Ahmad Hill takes a breath before bowing to his opponent. A wall of mirrors gives the impression that the dimly lit dojo is much more immense than the small room truly is.

Padded green floors sink under the weight of the fighters. A timer goes off, and a powerful kick lands on Hill’s stomach. He grimaces but retaliates with a well-thrown right jab that lands in the center chest of his adversary. The two go punch for punch until a timer rings and they bow again.

Hill, a senior at Grant High School, has made martial arts a way of life, spending much of the last decade practicing. But when his father’s U.S. Army infantry unit was deployed to the Middle East, the activity grew into a way for Hill to cope with the constant fear he had about losing his dad.

“With my dad being deployed, it was like everyday, any day, at any time he could just die. And that’s scary, you know?” says Hill.

His dad made it back unscathed after tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, and from that, Hill chose to immerse himself further into karate and its cultural history. Martial arts had been Hill’s escape from reality. Now, when he steps inside his dojo, he enters his sanctuary.

“Doing martial arts just centered me,” Hill says. It “gave me something to work towards and keep a calm mind.”

Born July 16, 1998, in Atlanta, Georgia, Hill is the middle child of three. Early in his life, both Hill’s parents worked, so he and his sisters would spend their time in the backyard of their daycare, playing tag and hide-and-seek.

In elementary school, Hill’s teachers often had to call home because he was too rambunctious in school. Hill describes himself as a class clown, and he often paid the price for his antics, mostly being off-task and distracting other students.

Larry Hill, Ahmad Hill’s father, remembers countless parent-teacher conferences when he learned about how his son continued to disrupt class. “When he was younger, he wasn’t (disciplined),” says Larry Hill.

Ahmad Hill remembers his father’s looks of disappointment, but it wasn’t enough to change his behavior.

It was in kindergarten when he first thought about martial arts. One day while watching TV, he stumbled upon “Enter the Dragon,” a popular martial arts movie from 1973 starring Bruce Lee.

Lee’s unique skills and incredible ability as a fighter inspired Hill to want to be just like him. “Just his power. Who couldn’t be drawn into that?” Hill says now.

That memory never left him. Four years later, at age 8, he started taking mixed martial arts classes once a week. But he was drawn to taekwondo. “I started doing it, and it was just something in me. It was a connection,” he recalls.

Just as Hill began to thrive in his taekwondo classes, his father was deployed overseas.

In 2009, Larry Hill was sent to Iraq for six months. Ahmad, who was 11 at the time, remembers the hole that his father’s departure left in their home.

He had always counted on his father, but for that six months, he wondered if he would ever see him again. “Is he going to die?” Hill often asked himself. “Will people come to my house, knock on my door and say my father is dead? That’s what was on my mind, everyday.”

While his father was away, Hill stuck with martial arts, but his motivation was still lacking. He continued to struggle and get in trouble in school.

When Larry Hill returned, the family was stationed in Louisiana but later moved to Washington state, looking for a better school system for the children. Hill’s slacking tendencies in school didn’t improve. “Before, he used to play video games. I would try to tell him to go out and play a sport or something, give it a try,” says Tamara Hill, Ahmad’s mother. “He wasn’t really motivated.”

After school, Hill would come home and plant himself in front of the television. But after entering sixth grade, he started to get serious about martial arts, going to more and more classes each week and practicing his moves at home. This, he says, improved all aspects of his life: his physicality, mental well-being and grades. “It was a realization that I had to do what I had to do to better myself and grow up,” says Hill.

His father saw him make a change. “It was a big change. The older he got and the more classes and training he got, his academics went up, skyrocketed,” says Larry Hill. “That’s him maturing in age and personality, and the way he handles himself now.”

In 2012, Larry Hill left again for a military tour in Afghanistan for a year. His father’s departure hit Ahmad Hill hard, but martial arts was there as his crutch this time. “Doing martial arts centered me and gave me something to work towards and keep a calm mind,” says Hill.

Hill and his family were able to video chat with his father a couple times a month, but the conversations were often brief. For the Hill family however, it was key in shortening the distance between themselves and Larry Hill. For Ahmad Hill, the video chats let him know that his father was still alive.

While he couldn’t control what was happening to his father, the precise movements and repetition of martial arts gave Hill control over his own life. After school, he would head directly to class. “It was a therapy for me. It took my mind off things. Just like leave it outside and focus on yourself,” says Hill. “When my father went overseas to fight … it helped me. It was always there.”

When Larry Hill arrived home from Afghanistan in 2013, Hill and his family waited from morning until evening in a small military base gymnasium to greet him. When his father walked in, Ahmad’s mother cried. But to Hill the interaction was odd. A rush of pure relief ran through him. He explains the feeling as surreal. “I can’t explain it. I can’t even put it into words; a person who it (hasn’t) happened to wouldn’t understand,” says Hill.

With his father back, the Hills were once again stationed in the South, this time in Fort Benning, Georgia. The lack of dojos in the area made taking taekwondo classes nearly impossible. But when he had time, Hill practiced the moves and techniques he had learned earlier.

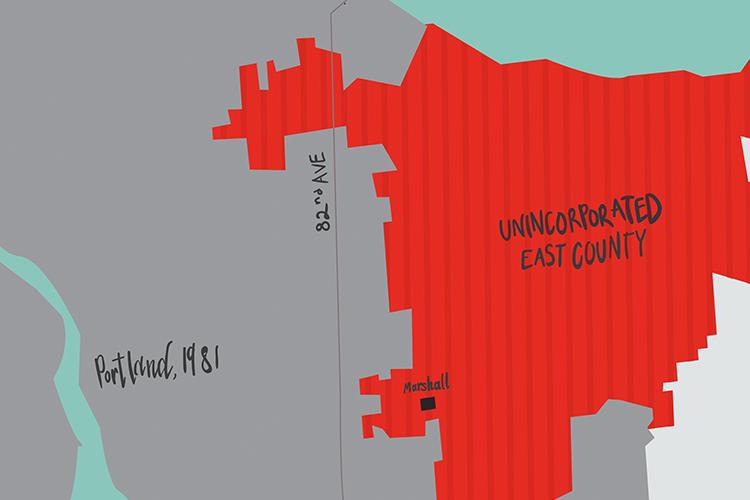

Once again, the Hills packed up and moved, this time back to the Pacific Northwest. Hill was 16 when they settled in Portland. He started judo lessons before switching to karate.

Hill was so drawn to the Japanese martial arts that he became determined to learn the language. He taught himself some words and picked up the basics of the language, and as he did so, he discovered an interest in Japanese culture as well.

When Hill first came to Grant as a sophomore, his only goal was to enhance his Japanese skills. But first-year Japanese wasn’t offered at the time. So Hill went to the Japanese classroom in his free time to learn as much as he could. “It was just learning the alphabet and learning a couple words, but it wasn’t like I could understand it. That’s why I kept coming back, trying to better my Japanese skill,” says Hill.

In the last year, Hill began attending karate classes at Kyokushin Dojo in Beaverton. He sacrifices nearly six hours of his free time after school almost everyday to bus to his class and stay for two sessions of practice.

“To learn this you need to be really patient, so you learn about patience,” says Hill’s karate teacher, Yoshi Ito. “Also, if you get hit, it is painful. So we have to learn what pain is. If you hit other people, other people feel pain. So it means caring about other people.”

Hill competed in a local tournament earlier this year. The experience was eye opening and exposed him to another side of the sport he loved. “When I go to a tournament, I … test my own skill,” he says. “I’m doing it for myself.”

Today, Hill continues to study the Japanese language. He only has been in the class for two years, but his learning far exceeds the time spent in class. That’s no surprise to his teacher, Kazuko Page. “He has passion; he has a dream of going to college in Japan. And when you have a tangible like that, the motivation is very strong,” she says.

After graduation, Hill plans to join a six-month, pre–college program in Japan to introduce foreign students to the culture and expose them to new experiences with the language. He hopes to stay and attend college. “That is my next step in life, to go to Japan. And that’s like the golden ticket right there,” Hill says.

But college isn’t the only reason Hill dreams of a life in Japan. He wants to train under a karate master. “I want … to go to Japan and actually have a connection with a master. I want to truly speak to him and not just speak English,” explains Hill.

Training under a master where karate originated is a necessity for Hill. In his eyes, the lessons learned through martial arts can be life changing. When he grows up, he hopes to give the same opportunities that the sport gave him to the next generation.

“Why do I do it? It strengthens me, my mind, my body, and my spirit,” he says. It “gives you a path in life. It is something to always strive for and it won’t disappear.” ◆