Branic Howard remembers the final performance for his degree in music composition at Portland State University.

It was 2009, and he stood in front of an audience of 50 people in a downtown Portland church. In one hand he clutched a potato, the other: a sharp knife.

Inside the potato, Howard had meticulously placed small hidden microphones. He angled the knife, rhythmically cutting into the potato’s skin. The effect? An electrical sound that filled the church and mesmerized the audience.

His performance of “Potatoes Hold the News Down At the Bodega,” named in honor of a poem by Tom Blood, solidified Howard’s non-traditional look at what music can be.

“It was a turning point…I think it was a turning point for my mom. She realized I wasn’t as normal as she had hoped,” he says, jokingly.

Howard’s relationship with sound has proven to be anything but ordinary and is something that’s been clear to him since childhood. For as long as he can remember, he has gravitated toward listening and interpreting daily noises most people fail to recognize.

It’s unconventional, to say the least, as Howard lists several irritating sounds, like the buzzing from an air conditioning unit. “People say, ‘That’s noisy,’” he points out. “When I hear something like that, I don’t think of it in the same way. I say, ‘I like that noise. I like that sound. I find it pleasing, and I find it interesting.’”

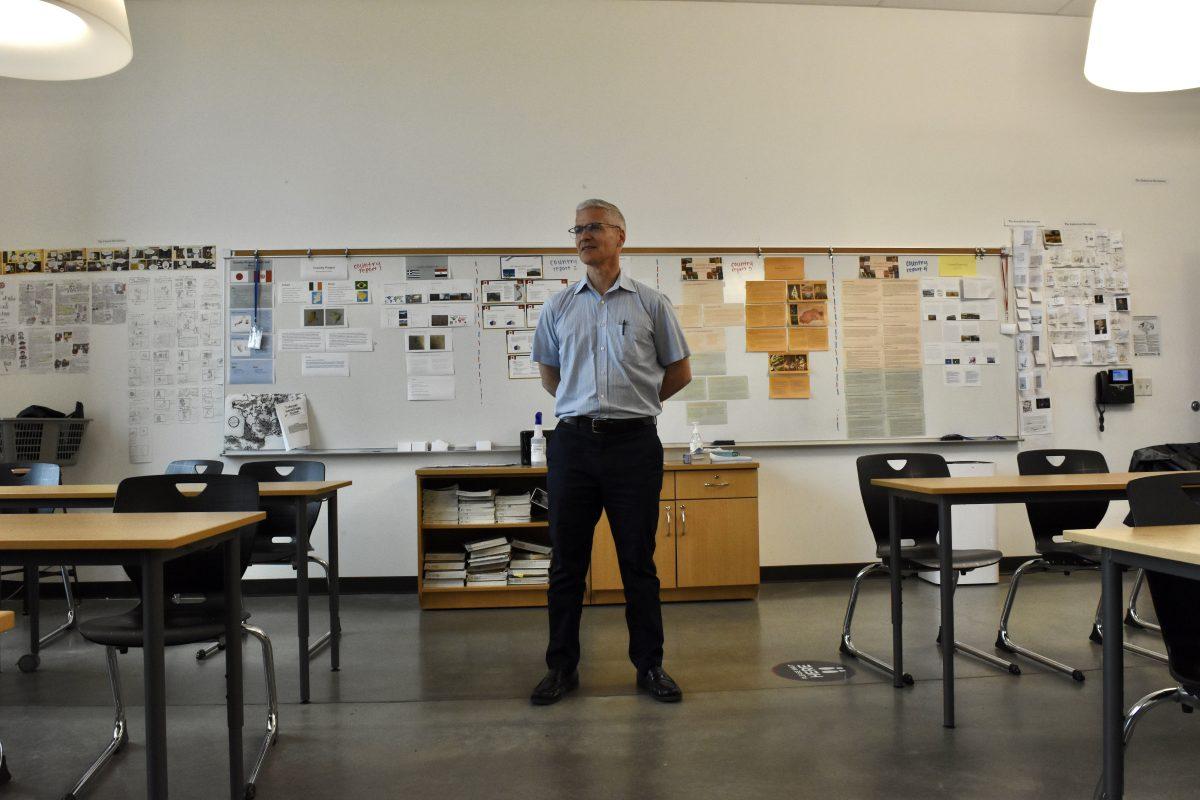

He’s working toward his doctorate in music composition from the State University of New York at Stony Brook while teaching audio engineering and guitar at Grant.

Howard’s mission is clear. He hopes to share his passion for sound with students in a musically hands-on environment. Getting students actively involved in creating music of their own has been key.

“A lot of people would be like, ‘Oh that’s just noise’ but I see it as something that has inherent beauty” – Branic Howard

“It’s so cool to see people change … their lives,” Howard says about teaching. “They did something and now they have that experience, and I got to play a small part in facilitating that experience for them.”

Howard was born on Oct. 14, 1983. He was an adamant listener as a child, forging an immediate connection to sound.

He remembers taking a handful of Lincoln Logs, piling them into one of his dad’s socks and rolling it around to hear the wood-on-wood sound effect. “I would do stuff like that and just put it up close to my ear and listen, and that was my lens into the world,” he says.

Howard and his sister, Britt, grew up in a close-knit family in Vancouver, Wash., going over to their grandma’s house every Thursday night for a big dinner with relatives.

But by the time he was 4, his parents divorced, causing Howard to grow apart from his father.

His mother, Kellie Cooper, remembers Howard as an introverted child, constantly channeling his relationship to noise: “I would find him like, ‘Where’s Branic? Where’d he go?’ And then I’d find him sitting behind a door with his toys making sound effects and making helicopter noises.”

Howard remembers having synesthesia-like symptoms, where he would associate certain sounds with colors. “I very clearly remember sitting in my mom’s little Austin-Healey… listening to The Beach Boys and seeing the color turquoise, feeling the color turquoise,” he recalls.

As for music itself, Howard’s exposure was limited. In his house, he remembers having just two vinyl albums: one by Bruce Springsteen and another that was a Halloween music soundtrack.

At Evergreen High School, Howard was a dedicated cross country runner and maintained straight A’s.

Despite his atypical interest in sound, he says the music department at Evergreen was lacking. “I was obsessed with sound, and I think I always knew that, but I had no outlet,” he recalls. “In high school, no one said, ‘Why don’t you try music?’ I just didn’t have that.”

His interest in music wasn’t solidified until his pottery teacher helped him discover a new outlet. Howard remembers skipping class just to go down to the pottery room. The teacher burned him a variety of CDs of artists he had never heard of, like a Cuban group, Buena Vista Social Club.

“That was my early influence into how good music could be… people who have poured their whole lives and generations before that, people who have passed down a tradition of music that’s just so humanistic,” he says. “It really spoke to me.”

He graduated from Evergreen in 2002 and moved to Portland. He attended Portland Community College, thinking he wanted to become an engineer. Between classwork, Howard remembers always being in the library where he’d research new music online. He later transferred to Portland State University.

At PSU, he found a place he felt he belonged. “There were other people around me that were like-minded, not just other students, but the professors,” he recalls. “I felt like I was in a community that made sense to me.”

In 2006, Howard co-ran Portland New Music Society, an organization that scheduled musicians from across the country to come play in Portland. Then, in 2009, Howard received his bachelor’s in music in composition.

After graduating, Howard made the bold decision to move to New York City and attend Syracuse University. He moved into a predominantly black section of Brooklyn with his now-wife, Gabriella Lewton-Leopold.

Howard says it contrasted so dramatically with his experience in Portland that he considers it to be “the most important experience” of his life, one that had a heavy impact on his perspective.

In Brooklyn, Howard was exposed to an array of music, constantly going to old jazz clubs at night. Meanwhile, his own composition underwent change as well, as he explored unique sounds in what he calls “noise music.”

He would sit for hours along the coast of Maine, recording equipment in hand to catch the sound of the waves hitting the rocks. “A lot of people would be like, ‘Oh that’s just noise,’” says Howard. “But I see it as something that has inherent beauty.”

As a means of income, Howard started his own business called Open Field Recording. He graduated from Syracuse University with a Masters in music composition in 2011. Three years later, he and his wife moved back to Portland.

He continued working for his company, recording for local groups like Third Angle New Music Ensemble. On the side, he composed his own music, using non-traditional sounds. When a teaching position in audio engineering and guitar opened up at Grant last August, Howard jumped at the opportunity.

Remembering the impact his pottery teacher had on his musical career, Howard wanted to replicate that experience. “I thought: OK, I have the opportunity to maybe do that for one student every five years,” he remembers thinking. “Of course I want to be a high school teacher, and I got hooked right away.”

In his audio engineering course, Howard helps students develop their own music and learn the intricacies of composition. The class has proven to be unique among the course offerings at Grant.

Junior Taylor Crotteau, who enrolled in both of Howard’s courses last year, says the class opened her up to a new career field. Howard’s audio engineering was more than an average class, she says. “Before, I hadn’t really tuned in to smaller sounds that were around me… how sound impacts everything that we do, everything that we take in,” she says. “My perspective definitely changed.”

Howard says being able to create that uniquely sonic learning experience for students has been key. His devotion to educating others is made clear in the classroom every day.

“It was really inspiring how much he cared about what he did and every student’s projects, how he would nitpick at every detail to help you,” says junior Nikole Roy-Johnson, who took audio engineering last year.

As Howard keeps busy with teaching at Grant, he still records music for artists on the side with Open Field Recording. “It’s absolutely a passion,” he says, chuckling. “I’m laughing because it’s almost like I have a problem. It’s all I think about.”

As he teaches, Howard is working toward a doctorate, which will make him a rarity among Grant staff.

Art teacher Lynn Yarne says her colleague’s vast knowledge of music doesn’t go unnoticed. “He’s very intelligent without being overpowering or arrogant,” she says.

“It’s really apparent how much he respects his students as artists, not just as students.” – Lynn Yarne

With the little free time Howard has, he can be found composing his own music. Given Portland’s natural setting, Howard likes to record in remote rural areas, carrying his hefty microphones and wind guard with him.

Howard stores the new sounds, along with hours worth of past recordings, readily available to combine and edit into music.

As he moves into his second year of teaching at Grant, he wants to open up the student body to a unique perspective in music.

“I definitely try to use my own experience as a way to kind of provide some new ways of thinking,” he says. “That’s the thing as an educator that I’m always thinking about. How can I open up a window for somebody that otherwise they wouldn’t have?” ◊