Angelo Accus grips a plastic water bottle in his hand. The 5-foot-6-inch Grant High School senior takes a running start toward a nearby basketball hoop and leaps into the air, effortlessly stuffing the bottle through the rim, 10 feet off the ground.

Standing nearby is Russell Tillery, a member of Grant High School’s varsity basketball team who is known for his dunking ability. “Dude, what are you working out when you work out?” Tillery asks. “Because I need to start doing that.”

Whether it’s dunking or doing flips around campus, Accus, 17, is different than other athletes for more reasons than just his height. He is self-taught and because of his family’s history and faith in God, he approaches everything in his life with a positive outlook. He tries to stay optimistic, despite some of the challenges that have hit him and his family – his father leaving, a learning disorder and cancer.

“I don’t think of my challenges as challenges,” he says. “I just think of them as small barriers that I just need to work hard to get over.”

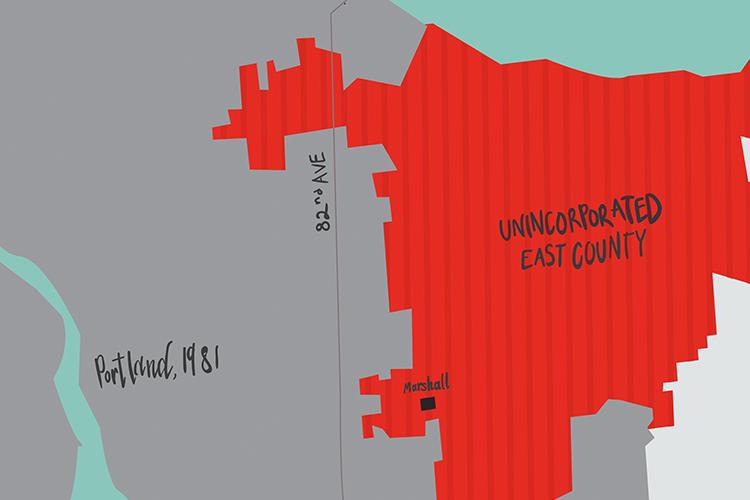

Accus was born in Portland on July 21, 1998 and grew up in Northeast Portland. “Back then, it was much more diverse than it is now,” he says. “I was surrounded by all types of kids: Russian kids, Romanian kids, Vietnamese kids.”

Accus is the youngest of three children. His half-sister, Ami, is the oldest, followed by his half-brother, Shawn.

As a child, Accus was primarily interested in getting out and being active, so he never needed toys. He spent a lot of his time going on outdoor adventures with his friends. One way they had fun was climbing trees. “We’d just climb up them, and then we’d see nests and stuff like that,” he recalls. “And then we’d just keep on going up and up and up until we (could) see the entire neighborhood.”

His acrobatic nature made him well suited for jumping and climbing. He remembers playing with friends who would try to jump onto the backs of moving vans for fun.

Accus was heavily influenced by the values of his mother, who came to the United States from Port-de-Paix, Haiti, seeking refuge. “It’s not easy,” says his mother Maritide Bonami, who left her life and country behind in 1994, eventually landing in Portland. She says she could no longer take the abuse by the Haitian military that she had faced for years.

She will never forget how she lost her house in Haiti. One day, while sitting at home, she noticed a few mysterious men dressed in camouflage uniforms standing outside her window. Bonami quickly left. When she returned, the house was burning, and all of her belongings were destroyed.

In the search for a new life, Bonami, who was pregnant with Accus’ brother at the time, met a sailor who provided a small boat for her and other refugees to reach the United States.

Once in America, life wasn’t much easier. She had to find a home, raise a family and get a job, all without being fluent in English.

But her story of struggle and perseverance left a powerful imprint on Accus. “I’ve learned a lot,” he says. “I’ve learned that stuff doesn’t come easy. I learned that you have to earn everything you get. You gotta work hard.”

In the third grade, Accus’ father left the family. It was hard at first, but Accus says after a while, the departure didn’t have a negative effect on the family. “By that time, I was about 8 or 9, and I was smart enough to know what to do and what not to do,” he remembers.

The Christian church also had a hand in shaping Accus. He remembers going to Bible study and participating in activities at his church. “It’s not like sitting there, actually studying a Bible,” he says. “There were actually lots of arts and crafts and games that we did, and then after all that they’d say, ‘Oh, the reason we did that is (because) that’s just symbolism for compassion.’”

But to Accus, Christianity is about more than just compassion. It’s a state of mind. “I feel like my faith and my religion helps me; it just keeps me moving forward,” he says. “That’s probably what keeps me on the bright side.”

As Accus got older, he developed a growing interest in gymnastics. In fourth grade, he joined Irvington School’s tumbling team. He had found a place to hone his skills. But after a few months, he was kicked off the team when a teacher accused him of threatening a fellow classmate.

“She didn’t tell me (I was) in trouble,” he recalls. “She didn’t tell me to go to the office. She instantly made a call and then told the principal that that happened. So I just feel like that’s very unfair.”

From then on, Accus dedicated himself to learning gymnastics all on his own. “I watched a few YouTube videos, and then the rest was just pure discipline,” he says.

He exercised as often as he could, never using the same workout routine twice. Accus climbed, jumped, flipped and ran all the time. He would engage in explosive training, which includes quick movements where muscles exert maximum force, also known as plyometrics. The “gainer” flip was one of his personal favorites, a flip where the acrobat does a backflip while running in a forward motion, going the opposite direction of momentum.

When Accus arrived at Grant High School in 2012, his athleticism stood out. The word spread about his impressive flips that he did around campus and his ability to dunk on a full size hoop.

But while his flips and tricks mesmerized people at Grant, Accus struggled in the classroom. He says he has a learning disability in math.

“It’s hard to focus in class. Like…someone with dyslexia in English class,” he says. “I can pay attention to the teacher and still not get a clear idea of what exactly they’re trying to instruct. But I just have to persevere through it, and I will pass that test; I will pass that quiz.”

His academic skills teacher, Mary Flamer, has noticed his dedication in the classroom. Despite his disability, she says that “He’s just amazingly focused…he’s one of the most focused of the seniors that I have,” she says.

“I don’t think of my challenges as challenges…I just think of them as small barriers that I just need to work hard to get over”- Angelo Accus

Last November, Accus was hit with another challenge. One day when he was returning home from school, his mother called him with some frightful news. She had been diagnosed with breast cancer. After comforting her over the phone, he remembers immediately sitting down to start his homework, still surprised. “I was shocked,” he recalls. “(And) the shock doesn’t really wear off; it just stays there.”

But he went on with his normal schedule, trying to not let bad thoughts consume him.

Liam Guthrie, a senior, is one of his closest friends. He said Accus told him about his mom’s condition, but that didn’t change how he carried himself.

“He just stayed positive,” Guthrie says. “He honestly didn’t change much. He was obviously always going home to help out his mom, and he seemed like he was spending a lot of time with her. But I think the biggest thing (is)…he just kept a very positive outlook, and I think that really helped, probably his mom, too.”

“What was going through my head was that I can’t let this stop me from doing what I do,” he says. “I can’t let this stop me from becoming what I want to be or developing into the young man that I’m going to be one day…If anything, it was only symbolism for me to push forward with life.”

Bonami has had to undergo surgery and months of chemotherapy since November to treat her cancer, but Accus says his mother has been steadily recovering with treatment. “She’s just changed from when she first started getting treatment,” he says, noting that doctors say her prognosis is good. “She knows that she has to push harder than she ever has.”

Today, Accus continues to stay active as it keeps him happy. Even though he doesn’t compete on a team or belong to a gym, he makes sure to always find time for fitness. “Every chance that I get, I’ll exercise,” he says. “I’ll never turn down a physical activity because that’s my happy place; it really is. Like climbing and stuff like that. Gymnastics, that’s what helps me find myself.”

Grant English teacher Mary Rodeback says Accus’ energy is captivating. During one of his class presentations, she recalls how he moved some desks aside and actually did a flip in the classroom.

“He’ll do that kind of thing every once in awhile,” she says. “He’s completely like the model student; quiet, organized, always on task, but then these things come out of him that’s like: ‘You’re incredible.’”

Accus hasn’t spoken to his father in about 2 years. His father has moved back to Haiti, and their communication hasn’t been regular. Accus’ friends say he speaks well of his dad but doesn’t mention him very often.

He prefers to stay positive about it. “He’s always been like a very heroic figure in my eyes,” Accus says. “He always just encouraged me to be friendly and just be nice. He always taught me that education is key.”

Accus doesn’t go to church much, and he hasn’t kept up with Bible study. But Accus says his faith remains. It’s helped shape his perspective.

“I’ve learned that stuff doesn’t come easy. I learned that you have to earn everything you get. You gotta work hard”- Angelo Accus

Currently, Accus works at Nike and, after high school, plans to attend Portland Community College where he’ll study kinesiology, the study of the human body’s physiological reaction to exercise. “That would just be a perfect fit for me,” he says.

He hopes to transfer to Portland State University and finish out his undergraduate education. Beyond college, Accus has noble aspirations.

“I want to pursue a career that is either in the medical or social field,” he says. “I want to help people that don’t really have like an equal opportunity. Because I just feel like everyone should get a fair chance whether they have a learning disability or whether they just have it hard at home.” ◊