Eleven-year-old Marcella Stanard sits on the edge of her seat. It’s her first time seeing the traveling acrobatic show “Cavalia,” and the excitement in her eyes is apparent.

The stage lights up as the horses and acrobats appear before her. Their stunts blur together as Stanard stares in amazement.

Her mind jumps to the future as she pictures herself moving and twisting her body on the backs of the same galloping horses. Little did she know she would soon be making steps toward this reality.

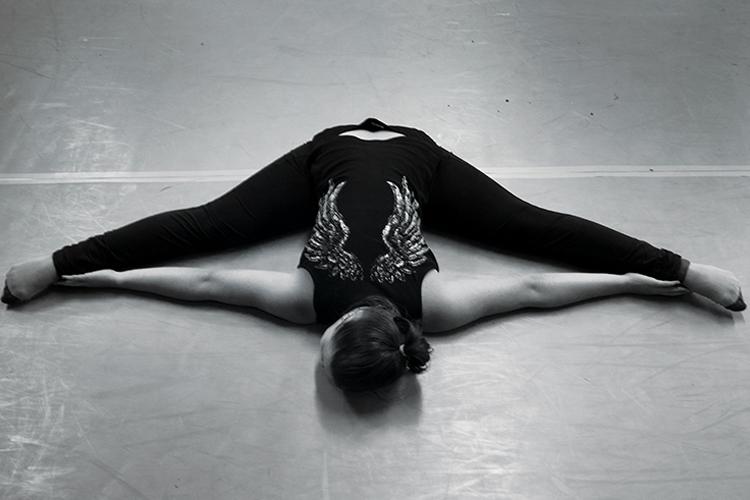

For two years, Grant sophomore Stanard has been practicing contortion, an act of twisting one’s body into unusual positions. “I think it’s really helped to have something that … no one else has,” Stanard says. “I like the artistic-ness of it … and I like pushing myself.”

Her older sister, Mika Stanard, has seen how contortion has shaped her sister. “She practices at home all the time,” says the 18-year-old Mika. “You’ll always see her just doing handstands against the door or randomly stretching her side-splits on the wall. She’s always doing something.”

Marcella Stanard began practicing contortion in eighth grade and has been hooked ever since.

Maisie Topping, a close friend, has known Stanard since they were in third grade. “It’s really cool to see her doing contortion because that’s crazy,” Topping says. “She’ll just casually be talking to you, and she’ll start stretching, and she’s like folding herself in half, and it’s just the weirdest thing.”

Before that, Stanard says she always tried to follow in her sister’s footsteps, especially when it came to academics. “I didn’t really bother to realize that we wanted different things,” Stanard says now.

She has used contortion as a way to take her life and make it her own. “She’s always been like the golden child,” she says about Mika Stanard. “It’s really nice to find your own thing that you like and are good at.”

As a child, Stanard was known for her energetic behavior. Her parents remember her constantly running around outside or jumping off the arm of the couch.

Stanard recalls a close-knit relationship with her sister. Mika Stanard has Asperger syndrome, and the girls’ parents split about eight years ago, which made the girls inseparable.

But given Mika’s academic talent and love for all things scientific, Stanard felt pressure to be like her. Taking after her sister, Stanard tried out for her middle school Science Bowl, a highly academic competition, even though she held little interest in the subject. She didn’t make the cut.

“I think I was a little bit sad that I had never made it, but at the same time I was sort of relieved because … I don’t think I ever really cared a ton,” Stanard says. “So I didn’t have to keep doing something that I wasn’t really that into and wasn’t really that good at.”

“That was like the first time that I started thinking, ‘Maybe she’s not the same as Mika. Maybe this is not where her true passion is,’” says her mother, Jill Sanders. “It took a while for Marcella to like really think that she could have another path, that she could do something different.”

Stanard yearned for a hobby of her own.

Having always been unusually flexible, she started an aerial class at Echo Theater with Do Jump, a dance and acrobatics company, in the beginning of eighth grade. On the first day, her nervousness was quickly replaced with a newly found confidence. As she looked around the room, her natural talent stood out among the rest.

“We, every week, would like warm up with … the splits, and everyone else was like one to two feet off the ground, and I was like a couple of inches off the ground. And I was like, ‘Wait a minute, I’m really good at this,’” Stanard recalls.

She continued taking classes every Saturday for the rest of the school year. It marked a new beginning. “I just started doing it every time that I was like watching TV, and then I got better at it, and then it kind of like evolved into an obsession,” she says.

Now every Tuesday night, Stanard spends two hours at her aerial class. They start with conditioning and warm-ups and then move on to the silks and trapeze, working to perfect the skill set planned for the day. Though every class leaves her sore, she says, “It’s only two hours, but honestly, I’d do it all the time if I could.”

In any free time she can spare, her bedroom becomes her studio. She practices twisting, bending and stretching against walls, chairs and a pillar in the middle of her room. It serves as part of her everyday routine. “I stretch like an hour or two every day, not because I dedicate time. Just because I do it casually,” Stanard says.

Her commitment hasn’t gone unnoticed. “I’m so proud of her for finding something and practicing it … and getting better and better at it,” says Marcia Stanard, her other mom. “I think that’s really cool. And I love it, and I love the effort and dedication she puts into it.”

For Stanard, contortion goes beyond being a hobby. It’s provided her a means of coping with her anxiety. “It calms me down so much. I’m constantly just like, hyper and jittery, and I don’t want to be,” she says.

Now, as she looks to the future, Stanard knows her love for contortion will follow her into the coming years. She plans to attend École Nationale de Cirque, a circus college in Montreal, Canada.

“As Marcella’s kind of like coming into her own, I just really want to support (her) and encourage (her),” says Jill Sanders. “Because you know, you don’t need to make $60,000 a year when you graduate from college … You can do something else. You could travel the world or travel with the circus.”

For Stanard, being able to find her own passion has proven to be a breakthrough. “What I’m doing now, I honestly just … really like doing all the time,” she says. “That’s important, that you like the process instead of just the idea of it.” ◆