It’s early in the morning on December 29, 2015 in Old Snowmass, Colorado. Senior Cosmos Dart wakes up in his family’s vacation home to his parents, sister and two unfamiliar men surrounding his bed.

Immediately, Dart knew something was wrong.

“They came to my bed, and they told me that they were really worried about me, and they were deciding to send me away to wilderness, to a camp,” Dart remembers.

In only a matter of minutes, Dart was forced to say goodbye to his family, hugging them one last time before the two men showed him to the car outside.

From Old Snowmass, Colorado, to San Rafael Swell, Utah, they drove six hours; all the while Dart’s worry intensified. “It was the lowest day of my life … It was very traumatic,” says Dart. But, he says, “(My parents) had to do it. And I’m so glad they did.”

Dart arrived at Elements Wilderness Program, a rehabilitation camp for adolescents struggling with substance abuse and mental health. It would be a week before he would gain any sort of contact with his parents. But his time there was life-changing.

Since he was young, Dart has struggled with depression and mental health issues. When he reached adolescence, he began using drugs to cope with what he was going through.

This is common among high schoolers, with many teens turning to substances like drugs and alcohol during difficult times.

“People can be drawn to things that distract them or make their anxiety or depression feel a little bit better for a short period of time,” says David Kerr, an associate professor of psychology at Oregon State University.

That’s why Dart became part of a growing trend among teens struggling with substance abuse and mental health issues who attend wilderness rehabilitation camps.

Experts say that these rehabilitation camps work because they allow adolescents to be distanced from their home environment and gain more of an understanding of themselves, with the help of onsite mental health professionals.

“When someone’s struggling with their current situation, sometimes it can be helpful to kind of separate from that,” says Adam Eader, the admissions director at New Vision Wilderness, a rehabilitation camp with locations in Bend, Oregon and Grafton, Wisconsin. “Not necessarily ignore (their situation) and run away from it, but just separation.”

At wilderness rehabilitation camps, adolescents spend the entire time outdoors, hiking, building fires and learning survival skills. Simultaneously, they meet with therapists to work through their struggles. Communication with family is minimal.

While initially difficult, the experience was transformative for Dart.

“It taught me to believe in myself and to communicate with others and be transparent,” says Dart. “And more importantly, grow each day and not be afraid of feeling sad.”

Dart was born June 13, 1999, in the small town of Hankins, New York, which Dart recalls as having a population of only a few hundred. Parents Catherine and Will Dart also had a small apartment in lower Manhattan, and they often alternated between the two locations.

The family moved to Portland when Dart was 3 after Catherine Dart found a job as a yoga instructor in the city.

As their new life began in Oregon, Catherine Dart recalls her son’s eagerness to have a sister. When she became pregnant with her second child, Pearl Dart, Catherine Dart remembers thinking, “It was like he called her.”

Growing up in Portland, Dart grew accustomed to alternative educational environments. He attended a small pre-school located in a friend’s backyard. From there, Dart attended Metropolitan Learning Center, a K-12 school that focuses on personalized learning. MLC provided Dart with a small, tight-knit community of around 500 people among the 13 grade levels.

“There’s just more perspectives,” Dart says of MLC. “It taught me how to learn from my mistakes, but in a way that teaches other people as well.”

In elementary school, Dart considered himself an athletic and adventurous person, constantly playing basketball and going on hikes with his family.

“Cosmos would take me up in front of my parents on the trail, and we would find trees to climb or logs to go over, things that scared me at the time,” Pearl Dart remembers.

Through most of elementary and middle school, life went smoothly for Dart. Then, in February of his eighth grade year, things took a turn. Dart remembers the day his dad came to his school to deliver bad news. “He came up to me, and immediately I knew something was wrong,” remembers Dart.

Will Dart informed his son that his uncle, Paulie, had taken his own life. “I was totally in utter denial, ‘There’s just no way,’” Dart remembers thinking. “I was in denial that something that bad could happen to people who didn’t really deserve it.”

The death stuck with Dart, leaving him in a state of self-reflection. “I think that sparked this depression but also this like anger almost,” he says. “I was really angry at myself … I often blamed myself for it.”

The transition to high school proved difficult for Dart, as his mental health struggles grew, and his uncle’s death held lingering effects. The community at Grant was also strikingly different from that of MLC, as Dart went from a 500 student population to one of 1,500.

Despite this, freshman year went relatively well for Dart, as he got acclimated to the new learning environment and was succeeding in school. He was making friends and kept good grades.

But as sophomore year approached, struggles with friendships arose. Dart says he was cut off from two of his closest friends. And on top of that, one of his best friends was moving out of the state.

The start of the school year also triggered his anxieties with the rigid structure of the days that didn’t fit his learning style.

Later in the school year, the opportunity came for Dart to live in Spain for a semester and attend school there while staying with a family friend. Dart accepted the offer right away, but the experience wasn’t as he expected.

School in Spain was harder than he had anticipated, as Dart struggled keeping up in Spanish. Dart remembers his mind being stuck on life in Portland. Navigating both worlds began taking a toll on him.

It wasn’t long before his parents suggested he come back two months early. Dart agreed, although he remembers that leaving early made him feel like he “failed.”

Coming back to Portland, Dart felt he didn’t have a place in his old friend group.

As summer after his sophomore year began, Dart started smoking marijuana multiple times a week to cope with his depression and distract himself from what he was going through emotionally.

Dart’s experience is similar to many. Samantha Pelkey-Flock, a therapist with Key Counseling in Portland, who specializes in working with adolescents, notes that drugs are commonly used as a coping mechanism. “Their appeal is that they tend to make you feel good, even if that’s only temporarily,” she says. “So if that person is feeling really stressed out, a way for them to get through that is to self-medicate.”

In June, Dart began seeking help by regularly visiting a therapist. “It provided me a place to vent,” recalls Dart.

Once his junior year started, his anxiety only increased. He struggled focusing in school and sometimes had breakdowns and suicidal thoughts. He began skipping class more frequently.

“It’s almost like a freakout, like a breakdown with my suicidal thoughts, but it’s just like, I can’t handle being in this building so I have to leave,” he says. “They were really intense and real.”

For Dart, in-school resources, such as meeting with a counselor, weren’t an adequate option. He says that the privacy protocols of counseling sessions and the limited time in the school day make talking to school counselors difficult.

“It’s just set up in a way that you can’t talk to them, you don’t have any time to discuss anything,” says Dart.

Instead, his parents took him to the doctor, where he was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, or ADHD, a mental health condition that makes focusing difficult. Dart was prescribed Adderall to minimize his symptoms. He soon began abusing Adderall – in addition to other more intense drugs he was prescribed.

“I don’t tell anyone about what I’m doing because I don’t want … people to judge me or just to be labeled as a ‘druggie,’ and I don’t think people would understand,” says Dart.

As the months progressed, things only went downhill. He remembers rarely completing his homework and detaching himself from friends and family.

One night, the negative self-talk and guilt grew intense. Dart remembers the suicidal feelings coming back, even stronger than they were before. He came close to committing suicide. But thinking about his family held him back.

“I started thinking about how … much I would affect my sister and my parents and how horrible I would make their lives,” recalls Dart. “I didn’t want to ruin (Pearl’s) life or scar her for that.”

That night, Dart turned to drugs to distract himself from the pain.

“I realize that I’m just really self conscious, and I don’t feel liked or loved by anyone and how that’s not really anyone else’s fault but mine,” says Dart. “It was scary how intense it was.”

Only a few nights later, Dart ventured downstairs to grab his phone to play music and help him fall asleep, though household rules require his phone to be downstairs at night. When his dad heard his son in the kitchen, the two began getting into a yelling match. Out of anger, Dart remembers pushing his dad away, with force.

“I’ve never become physical with him,” says Dart, recalling that moment vividly. “I see myself in that moment and how much of a monster I am.”

Dart remembers how everything seemed to come crashing down. Before long, he was telling his parents everything he had been feeling.

For Catherine and Will Dart, it became clear that they needed to try new resources. They did some research and looked into alternative therapy methods, leading them to wilderness rehabilitation camps.

“It just seemed to match the entire picture, being outdoors, being able to not be surrounded by everything that was going on here,” recalls Will Dart.

His parents didn’t tell Dart about their idea right away. Instead, they went on their annual Christmas trip to Colorado to visit family as planned. Dart remembers the initial part of the trip feeling tense because he wanted to stay back in Portland with his friends.

Then, one night on the trip, Dart was awakened by his family and two men from the program. After informing Dart about their plan to send him to Elements Wilderness Program, they said their final goodbyes.

“I just remember being completely fine with it because he was in an awful place,” says Pearl Dart.

Dart then made his six hour journey from Colorado to Utah. The first several days at Elements were difficult and Dart was on self harm watch. He couldn’t talk to anyone but the counselors.

Initially, Dart resented being forced to attend a camp when it wasn’t his own choice. He remembers being angry that he was forced to undergo intense therapy and had to live life without modern technology.

That all began to change several nights in, when he was eating dinner – mac and cheese with sausage – while sitting around a fire with several other campers.

“I felt like these people cared about me,” recalls Dart. “That night it made me realize that maybe I do need to work on some stuff, and even if I hate it right now, and I’m scared, and even if I don’t agree that I’m here, it’s gonna benefit me.”

As part of the camp, parents are required to write letters to their kids outlining why they sent them away. Catherine Dart recalls this experience clearly. “We had to be honest and perfectly candid with Cosmos. To actually write it out, it was hard,” she says.

Given it was the middle of winter, Dart recalls the conditions at the camp being harsh. He rarely showered to avoid being exposed to the cold temperatures.

Most days at the camp consisted of helping with camp chores –pitching tarps, cooking meals and starting fires – as well as reading, hiking and going through therapy, all in the wilderness and with little to no contact with family or friends.

“It made me feel like I … hadn’t seen humanity in like years. It was bizarre,” says Dart.

Experts say that this separation is what makes wilderness camps so beneficial.

“For some clients, that home therapy … it’s not working, because they can’t get away from some of those conflicts or problems that they’re having at home. That’s what wilderness does, is it takes you out of that,” says Eader. “It’s remote.”

Dart also spent a lot of time meeting with a therapist. Many of the other camp attendants also struggled with substance abuse, and Dart discussed that, as well as his mental health, with onsite counselors.

“They really made us talk,” recalls Dart.

As Dart entered his seventh week at camp, he received another letter from his parents, discussing their plans for him after he was done at Elements. They had decided to send him to a residential treatment center near Salt Lake City.

“I was so sad and angry and depleted,” says Dart. “I think I cried because … you’re so close to going home. It was really hard.”

On February 29, Dart’s parents came and picked him up from Elements. Saying goodbye to staff members and peers was difficult. “They had been my family, you know, not even my friends, my family,” he says. “They had been there for the most intense thing I had ever done in my life … I pretty much owed everything to all of them.”

Then, on March 1, Dart and his family pulled up to the residential treatment center at Gateway Academy, in Draper, a suburb of Salt Lake City, Utah.

Life at Gateway Academy wasn’t as Dart had expected.

“They treated us like we were crazy inmates, like we couldn’t talk to each other, and there always had to be a staff in earshot, we couldn’t listen to music, couldn’t go in a room alone, couldn’t go off campus,” says Dart. “The schedule was very strict. And they were trying to teach us that the system is always in control.”

The therapy was different too, as his therapist often pressured him to answer his questions.

Dart left after three and a half months. With the price of Gateway adding up, his parents couldn’t afford it much longer, and the normal school year would be wrapping up soon. It was a moment he’d thought about for six months since he first left Colorado in late December.

“I was nervous to go back, but I was so excited,” Dart says.

When he returned home, life was far from normal. Dart was limited to hanging out with only certain friends, and he couldn’t have sleepovers at his friends’ houses. He also had to get a job.

On top of that, his relationships with his friends didn’t pick up where they left off.

“My friends – it was still a struggle, they just treated me like a drug addict. They didn’t think I changed – trying to keep me away from people smoking, like, ‘Are you sure it’s okay? Are you okay?’ And treating me like I’m a little kid … it’s kind of demoralizing,” says Dart. “They treated me like I was stupid, like I didn’t know what was good for myself, even after I had gone through all this internal learning.”

Going back to school was an even bigger challenge. He’d gotten so used to being outside of the structure of public school that when he came back, his old anxieties racked him.

Dart recognizes now that he doesn’t need drugs to numb his feelings. But many people continue to label him as a “drug addict,” he says.

Looking back on his time at Elements, Dart says it was a positive experience, as he’s seen a self-transformation. “Acknowledging my sadness and my downs, not having to live for the ups, but live for every single moment,” says Dart.

He wishes for everyone who struggles with drug abuse to experience a wilderness rehabilitation camp at some point in their life, but recognizes that this experience isn’t available to most.

Given the cost of wilderness rehabilitation camps – many being over $400 per day – some students who deal with depression, anxiety and drug use can be left without adequate support systems. Pelkey-Flock notes the importance of making these resources available for all students. “I think it needs to be a priority for schools to figure out how to help lower-income students as well,” she says.

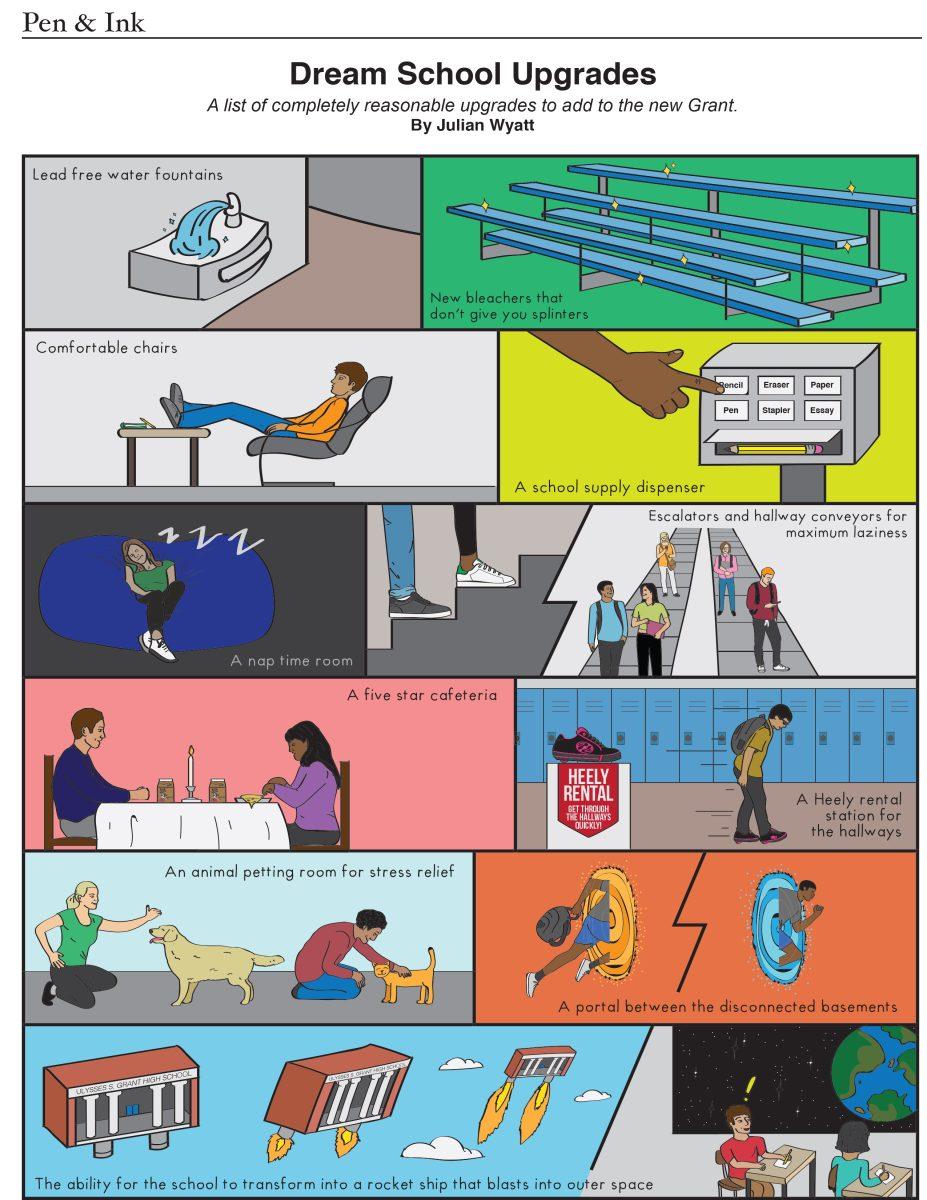

Dart says the in-school resources at Grant for dealing with mental health or drug-related issues can be improved: “In order to even bring therapy or communication into the picture, they have to realize that the structure they’re working with is blocking out all of the communication,” he says.

As Dart looks to his future, he hopes to travel to Europe and India over the course of a year before he goes back to school. Right now, he says, he is focused on graduating.

For Dart, his struggles with mental health still remain in play, and school and relationships continue to bring on their own stresses. But Dart says his rehabilitation experiences have helped him find ways to cope with his anxieties.

“I’ve learned more in the last year than I have in the last five,” he says. “Wilderness taught me to believe in myself.” ◆