I, like hundreds of other students at Grant, and roughly 248 million people around the country, own a smartphone. Every day I wake up to its alarm. It is the first sound that greets me in the morning and it is the last thing I see before bed. Whenever a dull moment arises, whether it’s a lecture in my math class or a stroll through the halls, I reach for it. Even when I’m angry or anxious about an upcoming project, I turn to my phone and social media to calm me.

Every buzz, ring, notification, and phone call draws me closer to that angelic rectangle.

For most of my cellphone-bearing life, I didn’t think this was an issue. When I first received an iPhone – as a Christmas present my freshman year – I laid in my bed and scrolled through it for hours, not looking up once. I was given access to an entirely new world, one filled with endless games, virtual friends and fail videos. I didn’t look back.

But as I, and all of my peers, have fallen deeper into the realm of technology use, I’ve noticed some increasingly unhealthy habits. I stay up late when I’m around my phone or laptop, the endless stream of distractions keeping me up even when I know I should sleep. I use it when I want to be engaged in a conversation with a friend, my mother or my girlfriend. I grow anxious when I am away from it because my body feels like it’s missing something. And I text and scroll on my phone while driving even though it has been proven to be nearly six times more dangerous than driving while drunk. Nearly 21 percent of fatal car accidents involving teens are caused by cellphone use.

I’ve been putting my own mental and physical health at risk just so I can use my phone and I’m struggling to understand exactly how it got this bad. If this were cigarettes, alcohol or gambling that I had just described, the evidence would be clear. I would be addicted. But when it comes to phone and technology use, the research simply hasn’t had time to catch up with the growing number of people using technology. For now, there is no official diagnosis for phone or technology addiction and for the most part, people have to learn to handle their dependence on their own.

I decided to test my own obsession by attempting to go without my phone for an entire week. I was set on showing that I could forget about it if I needed to. When I first handed it off to my mother on Monday morning as she dropped me off for school, I walked 15 steps away from the car before reaching into my pocket to grab my phone. My stomach dropped and my breath caught. My initial reaction was that I’d lost my phone, my mind had already forgotten about my goal. In the next hour, I reached for it another five times.

The next few days were an odd mix of peace and quiet and stressing over my missing phone. For the first time in months, my mind wasn’t always turning towards another distraction. On my bus ride home, I would just sit and think – no music, no games, no Snapchat, just me and my mind. And for the most part, I was more focused. I still had my laptop available but all the media I use, including Netflix, Youtube, Facebook, and Instagram, were blocked. I wrote and edited photos on my computer and occasionally browsed the news.

But the harsh reality was that I still needed to be plugged in. By the fourth day, I was walking through the Grant halls with my laptop open, frantically sending texts to people I needed to reach. I couldn’t go on. By Friday morning I had given up.

It’s obvious that my phone controls me, but it’s not surprising. My brain, like yours, feeds off of rewards or small bursts of dopamine that fuel our urges. When we get a buzz on our phone alerting us that someone or something has given us some attention, we get a little whiff of dopamine in our brains. Nothing compared to actual substances but the same reaction is in effect. It makes us hooked.

The social media apps that we use every day are specifically designed to feed off of that exact process in our brains and make us check our phones as frequently as possible. The more we go back, the more that advertisers and marketing companies get screen time, and social media companies raise their profits. Facebook’s continuous scroll, Instagram’s explore pages, streaks on Snapchat – they all keep us coming back.

I have bought into that addictive system of social media and apps. Most of the time I spend on my phone is unwarranted and I often feel bad about myself afterward, whether it’s because I get called out by a teacher, ignore a conversation with a friend or distract myself for hours from working on homework. It is rarely a welcoming experience.

This isn’t to say that my technology is all bad. I have used my phone and laptop to create stories using audio software, to record my band at live shows and to have face to face conversations with friends living across the country. Technology has done incredible things for me.

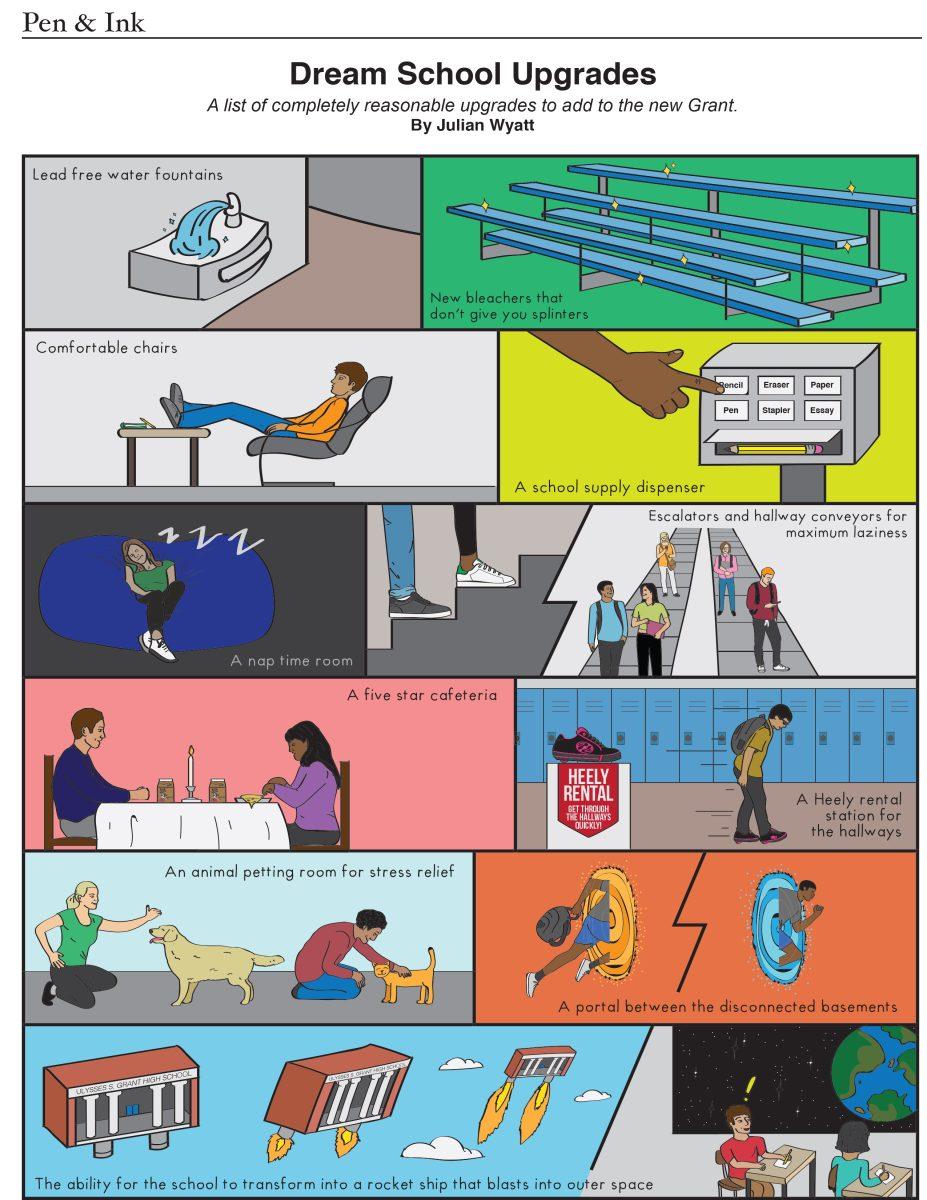

At Grant, in the last few years alone, an audio engineering, digital media, computer programming, and Android innovation class have been added to the curriculum, among other technology-based programs. It seems that technology is essential for the future of our economy.

It is for that reason that the idea of stepping away from it is so frightening. Technology feels essential to my existence and my interests. Getting rid of my laptop and phone is taking away not just my bad habits of social media but also my passions in audio and media. At least it feels that way.

It’s hard to decipher the difference between abusing my screen time and using it to better myself. All I know is that I spend an excessive amount of time looking at a screen. If I continued the same phone habits I’ve had the last few months – two hours a day on my phone and roughly another two hours on my laptop – for the rest of my life, dying at the age of 90, I would spend over ten nonstop years looking at a screen. As an 18-year-old, that’s more than half my life. Think about that.

Ten years of social media, short videos, memes, holographs and virtual reality (who knows what’s next?). And if my technology use increases, which judging by the pace of things right now is very likely, then I’m in for even more.

What I have realized is that my phone hasn’t made me any happier, it hasn’t filled a void in my life that needed to be filled. It has only distracted me from any unhappiness or dissatisfaction that I might have, instead of allowing me to approach it head-on.

But even as I sit here now, writing a piece denouncing excessive technology use, I find myself in a room surrounded by dozens of other people absorbed in their phones and laptops and I too, as troubled and confused as I am about technology use, am still lost in a screen that I have yet to find an escape from. ◆