Stories by Alyssa Goessler

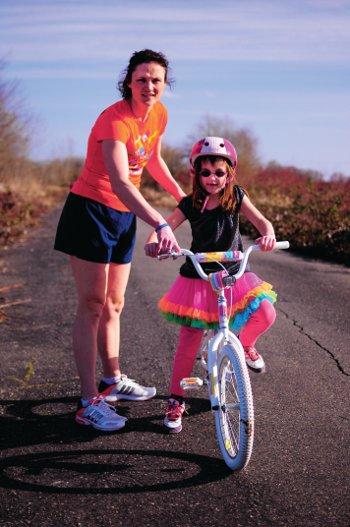

Photo Courtesy of Suzanne Polen Mann

On the south side of Grant High School near the roundabout at Northeast U.S. Grant Place and 35th Avenue, a small and somewhat overgrown garden is opening up with the spring rains. There’s not much variety; a few sparse bushes with flat green blades grow untamed. Three tall evergreens tower above it. The garden looks worn, with bike tracks appearing at its edges and some garbage tossed on top.

Yet at one edge, a victorious bush has pushed through a barrier of weeds, its small yellow blossoms lighting up the aged garden with brilliant color. Atop a foot-wide concrete box in the center of the garden sits a metal, engraved plaque that reads: “Betty’s Garden. Betty Polen – Grant Teacher, Neighbor and Life-Long Friend of the Children. March 24th, 1917 – May 7th, 2001.”

The name Betty Polen rings few bells with those in the Grant community. John Mears, one of the track coaches and a history and special education teacher, went to Grant and graduated in 1970. He’s taught at the school for 26 years but has no clue who Polen is. He remembers when the garden went up in 2001.

Sophie Montgomery, a senior at Grant, was on the girls soccer team and played near Polen’s memorial for years. But it never caught her eye. Even Toni Hunter, the principal who was here when the memorial was erected, didn’t know of Polen.

Greg Thoming was a six-letter athlete who graduated in 1977. After high school, Thoming joined the U.S. Air Force Academy. In October 1978, Thoming was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis and was hospitalized. His dad told him lay low but Thoming wanted to get back to the academy. After returning, he collapsed and died from cardiac arrest and bleeding in the colon. His twin brother, Christopher Thoming says: “He was so ready to become his own person. Our parents were devastated. You never plan to lose a child.”

His family started the Greg Thoming Memorial Fund, which resulted in a trophy case. “It was the principal’s idea to have the trophy case,” Christopher Thoming says. “Obviously, it has done its job because we’re talking about it right now.”

Polen, as it turns out, was a pioneer for the Portland Public School District. She worked for the district from 1955 into the late 1970s and was known from the start as a champion of children’s health and fitness. She later became quite rogue in her pursuit of healthy lifestyles, pushing for the acceptance of then-taboo subjects like sex education. Her story and the plaque in her name are reminders that Grant has a treasured past of people who have contributed to the school’s legacy and beyond.

Betty Riesch was born in 1917 and grew up during the Great Depression. Her childhood was anything but easy. Throughout high school, Betty worked a job to help pay for her older siblings college tuition. She only had two dresses to her name: one to wear and one to wash. She went to the University of Oregon and earned her undergraduate degree in physical education.

Money was tight. Letters she wrote to her parents at the time show how grim things were for her. She wrote about having to take apart old pieces of clothing to fashion them into new garments to wear. A bright spot in college came when Betty met the love of her life, Richard Polen.

“The two had quite the love affair,” recalls Betty Polen’s oldest daughter, Suzanne Polen Mann. “Apparently, Richard was absolutely dashing, and he did everything larger than life.”

They married in August 1943 and moved to San Diego where Richard was stationed with the military. They lived on a half-acre plot, which Richard promptly filled with a vegetable garden. Suzanne was born in 1945. Patricia came along five years later, a month before Richard was sent off to fight in the Korean War.

“It’s one of my earliest memories – my father pulling away in the car with tears streaming down his face,” Polen Mann recalls.

Betty and Richard wrote to each other for the first three months of the war. But then the letters stopped coming. Richard was lost in action. “We were in limbo for three years,” Polen Mann recalls.

The metal plaque in front of the school has a list of 107 names.. The memorial, created by the Colton Meek Hi-Y Club in 1955, is “dedicated to the gallant men of Grant who died in the service of their country.” The list includes Wallace Zosel, a graduate who lost his life in the Battle of Normandy. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart. Or there’s Malcolm Hutchinson, who graduated from Grant in 1940 but his life in the Philippines on a training flight in 1946. Grant teacher John Mears, Class of 1970, sees the memorial as a reminder. “The power of memorials is more for the living than for the dead,” says Mears. “When there isn’t constant energy behind a memorial, it loses its significance.” Most people are too busy to notice but it’s not lost on Mears. “When I see kids staring up at the sports pictures in the halls, its like history is coming alive for them,” he says.

There were many prisoner of war camps in Korea, and the family could only hope that he would turn up when the war ended. Polen, meanwhile, was stretched thin with two girls and an overgrown garden on her hands. She moved back to Portland. Richard Polen was declared dead when the war ended three years, but his remains were never found.

Betty Polen struggled to raise the girls by herself. In the 1950s, single mothers were not as common as they are today, and Polen had to overcome many hurdles. At the time, getting a loan to purchase a house wasn’t a common occurrence for women. “She had to twist a lot of arms,” Polen Mann recalls.

Polen gained the trust of one banker and managed to get a loan to purchase the house at 3546 U.S. Grant Place. Then she settled in and began to fight for a job. She was a born teacher and loved children, but women stereotypically fell into the role of housewives. Polen needed the money.

At age 38, she applied at Grant High School to be a physical education teacher. The principal at the time didn’t want to give her the position, saying she was too old to be a physical education teacher. He did not know Betty Polen.

Polen was dedicated to health and fitness before it was popular. Her daughters recall being the only kids at school who had sandwiches made with whole-wheat bread. “She was a stickler about eating something green every day,” her other daughter, Patricia Polen recalls. “Back then, it was just a lot of meat and potatoes.”

Betty Polen got the job. She loved the school but the district had other plans. She was promoted in 1957 to director of health education for the district. In the 1960s, she was given the task of introducing sex education to the district. It became her passion. She led discussions about sex-education on radio shows and at Parent-Teacher Association meetings. She traveled all over the state to make presentations. In California, a coalition against sex education was formed and members bussed to Oregon whenever they caught word of a meeting on the topic. “She dealt with a lot of screaming, outraged people,” Patricia Polen recalls.

Claire van Engelen and Andrea Perez couldn’t wait to get to the Oregon Coast in the summer of 2004. They were about to start their senior years at Grant. According to news reports, the car Van Engelen was driving hit speeds over 100 miles per hour as it descended down a treacherous curve heading toward Seaside. They lost control and slammed into a delivery truck headed the opposite direction. Both girls died and the incident shocked the Grant community.

That year, the seniors raised money to build two memorial benches that sit in front of the school in honor of the girls. The small placard atop the benches reads: “In Memory of Claire van Engelen & Andrea Perez, 1986-2004. Donated by the Class of 2005.”

Steve Duin, the Metro columnist at The Oregonian, wrote a column about the crash. He wanted the column to send a message to parents and teen drivers. He wrote about finding one of the car’s hubcaps at the scene of the accident and hanging it in his garage. “When your kids are out, every time you hear a police siren in the distance, you get that urge to reach for your cell phone,” Duin says now. “I hope the fact that I still have that hubcap in my garage memorializes them in some way.”

Polen led some of the first discussions on homosexuality – a topic that she attempted to include in public school curricula. She was a member of a Governor’s Task Force on Sexual Preference. This group, which included some gay and lesbian parents, worked together to discuss and audit how the subject was being presented within schools.

Later, Polen became involved with public health and safety issues. She fought for awareness around child abuse, a taboo topic that was almost entirely ignored at the time. Rather than asking people to focus on strangers, she adamantly encouraged people to pay close attention to family members and friends, as they were the most common committers of sexual abuse.

In some cases, Betty Polen’s passions had no boundaries. Polen Mann remembers her mother’s insistence that people pay attention to issues like overpopulation. One night, she brought the topic up at a dinner with a family of seven. No family should have more than two children, she told the family. “My sister and I just wanted to crawl under the table,” Polen Mann recalls.

Polen Mann recalls her active mother swimming a few times a week. Around the neighborhood, she was known as everyone’s grandmother. Children often came to her door to ask if she could come outside to play, her children remember. She baked with kids, did art projects and taught children how to tumble and do other gymnastics moves in the backyard. She hosted birthday parties for neighborhood dogs and was frequently seen biking around the neighborhood with her own pets in tow. “It was kind of embarrassing during high school,” Patricia Polen recalls. “She was a bit rogue.”

In the 1980s, Polen was diagnosed with breast cancer. She beat it for a time, but it returned. She died in 2001 with her daughters by her side. That’s when a group of neighbors came to the door and proposed creating Betty’s Garden.

The garden has been around for eleven years. Every spring, the plants come back. They are untamed, but alive nonetheless. In many ways, the garden serves as a symbol of her legacy, representing the ability to overcome whatever life throws at it.