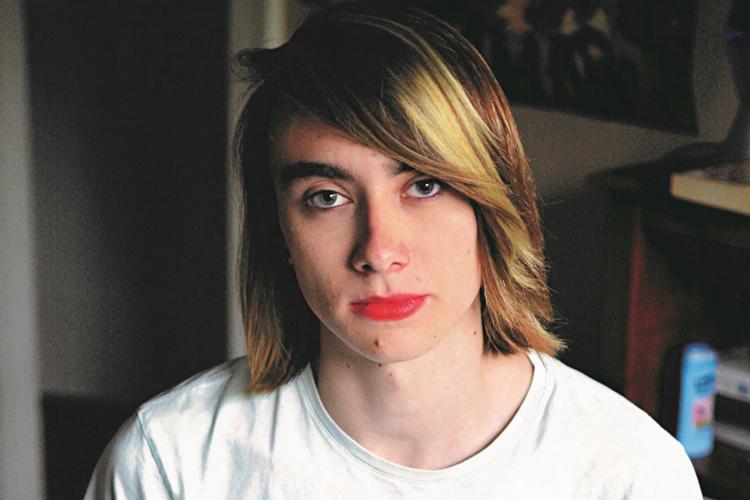

Born anatomically a male, Adi Staub spent 16 years living in a body that didn’t feel right.

With short brown hair, a deep voice and boys clothing, Staub passed under a false identity.

But midway through the current school year, Staub decided to stop hiding. After weeks of contemplation, the Grant High school junior slipped into leggings with shorts, straightened nearly shoulder-length blonde hair streaked with highlights and came to school feeling comfortable for the first time. It was a look she’d only ever worn in private.

Staub felt more like herself than she had all year. But anxiety clouded her thoughts. Long stares and confused looks followed her. People she’d been friendly with earlier in the year avoided her gaze. Her confidence fled as quickly as it had come. “I’m not passing,” she thought to herself.

Like many children across the country, Staub was born with an anatomy that didn’t match her gender identity. When she came to grips with being open about who she really was, it was both freeing and frightening.

“I really…hated being called a guy or being associated with doing masculine things,” Staub says. Growing up, she thought it was normal for children to hate their gender. “I just went my whole life thinking, ‘I really wish I was a girl,’ and I would dream up scenarios in which I would magically change into a girl. But that never happened.”

Today, Staub only goes by female pronouns and, for nearly seven months, she has undergone hormone therapy to physically align her body with her gender identity. She’s also in the process of legally changing her name.

“It’s…emotionally been like I’ve found myself because I had the wrong chemicals in my body for my whole life,” says Staub. “Now…I’ve finally been able to feel confident about myself and talk to other people and not just stay in my room the whole time.”

Despite her personal progress, Staub still faces hurdles in her day-to-day life. She says that many of her close friends from before her transition have dropped off the map, saying that association with her would “threaten their masculinity.” Since the beginning of the year, Staub has gone from skipping school intermittently, to only attending half of her classes a week, to not going altogether. Her motivation is at an all-time low, and school has become her last priority.

“I’m just trying to get through this year mostly,” says Staub, who stopped going to school a month ago. “I’m definitely at a point where I don’t care if I get all F’s in my classes; that doesn’t matter to me anymore,” she says. “I used to care like a lot, but transitioning has been infinitely more important to me.”

For transgender youth in Portland Public Schools and across the country, Staub’s experience is not uncommon. In Oregon, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students drop out of high school at a rate of 28 percent – three times higher than heterosexual students. According to a study conducted by the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and the National Center for Transgender Equality, an estimated 78 percent of transgender students experience harassment at school, and many seek refuge through alternative schooling or dropping out.

Across the country, transgender stories are increasingly being pushed to the forefront of news and media coverage as public transgender advocates, such as Laverne Cox and Caitlyn Jenner, continue to bring attention to the issue.

But even with that recognition, being transgender can create heat for others, even when it comes to the most basic of rights. During the current presidential campaign, there has been divided debate surrounding transgender worker’s rights, healthcare and whether it is appropriate for transgender people to use the public bathroom where they feel most comfortable identifying.

Still, many transgender individuals point out a disconnect remains between media discourse and ground-level awareness. Outside of the TV shows and political debates, many people who identify as transgender are left feeling isolated in school and work environments, which can lead to detrimental effects on physical and mental health.

At Grant, members of the openly transgender community – which is steadily growing – claim the disconnect comes from a lack of education and an uncertainty from peers and educators about how to appropriately address and support people who identify as such.

“I think we have some work to do,” says Grant Vice Principal KD Parman, who identifies as gender non-conforming but prefers female pronouns. “I think we have some work to do around a lot of different things in our education system and at Grant…It makes it really interesting and challenging, you know. As kids change, we have to constantly change and adapt. And how do we do that to help our kids feel safer and more included?”

Experts say that conversations around transgender narratives have been stifled because many are uncomfortable with unpacking what gender really means.

“I would describe gender as a culturally determined thing,” says Lisa Lowenthal, a local therapist who specializes in transgender counseling. “It is not something that is innate…it’s a culturally assigned belief that is not necessarily accurate…There’s a difference between someone being assigned their sex at birth and their gender.”

Sex, Lowenthal says, is biologically determined at birth based on anatomy, whereas gender is more of a deep-seated awareness of one’s self-expression.

“Transgender people have existed since humans existed in all cultures (and) in all histories,” says Christa Orth, a former professor of gender studies at Portland State University. She notes that, despite this fact, transgender people have yet to gain basic civil rights in the eyes of the law.

It wasn’t until the late 1970s that the first legislation appeared protecting transgender people from workplace, housing or school-based discrimination – and even then it wasn’t national.

Progress today, transgender advocates say, remains slow. In 32 states across the nation, it’s not against the law for businesses to fire or deny work to a transgender person solely based on their gender identity. Laws in North Carolina and other states continue to ban citizens from using public bathrooms that do not correspond to their sex assigned at birth.

And just last month, the governor of Mississippi signed a bill that allows businesses to refuse service to any person whose sexual orientation or gender expression violates predominating religious beliefs.

Grant English teacher Mykhiel Deych – who is the adviser of Grant’s Queer-Straight Alliance and identifies as queer – says discrimination against transgender people ultimately stems from fear.

“It can infuriate people when you don’t fit into one box or the other,” Deych says. “People get really mad when they feel threatened by the unknown.”

Elaine Walquist is the education program manager at TransActive, a non-profit organization based in Southeast Portland that provides information, activities and counseling services to transgender youth and their families. Walquist, who transitioned from male to female in her late twenties, says she has witnessed firsthand violence toward the transgender community.

“I met (transgender people) whose parents…tried to beat it out of them,” says Walquist of friends around the country. “In the 50s and 60s, people were put into mental institutions…because you had a ‘mental disease’…From what I’ve been told it was a terrible, terrible experience that does not alter their thinking at all.”

Lowenthal notes that because of the way misconceptions about the transgender community are perpetuated today, youth who are transgender aren’t given the language to diagnose common symptoms of gender dysphoria – a condition that describes the emotional and psychological disconnect between someone’s personal understanding of their gender and the sex they were assigned at birth.

Sam Punches, a sophomore at Grant who is transgender and prefers being referred to as they or them, experienced it at an early age. “I was always uncomfortable with myself,” Punches says. “I just didn’t really have a word to put to it. I don’t think I knew what transgender was until I was like 11 or 12…I kind of felt trapped because I wasn’t that able to be open about who I was…Being a teenager makes it hard. I guess I sort of felt in a cage.”

Grant senior Liam Posovich can relate. For years Posovich, 17, struggled with intense depression before realizing he was transgender. Born a female but currently in the process of transitioning, Posovich says he spent years trying to figure out the source of his anxiety to no avail. In September 2014, Posovich attempted suicide and was hospitalized for three and a half weeks. He says it took emotionally hitting “rock bottom” to figure out his true identity.

“I kind of stumbled across the term transgender,” remembers Posovich, who says he was sitting on his couch watching television when he had an epiphany. “I thought I was bipolar…but then I was like doing other research…and it kind of just clicked.

“The definition (of being transgender) is feeling high levels of discomfort in your body and feeling like something’s kind of off…feeling like you’re a different gender than you are…Being able to read all of that in a list, I was just like…that’s me.”

Since then, Posovich says his transitioning process has been relatively smooth. “I haven’t lost any friends. I haven’t faced any bullying at all,” he says. “I know that if anyone were to ever to do that there would be such a blowback from all of my friends.”

But Posovich recognizes his situation is unique among transgender youth. He notes that factors such as race and socioeconomic status play a significant role in shaping a person’s experience with coming out and transitioning.

“I think recognizing…privilege is super important within the trans community,” says Posovich. “Even the privilege of being a trans male instead of a trans female, being a white trans male instead of a person of color…recognizing how all of those things have made it easier to transition.”

Jaycen Montgomery, who is African American and identifies as male, agrees that recognizing societal privilege – or the lack thereof – is important. “I think that’s definitely something that…I wasn’t really aware of when I started my transition,” says Montgomery, who graduated from Grant in 2012. “Being an African-American male, especially during these times where police brutality with African-American males is very prevalent and very high…I’m viewed as more dangerous…less educated; ‘You’re a thug,’ all of that.

“Now you’re both black and trans,” says Montgomery. “Two minority groups. How do you deal with that? It’s hard in general…It’s just something that I’ve learned to kind of accept.”

In 2014, Montgomery garnered national media attention for allegations he made against George Fox University for denying his residency in male dorms on the basis of his gender identity. He says he had to fight the system every day. “George Fox being a conservative school, ‘transgender’ was not even something on their radar,” says Montgomery. “When I wanted to stay with males because I am a male…they were like, ‘No, you can’t do that.’ They said: ‘You were born biologically female. You need to be born a male.’”

Unlike George Fox and many schools throughout the country, Grant has made efforts to create a more inclusive space for students who are transgender. In the spring of 2013, Grant’s then-vice principal Kristyn Westphal spearheaded the creation of four unisex bathrooms, an administrative move that was prompted by the growing number of students who openly identified as transgender at the time.

“These students weren’t able to use the bathroom, and it’s important for students to be safe and comfortable at school,” says Westphal, who is the current principal at Hosford Middle School. “We need to make sure that we’re welcoming to all of our students and families and…if you can’t use the bathroom, it’s not welcoming.”

Last September, Grant’s administrative team led a staff-wide professional development workshop that focused specifically on transgender education. The aim, says Grant principal Carol Campbell, was to urge teachers and faculty to be proactive in reaching out to students.

“We incorporated…ways the teachers can better support students and families by…asking students what their preferred pronoun (is) and not assuming (and) informing people that students and families can change their information in Synergy,” Campbell says. “As a public school, we need to create the space for students to do that and be who they need to be.”

Many teachers say the event was helpful in advancing their knowledge around how to appropriately address and support trans students in their classrooms. Still, some say more research is needed to truly develop a solid understanding.

“If you have a student that has an identity that you don’t feel comfortable with…educate yourself. Read a book. Go online. There’s so much possible that we as educators can do for ourselves to become better educators,” says Deych. “I really think it’s our responsibility ultimately.”

Students also say the larger conversation around what it means to be transgender has been slow to trickle down. “It’s kind of like an awkward topic almost where I feel uncomfortable to ask, and I have questions that kind of sound stupid almost, so I don’t want to ask them,” says sophomore Talia Hope. “I hear a lot about it, but I still don’t know exactly what it is.”

For Staub, transgender awareness goes deeper than learning definitions and key terms; she says it takes a cultural shift. “Someone making a joke about a trans person being a masculine person trying to look feminine, that is honestly the worst thing for my mental state and other trans people’s mental state…because that’s making our lives a joke,” she says.

In 2019, when Grant’s district-funded renovation is set to be completed, the school will become the first school in the district – and one of the few high schools in the nation – to house communal genderless bathrooms. The final design for the bathrooms has yet to be finalized, but in each option the universal pants-and-dress icon will be replaced on bathroom doors with different signage.

Campbell says this redesign will continue efforts to justly serve students of all genders. “We’re creating spaces that actually give teenagers…the recognition they deserve to make good choices,” she says. “We have to do whatever we can here to make it better.”

Dana Brenner-Kelley is the chief executive of a local organizational consulting company called Leading Effect. Having worked closely with many transgender students in alternative schools throughout Portland, she notes there remains a discrepancy between theory and practice throughout Portland Public Schools – and across the country – when it comes to institutional education around gender awareness.

“I’ve been really concerned as a parent and as a community member that…there’s actually…a high risk for dropout amongst particularly trans students because we don’t have a system that’s supporting them,” says Brenner-Kelley. “One thing that I would love to see from the district perspective is to have an advisory committee of trans students (where they can) really impact what the education looks like for staff and for principals.”

Like Brenner-Kelley, Deych says there’s always more to do. “Things like (transphobia) are not absent from our culture at Grant, and they’re not gonna be absent just because we keep saying they are,” says Deych. “The only way they are going to be absent is actually if we keep dialoguing about all of it. If we fully train the staff on all forms of diversity and equity and if we have real protocols in place on how to respond when issues arise.” ◊

Grant Magazine reporter Sarah Hamilton contributed to this report.