The question made me cringe.

A student in my government class asked: “Are Native Americans allowed to vote?” My teacher was unsure how to answer, and I couldn’t believe what I had just heard.

I raised my hand and felt all the eyes in the room turn toward me. My dad – a proud member of the Navajo Nation – votes, and I’m planning on voting; we follow the same laws as everyone else. If we’re not citizens of the United States, what are we? Some “other” group?

The answer was obvious to me. But I held back my distaste of the situation and just said, “Yes.”

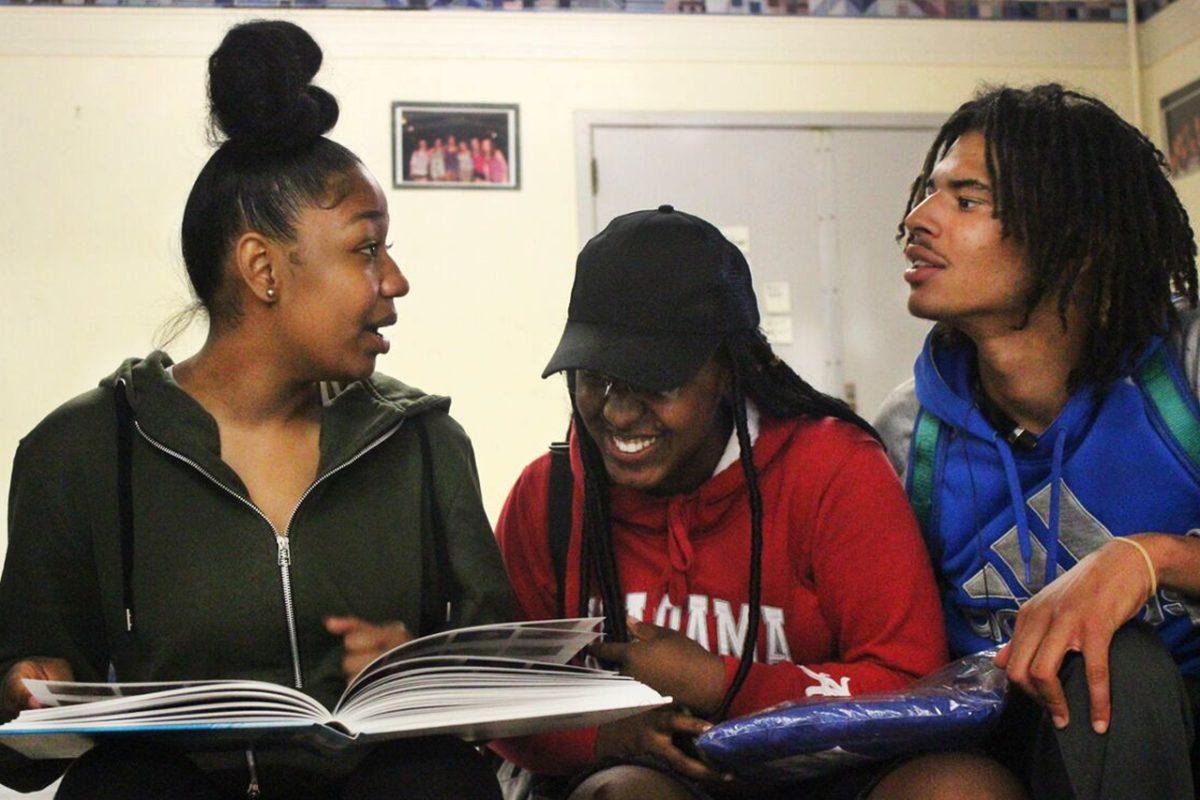

This exchange followed me through the rest of the day. I feel similar to my peers in many ways, but this instance made it clear that I am different. I was the only person in the class of nearly 30 people that seemed to know the answer.

In the past, I haven’t let myself get angry by things like this.

From the outside, I don’t think I stand out as Native American. I don’t feel I am judged like someone with darker skin might be. I can’t name any tangible moments of discrimination, so when I do get frustrated, I brush it off. I tell myself it’s not my place.

But as I’m leaving Grant, I recognize that I have to speak up. Few of my peers share my family’s history. Few have relatives who were forced onto reservations where their names and experiences were pushed to the edge by European and American ambition. Few walk through the school with the same feeling as I do.

At Grant and in most schools, education around Native culture is an afterthought. In the last four years, I have read one novel by a Native author in class and only one unit in one year of history focused on Native Americans. And this reflects the collective ignorance and apathy that I have seen at this school when it comes to Native Americans.

It hurts me when I hear students complain about my dad, who is a math teacher at Grant, for being too quiet when I know that they couldn’t possibly understand how Navajo culture respects listening, encouraging fewer words and more action, while American culture praises loud voices and in-your-face opinions.

And it infuriates me when teachers tell me that incorporating Native culture into education is a lot easier said than done. It’s not a lofty wish to read a Native author in an English class. There’s no way I’m in the wrong for demanding representation.

Like my dad, I’m Navajo. From a young age, I’ve had an interesting relationship with my culture. I grew up knowing very few people like me but visited the Navajo reservation in Northern Arizona every few years with my family.

I loved playing tag with my cousins in the dry desert afternoons but got nervous when mutton stew was served; I knew I couldn’t chew the grisly parts of the meat. In Portland, my culture was a point of pride. I loved it when people asked: “What are you?” and I could respond: “Navajo.”

I remember my dad telling me stories about his life as a kid. He went to an all-Native boarding school and only came home on weekends. Every Sunday when his mom dropped him off he used to cry because he didn’t want to leave home. Years later, he left Arizona and moved to Portland where he got his master’s in education. He remains rooted to his family on the reservation; they are his cultural base.

My dad’s history adds to how I see and experience things, and it’s offensive to see it ignored in education. I find it ironic that from his perspective the only time colleagues ask him for help is when they want help teaching a lesson on Native culture.

And I don’t see an effort being made to change anything. Next year, “Living in the USA,” an alternative history class that teaches American history through a more diverse lens, and ethnic studies will be combined into one course. But that’s my point.

To me, reserving certain classes for minority perspectives continues to make non-white groups seem “other” and “less than.” Rather than adding classes to complete a diversity checklist, we need to incorporate Native authors and points of view into standard and required classes.

Don’t get me wrong: I walk down Grant’s halls and feel like I belong. But it’s in the moments like my government class where I’m singled out as different. It’s when teachers brush aside criticisms on the lack of diversity in curriculum that my body stiffens. It’s in the whispers of privileged students about my dad where I can’t stand the subtle racism anymore.

I’m leaving Grant, but I have two younger sisters who will continue to be affected by the culture of this school for several more years. I want them to see themselves in their education. I want them to expect more from their teachers and peers. I want them to know that their voices are heard.

But most of all, I don’t want them to be afraid to feel different, because it’s something to be proud of. ◊

Lael Tate is a senior at Grant and will attend Columbia University in the fall. She is also an editor-in-chief of Grant Magazine.