It was a Sunday morning when Pauline Kalamafoni had her faith put to the test.

She sat alongside her family, two aisles from the front of her Mormon church in Lake Oswego. The room was silent, filled with people who hailed from the same Tongan culture as the Grant High School senior. They spoke the same language, and a sense of togetherness flowed from the group.

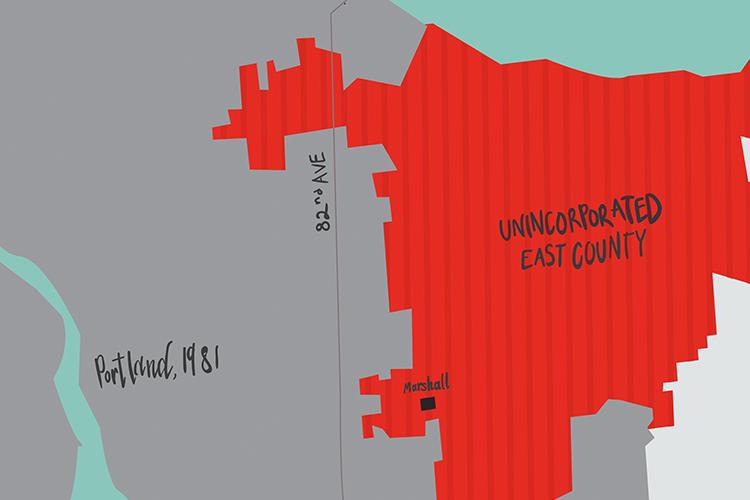

In her mind, though, Kalamafoni had images of hateful messages geared towards herself and the other churchgoers of the Portland temple. The holiest building in the Mormon community was surrounded by protesters, angered by the homophobic values of the religion.

Kalamafoni was awestruck. At her church and in her own belief, gay love and marriage was completely acceptable. Unique in Mormon culture, her congregation accepts gay couples. So that morning, Kalamafoni says she expected to hear a message of hostility to the people that had disrespected her temple.

But the bishop of the church delivered a message of acceptance: “Ai ke lahi ho ‘ofa he ‘oku ikai ke nau ‘ilo ko ha me’a ‘oku nau fai,” he said, Tongan for: “Love them because they don’t know what they’re doing.”

Caught off guard, Kalamafoni was forced to reassess her view, something she’s had to do on occasion when confronting the rules of her religion.

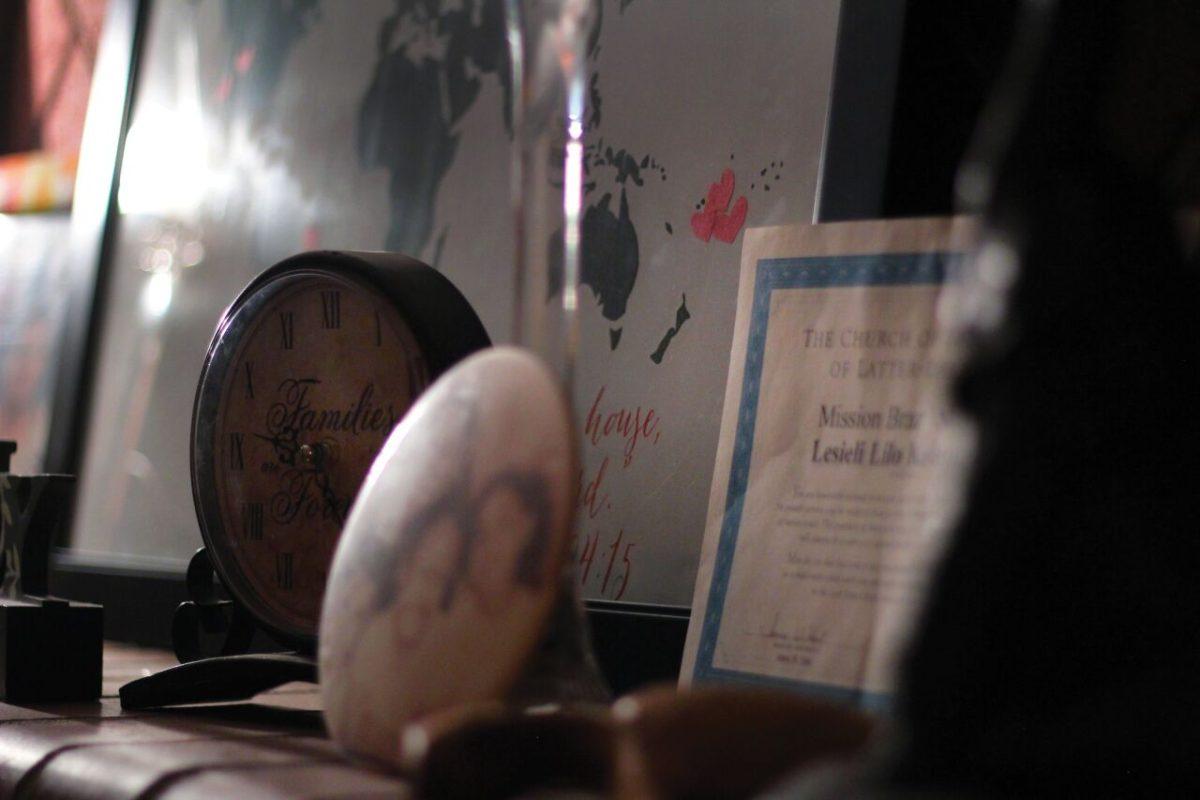

The Mormon church – formally known as the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints – has always been a constant in Kalamafoni’s life. Her Tongan culture also shares similar values to Mormon beliefs. Family first, community solidarity and lending a helping hand are essentials.

“In the Mormon faith, part of the mission is knowing where every person is emotionally, physically, spiritually…and my culture is the same way,” she says. “If you have a cousin’s cousin’s wife that needs help or something, everyone knows about it, and everyone is there willing to help.”

Despite key cultural ties and a welcoming community, until her junior year in high school, Kalamafoni hadn’t fully connected with the religion. The Sunday church service had become a burden for her by the time she reached high school. Mormon practices, she felt, became obsolete. But after her older brother, Wesley, left to the Philippines to perform missionary work in 2014, she had a change of heart.

She recently decided to follow in his footsteps and embark on an 18-month missionary trip starting this summer. The expedition will limit virtually all contact with outside friends and family and requires extensive 12-hour workdays. But for Kalamafoni, the love and security the church has given her is more than enough to convince her to spread the Mormon faith.

“Religion was my main source of security that never changed,” she says. “I mean, family always changes. Your life changes continuously, and so that’s…made it easier for me to be like ‘OK, this is true. I believe in this.’ And because of that, I chose to serve a mission on my own.”

Born Sept. 12, 1997, in Portland, Pauline Kalamafoni grew up the third youngest of six siblings. Her earliest memories date back to long days at their local church as her father, Viliami Kalamfoni, was appointed to bishop when she was only two years old. It was the highest leadership role within the church.

In her family, the Mormon religion and Tongan culture were heavily instilled as both parents grew up in Tongan-Mormon households.

Her parents were adamant about having their children understand where they came from. They chose to speak Tongan in their house more often than English, and Tongan art was plastered around their home. They often visited the Polynesian island when the kids were toddlers, but a trip back when Kalamafoni was 9 had a heavy impact.

While there, the family helped build houses in the small town that her mother grew up in – most didn’t have electricity or indoor plumbing. For her mother, Fasihengalu Kalamafoni, the exposure was vital to their understanding of Tongan life.

“We try to make sure to take them to see how we used to live because we didn’t have much on the island,” says Fasihengalu Kalamafoni. “We tried to show them so they can appreciate what they have over here right now.”

Coming back with a new sense of cultural ownership, Pauline Kalamafoni realized the importance of holding on to her ancestry. “In a way, the culture dies if you don’t carry it on with your kids and your kids’ kids. Eventually, nobody has remembrance of what that was, and then you just become like little dust in the wind,” she says.

In the fall of her seventh grade year, just after her father was released as bishop to their church, her life was turned upside down when her parents divorced. “The first thing I thought was, ‘What are other people going to say about it?’ Because divorce really is frowned upon in the Mormon community,” Kalamafoni said.

She started to feel more alone and she used religion as a crutch. She says: “I dove into church, and people at church kind of helped me so…in a sense, God was helping me because there were so many people available through religion that helped me move past it and be where I am right now.”

But when high school started, friends and parties became a bigger priority, and church fell to the wayside. Kalamafoni remembers often pretending to be sick just to get out of a Sunday service during her freshman and sophomore years. She also started disobeying house rules, staying out 3 hours past her curfew just to get a rise out of her parents. Her distance from the church started to drive a wedge between her and her family.

But a stark change in her older brother’s attitude towards religion forced Kalamafoni to look inwards. She had to make a change.

“It was crazy to see that transformation. My brother went from breaking all these rules, and then he was like, ‘Yeah, I believe in God, and I’m gonna go preach about it.’ I feel like that’s what kind of switched it on for me.”

Now, she says her faith is strong, and her religion goes beyond just praying to God. For her, it’s about community. “It’s always been the community was just like family,” she says. “They’re there to, like, help us and be of assistance or whatever we need, and so I feel like we had that support system with us for so long it’s like, you can’t go back and be like, ‘There’s no use in going to church.’”

Back at home, she also makes community a priority. Her siblings will quickly point to her as the caring and heartfelt one of the family. With three of her older siblings gone, Kalamafoni is often looked to as the caregiver and planner.

In September, she will have to leave for 18 months to an unknown location. As of now, she could find herself in almost any country in the world. The ultimate decision is up to the Prophet – the reigning leader of the Mormon church – and his many counselors for where each missionary will serve their time.

While on her mission, Kalamafoni will only be able to call her family twice a year: once on Christmas and once on Mother’s Day. Aside from that, the program allows for 45 minutes a week to send emails to family. Her day will typically begin at 6:30 a.m. and end at 10:30 p.m., filled with walking door to door and preaching her faith.

For her, the work is inspiring. “There’s always gonna be someone across the world somewhere going through the same thing,” she says. “So if you can help them out by telling them something about religion, why wouldn’t you?”

While the intensity of the mission doesn’t scare her away, she’s still nervous about the uncertainty of the trip. “I take my biggest fears, like getting stuck somewhere,” she says. “I have no idea about the people, no idea about the language. That’s kind of what scares me the most.”

Upon her return, Kalamafoni will attend either Central Washington State or Brigham Young University and plans to major in education with a focus on child development. Her only worry moving ahead is, once again, losing motivation in her faith as the stress of life increases. The biggest deterrent for her is, “really…just the worldly pressures,” she admits. “This sounds really bad, but the laziness of (not) wanting to go to church on Sunday.”

But Kalamafoni is confident that the next 18 months away will give her the passion to stay true to her faith.

“The mission’s really important to me because I’ve spent all this time, 4 years of high school, searching, like, is this true?” she says. “Do I actually believe in this or am I doing this just because of my parents? So now I think that I have a confirmation that I do believe in it for myself. It’s the ultimate test.” ◊