Sam Harquail was waiting in the lobby of Matt Dishman Community Center after a high school swim meet when he started to feel his body grow heavy.

A wave of exhaustion washed over him as he struggled to even lift the cup of apple juice he was holding. Within seconds, he was lying on the floor, fully conscious but shaking uncontrollably.

Soon, Harquail was laying face up on a stretcher, rolled into an ambulance and rushed to the hospital.

“It’s etched in my memory forever. It was traumatic. We didn’t know what was going on,” says Kristin Harquail, Sam Harquail’s mother, of the event.

Harquail’s passion for swimming started young. After years of dedication under his belt, it came as no surprise to his family and peers that he was ranked 16th in the country after Nationals his junior year in high school.

But after full body convulsions in 2015, Harquail couldn’t even get out of bed, let alone swim, due to the immense pain he was experiencing. For months, Harquail thought he may never reach the same level again and considered quitting swimming altogether.

But eventually, he worked his way back to the top.

Now, new swimmers on both his club and high school team look to him as an example.

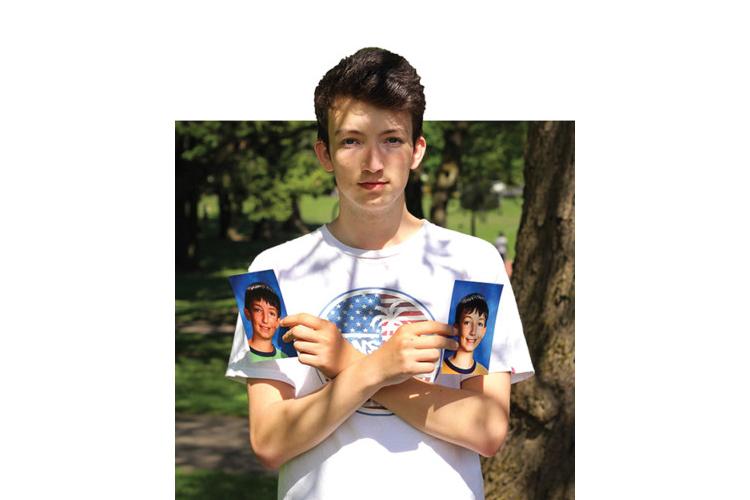

“It is a really humbling feeling,” says Harquail. “I had someone to look up to when I was a young kid, so I am happy and humbled to be the person young swimmers look up to.”

Harquail was born on June 5, 1999, in Portland, to Kristin and Steve Harquail.

Harquail’s first swimming experience, like many children, started when his parents signed him up for swimming lessons at the age of 7. The lessons soon became a passion for Harquail. After he finished them, he and a group of his neighborhood friends joined Grant’s Summer Swim League, a recreational team for beginning swimmers.

On the team, Harquail trained by swimming laps in the Grant pool five days a week for an hour at a time. The training regime took a toll on his other activities, and he eventually had to stop playing soccer and baseball.

Before practice, Harquail would watch the Portland Aquatic Club (PAC) swim. After a while, he began showing up early to analyze their technique. He was left in awe.

At age 13, Harquail was set on joining PAC. But being on a club team was a much bigger committment than he was used to. The team swam longer, practiced more often and competed at a higher level than the recreational team. But Harquail was ready for the challenge.

Harquail excelled on PAC. By eighth grade he had made it to the Oregon State Championship and was competing on the senior team.

After joining, Harquail started swimming faster at every meet. “Those results made me realize that this is what I want to do,” he says.

“I think it’s his willingness to make strong changes in his stroke” says coach Jody Braden of Harquail’s rapid improvement. “He is able to manipulate his body to swim the fastest, and he can do things other kids can’t.”

By pushing himself at practices, Harquail started to gain traction, spending hours at the pool over the weekend. Upon entering freshman year at Grant, Harquail earned a spot on the varsity swim team.

By junior year, Harquail was the fastest swimmer on the team and had set multiple school records.

“I like to leave a mark wherever I go,” says Harquail. “Having those records and the sensation of getting those records just makes me want to go out more and more.”

That same year, Harquail got the chance to race at Nationals in Federal Way, Washington. Over a two day period, he competed in the 100 meter breaststroke and swam alongside decorated athletes like Nathan Adrian and Michael Phelps.

“Nationals was the experience of a lifetime. I got to swim the red carpet of swimming. That was really cool. That was really big for me,” says Harquail.

In 2015, Harquail also qualified for the Speedo Junior Nationals – A national meet that determines the top swimmers in the nation under 18 – which was held in December of 2015. Before traveling to Austin, Texas for the competition, he started spending six days a week in the pool, training three hours at a time to prepare for the competition.

The day before Junior Nationals Harquail prepared himself by shaving his entire body to increase his speed, bathing in ice and eating a carb heavy dinner.

Stepping onto the blocks for his first race, Harquail wasn’t expecting much – he was just happy to be there. But Harquail achieved his personal bests in the 200 meter, 100 meter breaststroke and 200 meter individual medley. He ranked 16th fastest in the nation in the 100 meter breaststroke.

“It makes me feel like all the hard work has finally paid off,” says Harquail. “A lot of times during training, you aren’t getting anywhere, so when you do get tapered and pop a good swim, it feels amazing to find out that put me 16th in the nation.”

He started to gain the attention of several colleges, receiving recruitment emails from around the country, and he started to think about swimming as a potential future for himself

But a week later, everything changed after his convulsions at Matt Dishman Pool.

When he was first admitted to the hospital after the incident, Harquail had trouble sleeping.

“I told (my mom), ‘I’m worried if I go to sleep, I won’t wake up again,’” says Harquail.

The next day doctors had to perform a lumbar puncture on Harquail – a medical procedure done to determine if a patient has meningitis. But the doctors mishandled the procedure, and Harquail started to experience immense pain throughout his lower back and head.

After a full week in the hospital, the doctors diagnosed Harquail with conversion disorder, a neurological disorder caused by stress or an emotional crisis.

His parents and even his pediatrician questioned the diagnosis.

Harquail’s pediatrician told him that she thought he had experienced the spasms because he swam the day after he received the HPV shot – intense exercise after the shot can sometimes lead to dangerous side effects.

While recovering at home, Harquail would seize up at random times throughout the day. The mix of exhaustion and pain made it nearly impossible for him to move. As Harquail slowly got better, resting gave him enough strength to walk around. His first thought was to jump in the pool.

“As long as the doctors allowed it, I wanted to get back in and start rebuilding strength,” says Harquail.

After two weeks of recovery, Harquail was back at Dishman pool, but he could feel that he was significantly slower than at Junior Nationals. His time was nearly a minute slower than before.

His inability to swim as fast as he wanted lowered Harquail’s motivation. As months went by, Harquail went to fewer practices.

Seeing little improvement frustrated Harquail and he lost faith in his ability to improve.

But by the summer of 2016, motivation sparked in Harquail. Junior Nationals was around the corner, and he was determined to reach his best time. He started going to every single practice, training harder than ever.

On December 8, 2016, Harquail flew to San Antonio, Texas for his third Junior Nationals meet. He was nervous but determined to show he was still improving.

At the meet, Harquail just barely qualified for finals.

As Harquail touched the wall during the final race, he looked at the board for his time. He had swam the 100 meter breaststroke in 56.5 seconds, a new personal record.

Although Harquail’s national placement wasn’t as high as the year prior, he was satisfied. “When you’ve gone that long and not improved, even the smallest improvements just make you so happy,” says Harquail. “I think swimming has taught me that you can’t just cruise along in life. You have to work for your goals.”

As a senior on Grant’s swim team and PAC, Harquail is now someone new swimmers look up to, a position he has been striving to achieve since his first time on the blocks.

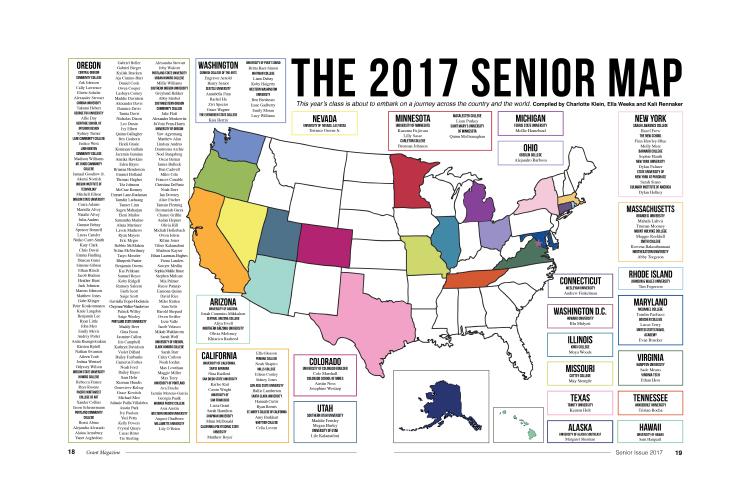

This past February, Harquail participated in the high school districts swim meet, then moved onto state where he took first place. Next year, Harquail will swim for the University of Hawaii.

Through it all, Harquail says his passion for swimming has carried him. The sport has made him who he is.

“I think swimming has built the confidence in myself, and it has made me more comfortable in my body,” says Harquail. “It has not only given me the strength but has opened me up and given me the confidence in what I do.” ◆

Reporter Sydney Jones contributed to this story.