Portland has the second highest percentage per capita of LGBTQ+ residents out of all the metropolitan regions in the United States. Walk down its streets and you’ll see rainbow flags and equal marriage bumper stickers galore.

It’s widely considered one of the most progressive and accepting cities in the country, and Grant High School is thought of as a pioneer of sorts when it comes to these issues. But look closely at our community and the experiences of our LGBTQ+ students, and you’ll see that we have a long way to go before we can truly deem ourselves fit for such ambitious labels.

While it may be common to see a Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network “Safe Space” sticker or poster in a classroom, it’s uncommon for teachers or staff to ask students or colleagues what their preferred pronouns are. This may come from a lack of knowledge around the fact that many people identify with a different gender than the sex they were assigned at birth, and others do not identify within the gender binary of male or female at all.

When a faculty member fails to ask for preferred pronouns, or addresses their class as “ladies and gentlemen” or “boys and girls,” they are failing to recognize the existence of their transgender and non-binary – those who don’t identify as a specific gender – peers. Furthermore, they are perpetuating a culture that has too long dismissed the basic rights of LGBTQ+ people.

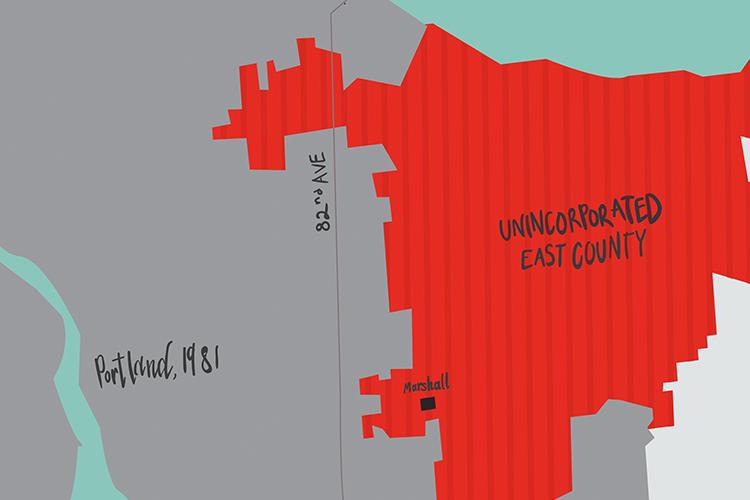

A big step for Grant happened in 2013 when administrators implemented gender-neutral bathrooms. At the time, a nationwide conversation around bathrooms for transgender and non-binary people had been percolating. Cases roiling with conflict about the use of bathrooms by transgender youth dotted the country.

A 2013 study by the Williams Institute in D.C. at the time found that 70 percent of transgender or non-binary people reported being denied access to a bathroom or being verbally and physically harassed after entering one.

The gender-neutral bathrooms at Grant gave students and staff the opportunity to avoid the uncomfortable and potentially dangerous situations of choosing the bathroom assigned to the sex they were given at birth, choosing the bathroom assigned to the gender they identify with (which, in the case of non-binary people, didn’t exist) or not going to the bathroom at all.

While the installation of gender-neutral bathrooms may have helped to alleviate a big issue at the school, most students now don’t even know about the bathrooms. And to this day, we only have male and female locker rooms. One year of a physical education class is required for all students going through Grant. So how many students who don’t identify with either gender are left feeling uncomfortable and isolated because there isn’t an option for them?

Oftentimes, straight and cisgender people – those who identify with the sex they were assigned at birth – disregard these issues because they don’t have to think about them.

This creates the idea that aggressions toward the LGBTQ+ community do not exist, especially not in Portland. But that’s wrong. Students we interviewed say they can’t go a week without hearing the phrase, “That’s so gay,” or being called slurs like “lesbo,” “fag” or “dyke.”

It’s disturbing that some students at Grant have taken to treating the concepts of triggers and safe spaces as jokes. But the reality is that LGBTQ+ students frequently feel unsafe in school, and safe spaces are a way to help ease that. And trauma triggers are a real psychological reaction proven through multiple studies.

Attention to detail is key for these issues because other disparaging traditions that exist in our culture of education take a huge toll on students. In the same way that students of color bemoan the lack of representation in curricula, the same can be said about the LGBTQ+ community.

Our health classes are designed by and for straight people who identify as their given gender, rendering them nearly useless for our LGBTQ+ students. Our history classes ignore the past of LGBTQ+ people, leading many to believe that being LGBTQ+ is something new or some type of phenomenon.

Our biology classes fail to explain the difference between sex and gender. Our English classes continue to choose narratives that predominantly tell a single story: one of straight, cisgendered whites.

The most important thing Grant can do to make our school a better place for our LGBTQ+ students and staff is create a platform for their voices and ideas. People must be willing to have open ears, open eyes and open minds.

In a society that often fails to tell the stories of LGBTQ+ people, it’s not rare that people struggle to grasp these topics.

It’s time to start recognizing the impact of our current habits as a school and as individuals. We mustn’t accept the labels of “accepting” and “progressive” and call everything good. We have come a long way, but we still have a long way to go. ◆