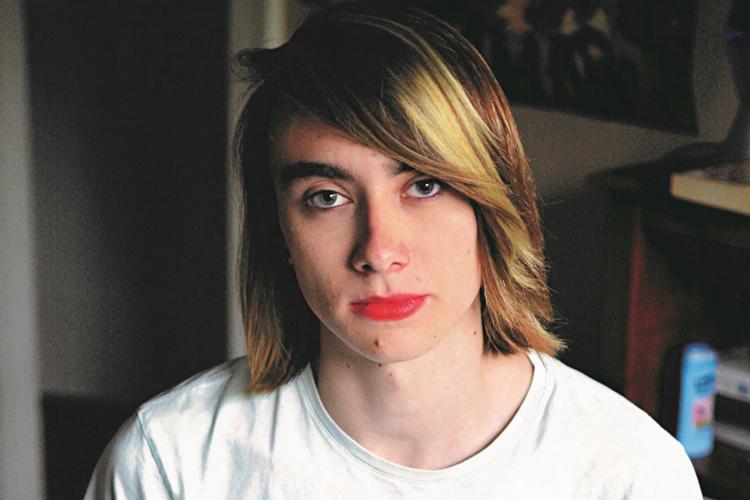

[aesop_image imgwidth=”100%” img=”https://grantmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/grace-thumb-1.jpg” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”The Kowitch household is very positive and always tries to come together to work around difficulties. Art Kowitch says, “Grace is very optimistic. When we are grappling with something that happened she will tell us not to worry and ‘look on the brightside.’”” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off”]

On a recent Wednesday, senior Grace Kowitch sits in her Economics class taking steady notes about the dangers of credit card debt as her teacher, Dan Anderson, leads the class. Kowitch, who’s wearing her signature cheetah print leggings, a ruffled t-shirt and high heels, flips her hair away from her face and fiddles with her bracelet.

She is the only student in the class, or in any general education class in the school, with Down syndrome. But the congenital disorder that causes intellectual impairment and physical abnormalities hasn’t slowed Kowitch down. And she doesn’t take her education lightly.

“I get to see all of my friends, get to meet other people I don’t know really,” Kowitch says. “It is fun to reach out and be part of other real classes.”

Kowitch has taken almost all of her high school classes outside of the special education program and is more active in the school community than most high school students. Dance, choir, theater, swim team, basketball – nothing is out of Kowitch’s comfort zone. She even mentors a younger student with Down syndrome on their speech and social skills.

But Kowitch is an anomaly among other students with Down syndrome in the school and around the country. Inclusion of special needs students in general education classes is lacking despite the evidence that students gain better social and academic skills from it.

Having students with Down syndrome in general education enables students with special needs to learn higher material and helps combat negative stereotypes held against people with mental and physical disabilities.

Grant special education teacher, Rina Shriki, says, “It’s beneficial for both students involved to be able to work together and get different perspectives from one another. When you have multiple perspectives, you’re gaining more awareness of a situation … We need to be offering diversity as learners.”

Although Grant does have an extensive special education program with three Intensive Skills classes for both medically fragile students and those with cognitive disabilities, there is still a lack of overlap between special education and general education. Most students are secluded to the special education classrooms hidden in the corner ends of the school.

While Kowitch’s experience in general education classes has been mostly positive, it hasn’t always been easy.

Locating a teacher who will accommodate to her needs, keeping up with the curriculum and finding a place in a sea of students who learn differently than her have all taken a toll on Kowitch.

But despite the struggles, Kowitch and her parents say that inclusion is a vital aspect of special needs education.

“Grace’s social and learning skills have been enhanced by the higher demands placed on her from being with typical students,” says Kowitch’s father, Art Kowitch. “The (general education) students also gain improved empathy and appreciation for difference, from exposure to students with different learning styles and capabilities.”

For Grace Kowitch, being involved in the school community isn’t about proving something – she just wants to be seen as another student. “I love school, and it is so nice to be in general education because everyone treats me the same as everyone else,” says Kowitch.

. . .

Kowitch was born two weeks early on September 21, 1998, to parents Art Kowitch and Kris Anderson and her older brother, Sam Kowitch. Minutes after she was born, the doctor told her parents that Kowitch had Down syndrome, leaving them scared for her future.

“We had a lot of worries … socially how the world would treat her and would be like for her,” says Kris Anderson. “It was all new and different and was certainly something we never anticipated.”

On top of this, her parents soon learned that Kowitch was born with a hole in her heart. At such a young age, surgery was a risky option. But they decided to go through with it, and after eight days, she was fully recovered. It earned Kowitch the nickname “scrapper”– a family saying for someone who is always up for a fight.

When Kowitch was 3 years old, her parents began exploring options for early education. They wanted Kowitch to practice her social skills from a young age. The family enrolled her at Early Intervention, a system of services that provided Kowitch with the initial help she needed through occupational and vocational therapy. The program, which doubles as a preschool, also helps individuals with physical and mental illnesses practice daily activities

After full days at the preschool, Kowitch would come home exhausted. “She was like a sponge,” says Kris Anderson. “She soaked up all the new material, and when she was on the bus, she fell asleep because she was so tired.”

In 2004, Kowitch began kindergarten at Laurelhurst Elementary School in Northeast Portland. At the time, the movement to further incorporate those with disabilities into the general student body was in its beginning stages, and for the most part, inclusion in the classroom at her school and across the district was few and far between.

Historically, all students with disabilities were isolated from their peers in separate buildings and didn’t interact with general education students at all. In the 1950s and 60s, special-needs people were housed in state institutions, often times with minimal food, clothing and shelter. Physical and emotional abuse was also rampant throughout the sanctioned facilities and needless to say, there was no form of education for the residents.

“A lot of the students I work with now, 30 years ago, they would have been in an institution, which is really scary to think about,” says Megan Hull, a special education teacher at Grant.

By 1968, the federal government had supported training for just 30,000 special education teachers and related specialists. But educational opportunities were still lacking for the majority of students with special needs. In 1970, U.S. schools educated only one in five children with disabilities, and many states had laws excluding certain students from school.

Since The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act was enacted by Congress in 1975, that number has slowly started to rise.

Still, even just ten years ago, many teachers and parents were outwardly opposed to the idea of inclusion, and some still are today. Kowitch’s parents remember how others complained that special education students would negatively impact their children’s education, and teachers were frustrated that the district would put special education kids in their class without any support. “Certainly there were a lot of people who were not supportive of that, but we really were,” says Art Kowitch.

Cody Sullivan, who has Down syndrome, graduated from Grant in 2014. As a high school student, he took general education classes and helped out with the football program. His mother remembers facing similar struggles around inclusion in general education classes starting when her son was in kindergarten. “We have had to fight for it,” says his mother, Anne Sullivan.

Kowitch also faced some hurdles when she began exploring different interests. In 2004, she wanted to take Taekwondo after watching her brother at practice. The instructor told Kris Anderson that he didn’t know if she “could do” Taekwondo. Kowitch didn’t agree with him.

“I don’t remember exactly what he said, but I felt bad for myself because I thought I can’t do it,” says Kowitch as she pumps her hand into the air. “I proved it wrong, so I kick butt.”

Her older brother, Sam Kowitch, says that people don’t mean harm when they speculate about her capability to do something. “I think they just have a general misunderstanding about Down syndrome,” says Sam Kowitch. “Grace is capable of anything.”

Kowitch came back the next week to take the class, and it wasn’t long before the instructor changed his mind. She earned herself a blue belt in the 3rd grade, and the instructor even gave her the “Student of the Month Award.” “Grace decides she wants to do something, and she goes for it,” Kris Anderson says.

By middle school, Kowitch had taken her position in general education classes to the next level. She was learning Spanish with her peers, participating in the science fair and keeping up with her school work. She had become somewhat of an inspiration for the other students in her class, and so for graduation, she was asked to give a speech for her peers.

After prepping for the speech for days, the written copy was lost the day of her 8th grade promotion. But that didn’t phase her. Kowitch decided to just wing it. “It was an epic speech,” says Art Kowitch. “She was not the nervous one, we were.”

“I nailed it … bam, what?” says Kowitch, using her favorite catchphrase from the Disney T.V. show, “Liv and Maddie.”

During her freshman year at Grant, Kowitch continued on the same trend and took all eight general education classes – which is rare for students with disabilities – with the help of an aide.

But for her parents, it wasn’t a surprise. It was what they expected.

“Grace has always been a strong advocate for herself,” says Art Kowitch. “And with the supports in place, it enabled us to feel comfortable, reassured and reasonably optimistic about Grace’s transition to Grant.”

That same year, Kowitch joined “Team Together,” a club that helps bridge the gap between students with disabilities and those without through activities during lunch.

During one meeting when there was a discussion about kids with and without disabilities, Kowitch became exasperated. “I remember she was like, ‘What’s the difference between people with disabilities and people without disabilities?’” says Kris Anderson.

Kowitch started to realize that she should be helping out others in the same place as her. So, with the help of her private speech therapist, Kowitch was paired up with a student at Jackson Middle School, Iris Tervo, who also has Down syndrome. Kowitch started mentoring her, mainly focusing on building vocabulary, making eye contact and continuing a conversation.

Kowitch brings a vocabulary book that she received in 7th grade to the mentoring sessions and uses it to help Tervo practice her S’s and L’s.

They also take their mentoring sessions out into the community, going to Whole Foods to practice talking and making eye contact with the cashier as well as drinking, chewing and swallowing food.

When her mentee goes into “shutdown mode” where she puts her head down, Kowitch tries to cheer her up.

“Iris is a bowl of fun. Sometimes I tickle her, and sometimes I draw a picture for her,” says Kowitch. “I help Iris with her speech, and she helps me speak slowly too.”

While Kowitch acts as a mentor for someone with Down syndrome, she herself realizes that she still has hurdles to overcome in her own learning process. After freshman year, Kowitch and her parents faced the reality that Kowitch can’t just take any classes she wants. The teacher needs to be willing to adapt their curriculum, and their interactions with Kowitch must be hyperfocused. General class requirements sometimes have to be changed, which makes finding the right class for Kowitch increasingly difficult.

Throughout her four years, Kowitch’s involvement in special education programs ebbed and flowed. After freshman year, she began taking some special education classes to balance the increased workload of higher level classes.

Dan Anderson, a social studies teacher at Grant, is a firm believer that teachers need to find ways to make their curriculum work for students with special needs. Over the past couple years, he has watched Kowitch learn and grow in his classroom. He says she has been a star pupil.

“She is the most organized student I know. If I could translate her work skills and her level of responsibility to the general student population, every kid in the building would be a 3.8 GPA or above,” he says. “She is sassy with a good sense of humor, and she is super kind and sweet.”

Her senior year, finding classes became even more difficult. Only certain subjects with specific teachers are available to teach Kowitch. Because of this, her curriculum has become more and more narrowed and her class workload is more difficult. Many teachers and administrators still struggle to find ways to make all curriculum work for special-needs students. Kowitch and her family have had to make due with what is available.

“It became more about not the class, but finding the teacher,” says Art Kowitch.

Hull recognizes that there is still much work to be done within the inclusion movement. “We still have a really long way to go, and this is a conversation that special education teachers are trying to have with elective teachers is, how do we have our classrooms be more inclusive, and what does that mean?”

Others worry that as a whole, the special education program is lacking resources. “Special education is a federal mandate but is not funded,” says Mary Pearson, the director of the Special Education Department for PPS. “We are constantly moving things around to accommodate the highest needs.”

This is partly why finding classes for Kowitch and others can be so difficult. Without funding, classes are cut and moved around frequently to make ends meet. “In the special education department, things never stay the same,” says Kris Anderson. “Everything is constantly in flux, which is frustrating.”

But through it all, Kowitch has still found her own ways to excel by putting herself out in the community. And now, as senior year is coming to a close, Kowitch isn’t slowing down.

Between working at Wee Works Preschool for 1.5 hours per week, rehearsing for “Chicago” – the new school play she auditioned for and claimed a role as an inmate – and basketball practice, Kowitch is always busy. This year, Kowitch was also awarded the “best dressed” senior superlative for Grant’s yearbook.

“It feels good,” says Kowitch. “Because, you know, I am a fashionista.”

Now, Kowitch is preparing to start her next journey and she is setting her sights higher than ever. She is waiting to hear back from the “Think College” program for students with cognitive disabilities at Portland State University. “I am ready to leave Grant High School and go to college … and travel the world, get an internship,” she says. “I am going to do all the things that every other person is going to do.”

By Kowitch attending college, Grant would be continuing a new trend of ensuring students with Down syndrome have equal access to higher education. Cody Sullivan, the alumnus from 2014, is now a junior at Concordia College and is the first student with Down syndrome in Oregon to attend college. While the leap to college is a big one, Kowitch’s family and friends are confident that she can overcome anything that comes in her way.

“We were very lucky to be surrounded by people who see her strengths, which helps us see her strengths, which helps her to highlight her own strengths,” Kris Anderson says, “She just never quits impressing us.”

Kowitch puts it simply. “That’s how I roll,” she says. ◆