Story by JJ Miller

Photos by Salem Carrico-Rogers

Every night, Leo Rhodes can go home to a place of his own. He can sleep through the night without waking up in fear. He no longer worries about finding his next meal, hiding things from his boss or racing around to find a place to sleep.

Six months ago, this would not have been possible. Rhodes was homeless and had lived on the streets for 19 years. And like the more than 3.5 million others who wind up on the streets on any given night, Rhodes was in crisis.

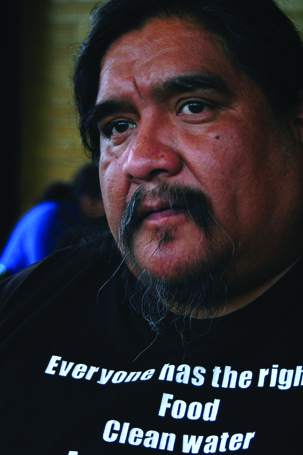

“People don’t understand how hard it is and what you have to go through on the streets,” says Rhodes, who is known in the Grant community for perching outside of Whole Foods on Northeast Sandy Boulevard and selling Street Roots newspapers to passersby.

Today, with the help of a Portland City Commissioner, social service agencies and the Street Roots newspaper, Rhodes has managed to get back on his feet. He’s free of the drugs and alcohol that had previously wracked his life. And he wants to make a difference for others.

“Leo is hard to miss because of his involvement in advocacy,” says City Commissioner Nick Fish. “He is very social and personable. He does not hold back.”

Given today’s economy, the number of people ending up homeless has skyrocketed. More families are living paycheck to paycheck and affordable housing is becoming harder to come by. For Rhodes, his odyssey to Portland began early on.

He was born in the 1960s on the Gila Indian Reservation near Phoenix. He doesn’t talk about his exact birthday and he doesn’t celebrate it. He was born to a young couple that put him up for adoption.

When he was six years old, Leo and Marie Rhodes adopted him. He says growing up, his family and friends were using alcohol, drugs and fighting as an escape. His parents used to drink heavily every night and never asked him about school. His grades suffered as a result and so did his choices in life.

In middle school, Rhodes started experimenting with alcohol and marijuana.

“Nobody ever told me what I should and shouldn’t be doing,” he says.

But Rhodes knew one thing about his future: as soon as he turned 18, he was going to enlist in the Army. He wanted to be an infantry soldier so that he could get as far away from the reservation as possible. “I didn’t look up to anyone when I was a child but the Army gave me something to look forward to,” he says.

His unit was stationed in Berlin in the mid 1980s. Having been independent his whole life, the Army gave Rhodes satisfaction in knowing that he was on his own but also a part of something greater. “Leaving the reservation was the right choice for me and I was finally doing something with my life,” he says. He served in the Army for three years.

In 1988, Rhodes came back home to the reservation. He fell in love with a woman he met through a mutual friend. “We hung out a lot and we joked around with each other all the time and we were really happy with it,” Rhodes recalls. “I loved her.”

One night, while driving down a muddy road on the reservation, the car she was driving went out of control and off the road into a canal. She was unable to get out of her seatbelt and drowned on the scene. “I didn’t understand how someone I cared about so much could just be gone in an instant,” he says.

After her death, Rhodes fell back into old habits: drinking and doing drugs.

“I kept thinking about how nothing was going right on the reservation,” he remembers. “I couldn’t find any friends who weren’t using and I could not escape the sadness. Everything was just building up inside the reservation and I couldn’t take always being surrounded by it.”

In 1992, he left the reservation and hitchhiked up the West Coast to Seattle. He found a job as an assembly worker, but didn’t have a home. The homeless shelters were closed by the time he left work, leaving him with one option: the streets.

Each night was a gamble. He never knew when a teen would kick him in the head or when someone would steal his belongings or when a person next to him would die because of the cold. He never had a full night’s sleep. “I had to wake up every 20 minutes to circle the block and make sure I was safe and then try and fall back asleep,” he says.

He was constantly going back and forth between factory jobs. He would hide his bags in the break rooms out of fear that his bosses would see he was homeless.

In 2000, after being homeless in Seattle for eight years he decided to go back to the reservation to see if life had gotten better for his family.

Three weeks after he got back to the reservation, his father was in the hospital on life support. The drinking had finally caught up with him. Rhodes’ dad had previously told his son what he would want to happen in such a situation. Rhodes ordered the doctor to pull the plug.

A few days later, Rhodes was at home when he heard gunshots. He assumed that his nephew was just shooting his gun off next door. But Rhodes’ brother came sprinting over to his house and told him that his nephew had been shot nine times. A rival gang member was the assailant.

The day before, Rhodes’ nephew had told him he wanted out of the gang life. Rhodes had promised to help him.

By winter 2001, Rhodes had had enough. “I was tired of all these heartbreaking events on the reservation,” he says now. “It seemed to always be that way and it was depressing all the time.”

Rhodes moved back to Seattle, finding himself homeless again. Tired of being neglected, he decided to become an advocate for homeless people. With a few close friends, he helped start Tent City 4, a community where the homeless could live safely. It took more than a year to get approval but the responses from the community was supportive.

But the idea was a political hot potato for the politicians. Rhodes organized community meetings where the concerns could be shared, but the focus often shifted to drug and alcohol use. “I just kept fighting because I could not tell the homeless community that they didn’t have a home,” Rhodes says.

Tent City 4 was finally created in 2004. While advocacy was Rhodes’ passion, supporting so many people without a break was tiring him out. He was in and out of meetings every day, trying to find a better place for the encampment. After five years of living in Tent City 4, he decided it was time for change.

He moved to Portland and started working again, this time with elected officials. He found a friend in Fish.

When he saw the rising homeless issue in Portland and the lack of strong advocates, he knew that he had to do something. The city suddenly heard his voice.

Fish recalls many times when Rhodes showed up at City Council meetings and stood up to voice his opinion. “Sometimes he will sit quietly in the back with a shirt that speaks to the rights of the homeless,” Fish says. “Other times, he will stand up and tell the stories of homeless people that put the stigma to bed.”

After living in Portland for three years, Rhodes finally got an apartment he could call home through the Veterans Assistance Housing Project; he had been on the waiting list for more than a year. “At first, I didn’t believe it was true,” he says. “I asked the building manager if it was a joke and half expected them to have some complication that would prohibit me from getting the apartment.”

It was a furnished unit with just what he needed: a bed, a rocking chair and a table with two chairs. “It’s the way I like it. I don’t want anything that I don’t really need. I am still getting used to having a place,” he says.

Rhodes has not stopped fighting and advocating for the homeless even though he has a home. He founded Right to Dream Too encampment on Southwest Fourth Avenue and Burnside Street, a homeless community with a semi-permanent living area that people can come in and out of.

He’s writing a book about his experience being homeless. He is also making a documentary detailing the fight of starting Tent City 4. His only income comes from selling Street Roots, where he’s been a regular fixture outside of Whole Foods.

He writes a column in the paper from time to time and says he’ll continue to be an advocate until homelessness is eradicated. Leo, Fish says, “is giving voice to the voiceless.”

“I won’t stop,” says Rhodes. “Nearly 2,000 people sleep on the streets each night in Portland and they need someone to stick up for them.”