As her mom’s car pulls up in front of Open Signal, a media arts center in Northeast Portland, Mito Smith struggles to contain her excitement — the day that she has awaited for weeks is finally here. Smith and her friends move directly to the front of the line that snakes out of the building, sliding through the doorway and heading straight to the separate room where the gallery is being held.

Displayed on the walls and projected on screens is work from young, local artists. Smith’s eyes are drawn to a cluster of familiar pieces tacked to one of the walls. She walks over to them, overcome with a feeling of pride at seeing the display of the drawings and paintings she’d worked so hard on.

As her friends split off to wander around the gallery, Smith notices several people taking photos of her artwork. Some smile brightly, while others stare at the paintings intently, trying to decipher their meaning. As she sees the wonder in their eyes, Smith knows that her art has made an impact on the lives of strangers.

Smith has been an artist her whole life, filling up coloring books and later creating her own sketches. However, at a young age, Smith had found herself drawing what other people liked in order to fit in, instead of creating art that spoke to her. In middle school, Smith was harassed by both catcallers and her classmates.

After hearing the students at Grant speak with conviction about the inequalities in the world, Smith became very passionate about speaking up in her own way. For Smith, art is not only a method of self-expression but a language. It helps others understand her own struggles and those of many others. “I want to help the world around me, or somewhat be an activist using my art,” says Smith.

Discovering this has helped her grow from someone who was afraid to share her art with classmates to an artist whose work has been displayed in a gallery. Not only was seeing her art on display a source of great pride for Smith, but it made her realize that she wants to produce more work that can touch people’s lives. She’s ready to make an impact, to elicit empathy in others and speak up for what she believes through the medium that she knows best: quick sketches on scratch paper and detailed paintings that cover her walls.

. . .

Smith was born on December 4, 2001. When she was very young, Smith was dramatic and full of endless energy. She would often misbehave, sneaking bugs into her house or pouring soap onto the floor. As a child, Smith didn’t watch television or have electronics to play on, so she found other ways to entertain herself, turning to art as an outlet to release her energy in a positive way.

Smith drew on every surface that she could, scribbling on the walls with crayon and even drawing on her father’s car with chalk.

Smith’s family quickly noticed her love for art, and her mother, Nobue Smith, began to take her on monthly trips to the art museum. Smith never got tired of looking at the art on the walls, but she preferred creating her own work. “The thing I looked forward to the most was being able to do some crafts down in the basement with my mom,” says Smith.

By the time she was 5, Smith had outgrown scribbling and coloring books and began to copy every picture she could get her hands on. Whether they were from magazines or the pamphlets she snagged from the stacks in the Portland Art Museum, she worked to make her shapes look as close to the photos as possible.

Smith kept drawing throughout elementary school. “(I drew) on classwork, whenever I got bored I would start doodling,” she says.

“She would bring pictures home that she drew in grade school and then follow up on those pictures when she got home, trying to improve on them,” Smith’s father, Dennis Smith, remembers.

With practice, Smith’s cartoon drawings shifted to have more life-like proportions over the course of elementary school.

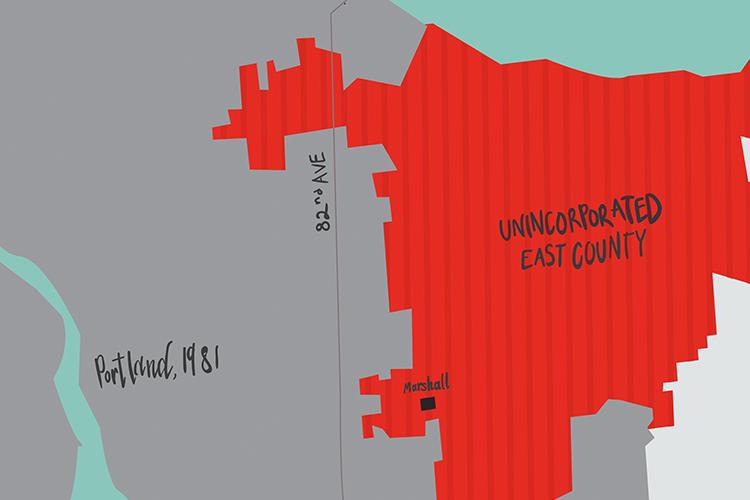

Despite her talent for art, Smith kept it to herself in middle school. Smith already stuck out enough, being the only half-black, half-Japanese student she knew of at Mount Tabor Middle School. “Kids would separate into their own little groups,” says Smith. “I’d be too black for the Asian kids, and I’d be too Asian for the black kids.”

In Physical Education, classmates asked her why she wasn’t good at basketball, confused that she didn’t fit into the stereotype of African-Americans playing the sport. “Kids touched my hair like I was not a person, not even asking, just grabbing it,” says Smith.

Smith wasn’t safe from harassment outside of school, either. Whether it was being followed by strangers or shouted at from men in passing cars, Smith had experienced so much catcalling by 13 that she believed it was the norm.

The summer between sixth and seventh grade, two men approached her and asked for her phone number while she was babysitting her 6-year-old neighbor in a park. When she refused, they continued to follow her around the park for the next two hours. “No one really noticed,” says Smith. “I would just keep walking (and) ignore them.”

It wasn’t until she was catcalled in front of her friends that she learned it wasn’t okay. Before, Smith didn’t know just how serious it was. “That’s when I realized … that’s not something that should happen,” Smith says, “It’s really scary to think 13-year-old me was walking to a library and someone shouted out a car window, or 13-year-old me was at a park and got followed.”

As the beginning of freshman year approached, Smith found herself unable to relate to her friends’ nerves about starting high school; she was just glad to finally leave middle school behind.

The hallways were full of new faces, and Smith quickly noticed that the loudest voices were standing up for what they believed in. She was struck by how her views aligned with those of the speakers at the assemblies and the members of the Black Student Union (BSU), and she began to attend as many BSU meetings as she could. “I kind of got a lot of … enlightenment from them,” says Smith. She also joined Grant track and cheer.

Smith remembers being especially moved by one of the dances that was performed at Grantasia. Their slow hip-hop routine addressed police brutality and the unjust violence directed towards the black community. “People are so brave, and the people that discover their passions at a younger age, it’s just so empowering to watch them pursue it,” Smith says.

Thinking about the Grant students who spoke out against prejudice and ignorance, Smith knew that she had to speak up in her own way. Turning to what she knew best, she picked up her paintbrush — this time with a purpose.

Smooth brushstrokes flowed out from her hand, forming a girl with an afro full of flowers, adding tears streaming down the girl’s cheeks. A single hand pulled some of them away, leaving a bleak fog in their place.

As Smith painted, she remembered the way that people would grab her curls without permission or tell her that her hair would look better straightened. “I see that happen to other people and myself, and I try to focus on the voice that people don’t have,” she says. “They want to say something, but they don’t know how to say it.”

To Smith, the painting represented how people try to rip the beauty out of others and take away their positive energy. She hoped that this piece would impact people who have had similar experiences.

Her brushstrokes formed women with afros, mothers cradling their children and oceans filled with plastic. Each piece communicated a powerful message through the colors and lines.

Smith’s desire to share her art heightened when she was able to display her work in a gallery through an art class later in her freshman year. Two days a week, Smith would ride the bus to the Pearl District after school to learn how to make digital art in the Wacom building. When Smith learned that students in the class would be given an opportunity to showcase their art in a gallery, she readily accepted. She selected a few pieces that she had created at home, as well as pieces she had created in the class. “I was super excited, even a week before, even while working on my pieces,” says Smith.

She painted a woman relaxing in water, fish swimming around her hair, and a digital piece of a woman with an afro and the venus symbol behind her. Smith chose these and several other works to hang in the gallery, all displaying their own meanings through images of nature and women of color.

All of her work in preparation for the showcase became worth it when Smith saw how it impacted the strangers in the gallery. “It was nice to have people looking at the purest thing I could give,” she says. Smith knew the emotions and concerns for the world that she had poured into these pieces had reached the people in the gallery, and she wanted her artwork to reach an even larger audience.

Now that Smith is more aware of the issues and injustices in the world, she’s eager to do what she can to support important causes. Recently, Smith attended Portland Pride Parade and joined tens of thousands of protesters at the Women’s March, holding a sign on which she had drawn four women, the venus symbol, a rainbow and a fist. “I owe it to all the other people in the past that have struggled and didn’t have a chance to speak up,” says Smith. “Whenever I do have a chance (to speak up), I’ll take it.”

Whether it’s in a gallery or not, Smith wants her artwork to be seen. “I want it to speak to people, even if it isn’t super happy, if it’s super harsh-looking or super sad,” she says. “If it can make you sad, that’s one of my goals … to be able to touch people.”

Empowered by the way that Grant students raised their voices, Smith finally finds herself able to stand up to catcallers. “Now, if someone catcalls, I’ll glare back,” says Smith.

Though Smith is certain that she wants to make a difference in the world through art, she knows how difficult it is to be a solo artist. “I love doing art, but if that becomes a chore, if that becomes painful to the point that I can’t support myself, then that’s just something that I don’t want,” she says.

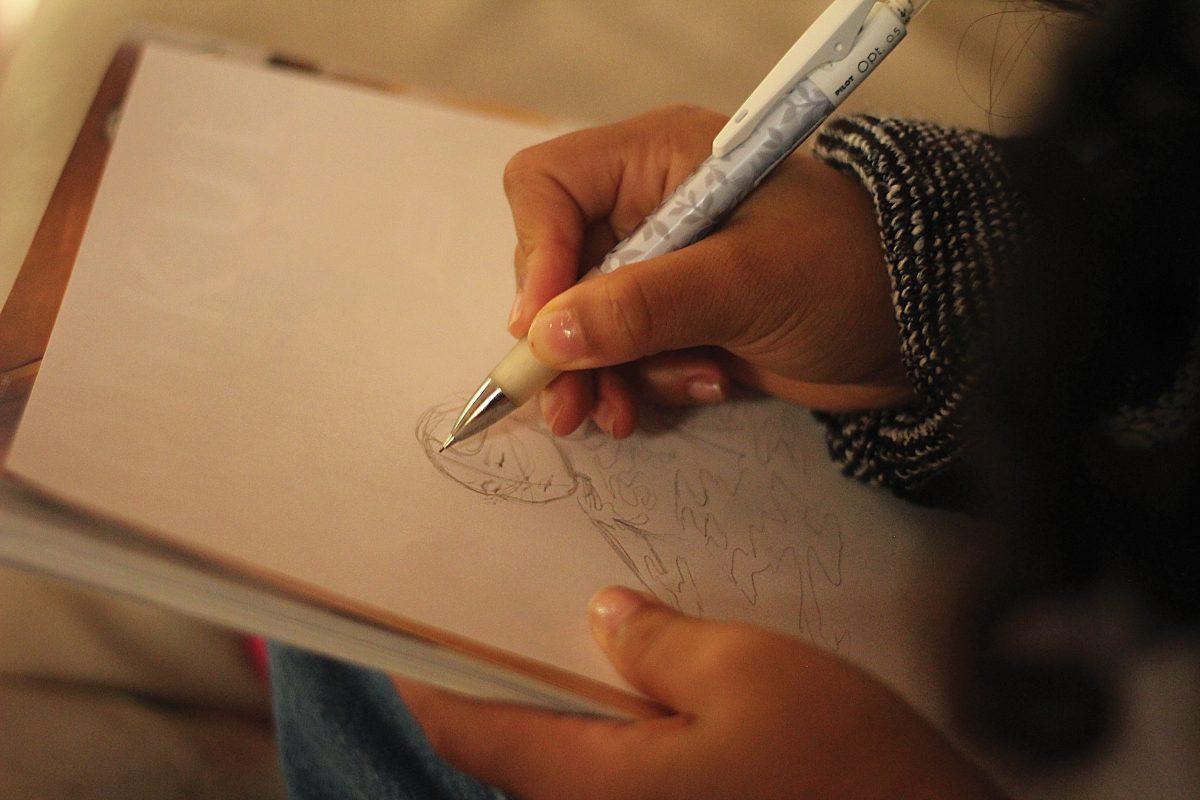

On October 4, Smith suffered a concussion after she was dropped at cheer practice. Weeks later, she still struggled to read and concentrate, and her vision was out of focus. One night when she was having an especially difficult time working on her homework, Smith set it aside and began to sketch on a piece of scratch paper.

The lines left her pencil effortlessly, all of her built-up frustration flooding onto the page. A tangle of hands formed, all reaching for something but not quite succeeding. A brain-shaped flower crumbled in the corner of the paper. In that moment, Smith didn’t need words to express her feelings. Her art was enough.