Due to the sensitive nature of the story, student sources have been made anonymous.

Grant junior S slams the car door shut as she throws herself onto the front seat, avoiding eye contact with her mother. Barraging her with questions, S’s mother attempts to prepare S for her monthly psychiatrist appointment, but the February rain beating down on the car’s hood drowns out her voice.

As S pulls away from the curb, the hours of drinking and smoking marijuana and cocaine that day take their effects on her. The brake lights of surrounding vehicles begin to blur into a combination of colors, intensifying S’s confusion. Every movement — even the turn of her head — is delayed as her senses numb.

At the psychiatrist’s office, S collapses onto a couch. As she chews a piece of gum to mask the stench of alcohol in her breath, the office’s dog, August, jumps up to comfort her. She can hear her mother and the doctor talking, but the drugs make it hard for her to understand their words. S breathes in the dog’s cinnamon-scented coat and closes her eyes. Slowly, the confusion eases as S lets the world around her grow dark, passing out with her legs thrown over the arm of the couch.

The following morning, S’s eyes slowly blink open as she takes in her surroundings: a small triangular-shaped room with unfamiliar white walls. Sitting up on a plastic blue mattress, S watches as other teens make their way past her. Confused, she rises to follow the stream of people.

As her bare feet slap against the tile floor, one of S’s peers tells her that she is in rehab. After S spent more than a year dealing with drug and alcohol addiction, her parents and therapist decided she needed more help than they could offer.

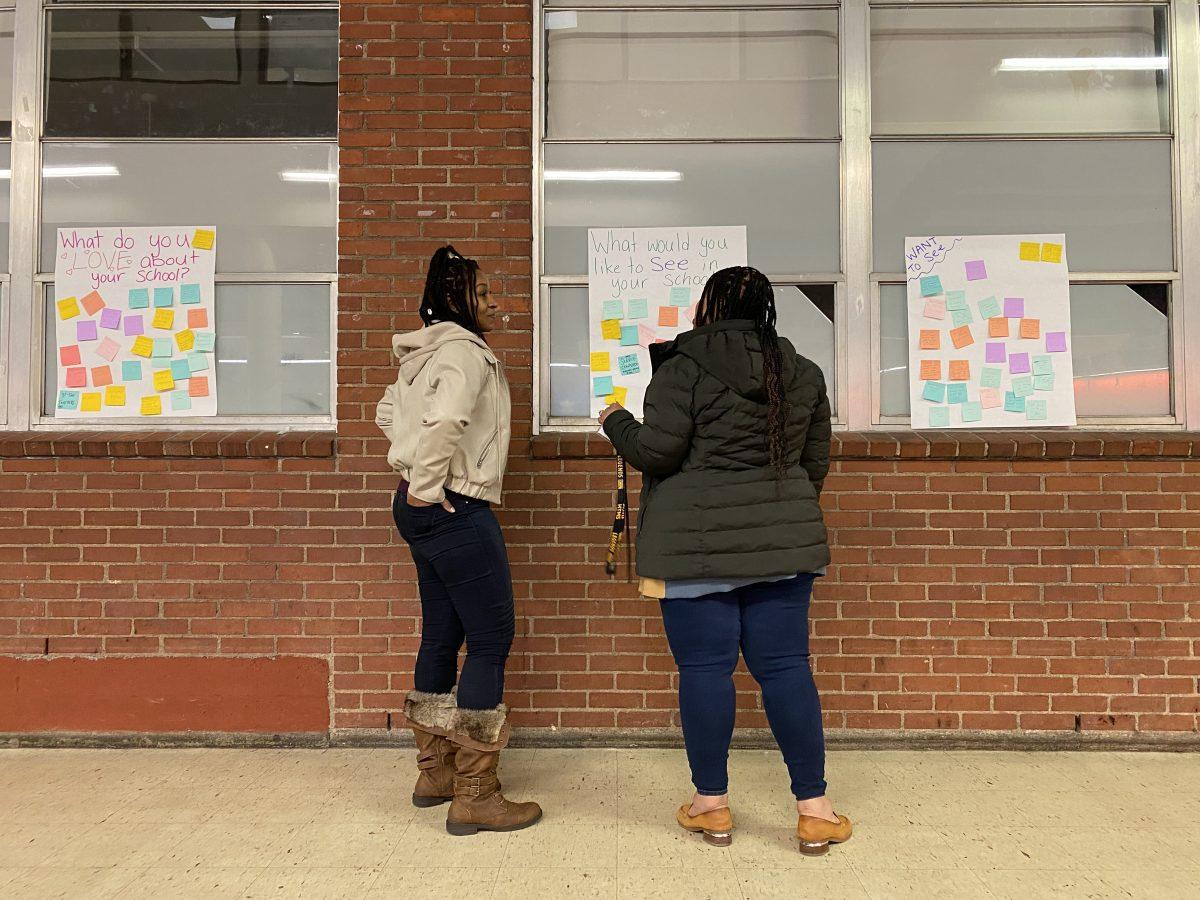

In a recent school-wide student survey by Grant Student Leadership in association with the Red Ribbon Campaign — the largest drug prevention program in the nation — 43.6 percent of the 1020 high school students surveyed reported some frequency of marijuana use, and 53.4 percent reported some frequency of alcohol use.

For the majority of students, this drug and alcohol use is purely social — a staple of weekend parties. When students are under the influence, connecting with friends and socializing can become easier, says Dr. Angelica Morales, a postdoctoral researcher at the Developmental Brain Imaging Lab at Oregon Health and Sciences University.

Others, however, find themselves trapped in addiction. While the introduction to drugs and alcohol can be a shared experience for many high schoolers, frequent use can become the primary way for some students to seek happiness. And for these substance users, addiction can alter perceptions of life without drugs and alcohol. Being sober soon appears dull or unstimulating, making it harder and harder to obtain natural joy.

For students with mental health struggles in particular, drug and alcohol addiction can be even more severe.

Mental illnesses such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often make it hard for those affected to find contentment with their lives and cope with daily issues. “(Mental illnesses) impact someone’s ability to cope at a very young age, and then when they use substances for the first time, they say, ‘Oh my god, I actually feel relief from all the pain,’” says Daren Ford, a mental health provider and licensed clinical social worker with the Counseling Services of Portland.

While national data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services showed a slow decline in adolescent substance use — alcohol use decreased to 33 percent in 2015 from 35 percent in 2013 — the numbers at Grant High School tell a different story. When moving through the halls of Grant, almost every other person that passes has a story that involves personal drug and alcohol use, according to the survey done by Grant Student Leadership.

With students like S, however, drug use paired with mental illness is often detrimental to personal and real-world happiness.

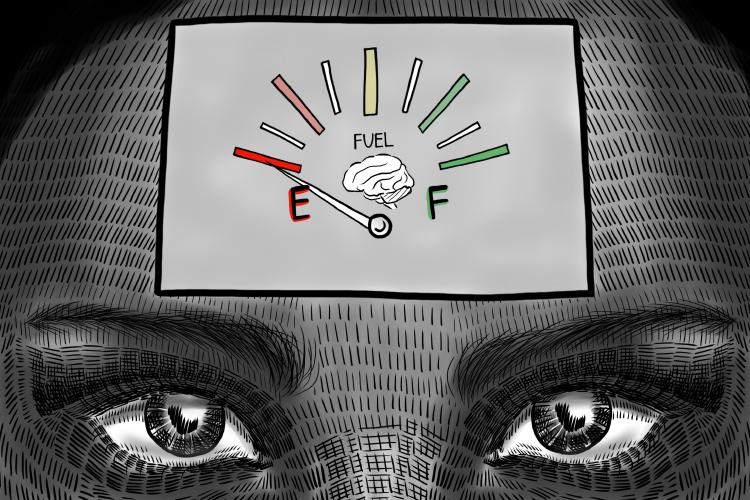

“If you’re already depressed, drugs will just make (mental illness) worse,” says S. “Your brain gets used to how it feels when you’re really, really happy, so when you’re not extremely happy, then you’re like, ‘oh, this sucks.’”

. . .

For many students, transitioning to high school amounts to significant social pressures.

Some students find that these pressures are alleviated through drugs and alcohol; the physical relaxation and confidence boost that is associated with drug use can make it easier to find new friends.

For R, a sophomore at Grant, his first time smoking marijuana was an effort to fit in. Since he was the first of his friend group to try the drug, he thought that it would make him similar to more experienced high schoolers who were already involved in drugs and alcohol.

This pressure isn’t uncommon at Grant and other high schools. “Some kids think that drinking alcohol will make them more popular or talkative or more fun, and those expectations sometimes drive them to drink,” says Morales.

This often occurs at weekend parties where teenagers from across Portland gather to socialize and consume drugs and alcohol. “For me and my friends, (drugs and alcohol) are a party thing, and we’ll do it out, never alone,” says R. “It’s more of a fun thing, meeting other people.”

R says that while his initial introduction to drugs and alcohol was based on influences from the media and an effort to appear cool, later use was due to a desire for the “feel good” effects. As a high school athlete, R found that smoking marijuana was a way to relax his body after a strenuous workout.

The majority of students at Grant who use drugs and alcohol find it to be secondary to other focuses. Drugs and alcohol can be a way to socialize and unwind, and most see it as simply that. For some students, however, the effects of drugs and alcohol are devastating.

S’s experience with drugs and alcohol started out like most: smoking and drinking with her friends. She says she was curious about the effects of intoxicants and wanted to have new experiences with her peers. In addition, she had experienced difficulties making new friends throughout middle school. Going into freshman year she knew that the “drug community” was a quick and easy way to establish a friend group.

After realizing that she enjoyed the feeling of being under the influence of drugs and alcohol, S’s desire for intoxicants became insatiable. “It was a slow increase at first, and the summer after freshman year it was every single day, multiple times a day,” says S.

As S’s marijuana use increased, her sensitivity to the drug went down. S realized that she no longer felt the same effects while high. Her attachment to the euphoria of drugs and alcohol, however, continued. “It was like, ‘Oh, I know what weed feels like, what does acid feel like? What does cocaine feel like? What does Percocet feel like? What does Adderall feel like?’” she says.

While some substance addictions may begin due to curiosity and excitement about the effects of drugs and alcohol, people soon find themselves needing the drugs in order to feel normal, says Dr. Morales. “If you become addicted or dependent, your brain will become rewired so that you need the drug in order to feel as cognitively sharp as you are normally,” she says.

S began to experiment on her own, breaking away from using drugs and alcohol with her friends and instead using them alone to get her fix. “I was seeking the thrill of being high for the first time again,” says S. But she soon found herself struggling with addiction.

While drug and alcohol addiction is severe for anyone, the problem is intensified for people with mental illnesses, as using becomes an escape from real-world problems that they are dealing with.

Not long before she began using drugs and alcohol, S was formally diagnosed with anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder. As these mental illnesses progressed, S made frequent visits to psychiatric wards and hospitals, but returned each time with little improvement.

Aside from visits to the hospital, S attempted to handle her mental illnesses by using drugs and alcohol to bring temporary happiness. “I was suicidal, depressed and really anxious,” she says. “I didn’t want to live anymore. But I was like, ‘Okay, (drugs) make me feel okay for a while.’ It brought me happiness short term, and it was a thing that I felt like I had to do to be happy.”

According to Dr. Morales, dual-diagnosis adolescents usually choose to use drugs and alcohol as an alternative to conventional treatment. “As opposed to going to a doctor to get prescriptions or going to a therapist to help them with whatever is bothering them, they may try to self-medicate with drugs and alcohol,” she says.

Ford also says that drug and alcohol addiction is more common for those with mental illnesses because unlike those without, life sometimes doesn’t seem as worthwhile.

For S, multiple instances of sexual assault throughout her elementary and high school years led to PTSD — a mental disorder that often occurs as a result of a traumatic experience. She was constantly on edge, fearing that she would relive the events. For her, smoking marijuana became a way to calm herself down and give her a short break from the PTSD. “I was just running through constant possibilities,” says S. “Then I would smoke, or I would drink, or I would do acid or something, and it would just calm me down, and I’d be fine.”

With the majority of substance addiction cases, there is an underlying issue of trauma that contributes to the use. “For someone with addiction, trauma is always going to be the expectation, not the exception,” says Ford. “Usually as a kid, (addicts) have had abuse, they’ve been neglected, they’ve been taken away from their homes, their parents have been incarcerated.”

For Grant freshman K, a break-up with his girlfriend gave him a sense of emptiness, one that he thought could be filled with drugs and alcohol. “I was in a relationship with this girl for a year and a half and then we broke up, and then I started doing drugs every day … and now if you name a drug, I’ve probably done it,” he says. “A lot of it was out of despair.”

Even if a high schooler decides to attempt sobriety, withdrawal often makes these efforts extremely difficult. During S’s multiple attempts to quit her use, prolonged time without drugs and alcohol caused mood swings and agitation, and she felt herself becoming angrier towards those around her. S would constantly feel the need to get high, and finding drugs became her first priority.

At this point, S believed that her only way to achieve happiness was through drugs and alcohol. As her brain had become rewired to the effects of drugs, things that previously brought her joy while she was sober — like spending time with friends and playing board games — no longer had the same effect.

“Your sense of happiness is completely skewed,” S says. “What normally would make you happy … is just the most boring thing in the world to you because your brain isn’t stimulated to the extent that you’re used to.”

This altered sense of real-world happiness isn’t singular to S. For many people suffering from substance abuse and addiction, a normal life without drugs and alcohol can seem dull.

For K, his goal is to find happiness in a life free of substance addiction. Currently, however, daily life doesn’t bring him the joy that it used to. “A lot of the things that I found joy in, like music and I mean, just (messing) around with my friends, I didn’t find fun anymore,” he says. “I want to be successful, I want to be happy with what I do. I don’t want to be relying on something that only makes me happy when I do it.”

After nearly two years of dipping in and out of drug and alcohol addiction, S became involved in dialectical behavior therapy — a cognitive behavioral therapy that helps people recognize and understand the emotions they are experiencing — and attended a rehabilitation center in Gladstone, Ore. at the advice of her parents and psychiatrist. During her time in rehabilitation, S found that she was able to reevaluate her life and look towards a more positive future.

With this change in thinking, S has begun to consistently attend school. “I was off drugs for 60 days, and I started to realize that I had skipped school almost every day during sophomore year and I might not graduate,” she says. “At the beginning of the year this year I was still doing a lot of drugs but I was also going to my classes. I needed to make sure I graduated. Now, I have pretty good grades — a 3.4 (GPA) — and I’m going to graduate on time.”

While withdrawals and cravings have made it difficult, S’s attempt to quit drugs and alcohol has lasted for almost two and a half months.

With this decrease in drug use, S’s mental health issues have reduced and stabilized. Three years of therapy and finding the right medication have shifted S’s mindset to focus on the positives of a life free of addiction. She no longer feels the need to turn to drugs and alcohol in order to find happiness.

Drug addiction, as S has realized, is not a death sentence. “Our bodies are incredibly resilient, our brain is incredibly resilient, and addiction is one of the few medical diseases that is 100% curable,” says Ford. “You can completely bounce back.”

Still, it is often hard for many addicts to visualize a life free of substance addiction; the effects of using often hinders the adolescent brain’s ability to see the dangers of drugs and alcohol, says Ford. During the worst points of S’s addiction, even a life past high school seemed unlikely. “If you asked me a year and a half, two years ago if I thought I was gonna be alive right now, I would be like, ‘No, there’s no way, I’m definitely gonna be dead by now,’” says S.

But as Ford points out, when adolescents can better analyze the effects of their addiction, the improvement becomes exponential. “Once they realize, ‘I’ve been using this substance to replace my happiness,’ and they realize that there are other ways that they can do it that are healthier, better and that doesn’t come with a lot of shame, it’s transformative,” he says.

Now that S has recognized that the happiness she got from drugs and alcohol was artificial, she has started to find healthier and more fulfilling support systems. A new group of friends who abstain from using, rehabilitation, and time away from drugs and alcohol have shown her that a future with real-world, substance-free happiness is entirely achievable.

“With my perception of happiness, I used to think about things in immediate and short-term,” says S. “I couldn’t handle the feeling of depression, so I would just gravitate towards drugs because it was an immediate fix … In the past, I was setting myself up for failure, but recently I’ve been setting myself up for success … I feel genuine, and trusted and … happy.”