of student work, showcasing everything we do, but it just wasn’t a priority,” she says.

To combat these issues, a few Grant teachers have devoted time outside of teaching hours to include more culturally diverse units in their classes while still fulfilling state history standards.

“We spent a good portion (of time) on the Black Panthers and black culture in America,” says junior Harper Eaton of his Living in the U.S.A class. “We actually went on a field trip to see Black Panther and see the different side of the American movie industry where not as many black people are able to be portrayed in movies like that.”

But simply relying on proactive teachers to creatively incorporate this material into their classes isn’t enough. While there’s been discussion of Ethnic Studies becoming a required subject in all Portland Public schools within the next several years, something has to change now. This lack of a cultural education can lead to misunderstanding, disconnection, and isolation when graduates eventually encounter people unlike them. The hateful student-orchestrated graffiti towards the Japanese-American community at Grant Park last spring is just one example of this insufficient education causing real, criminal issues.

Going forward, Portland Public Schools needs to install rules and regulations that demand these topics be taught in every high school, no matter the political or cultural views of the staff and students.

Making these topics required instead of relying on students to decide if they want a culturally diverse education would be immensely beneficial to students’ post-high school interactions. “Ethnic studies is essential because it provides young people access to the full spectrum of human knowledge, not just parts of it,” says University of Pennsylvania

professor Dr. Ebony Elizabeth Thomas.

We cannot expect students to leave their senior year educated enough to navigate the world if we only require them to learn the history of white culture and test them solely on events that happened centuries ago.

“A lot of people won’t stay here (after high school) and what happens when you leave that weird little Portland thing … that has cultivated this white liberal sensibility about it that’s based on book learn(ing) and not actual experience,” says Palmer. “Ethnic Studies is not an elective, it’s our lives. It’s how we interact with different kinds of people on a daily basis. It’s every single one of us.”