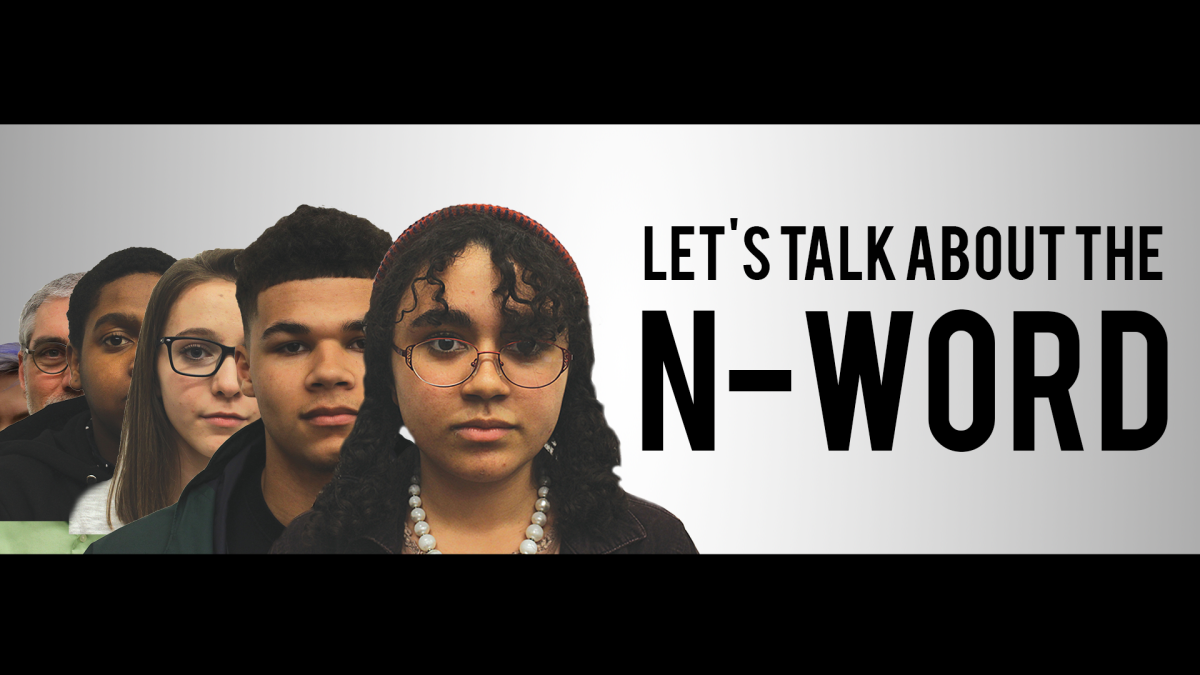

Last year, when seven white Grant High School freshman boys posted racist and misogynistic photos and comments to Instagram, amongst the degrading remarks were “nigger” and “nigga.” Fast forward to early November, when the Grant varsity boys soccer team came under fire for comments players made using the racial epithet.

You’d be very wrong if you assumed these events were isolated or rare. They speak to a greater disconnect at the school that the administration has yet to confront, though they have plans to. Grant’s equity team is trying to figure out how to start a meaningful discussion on race. But the process is being far too drawn out.

A number of things have come up as obstacles for the start of these discussions, mainly planning snags and the lack of a timeline. Right now, the talks are set for mid-March instead of the initial January date. This delay speaks to Grant’s normalized culture of racial ignorance.

It’s disturbing, the number of hurdles that continue to get in the way of understanding the role race plays in our everyday lives – namely, the fear that is associated with talking about it.

Our school’s staff is not equipped to moderate conversations on race because in the past, they haven’t been held accountable. This prompted Grant’s equity team, in tandem with a select group of students who have been meeting weekly, to seek outside resources to help with the upcoming schoolwide race talks.

We respect that the administration is pulling in outside personnel because if the school is going to do this, do it right. It’s heartening that thought and consideration are being put into the discussions, but the process sheds light on some of Grant’s lesser known issues that contribute to the social segregation – and inherent isolation – we’ve seen on campus.

Among the chief issues is Grant’s staggering under-representation of minorities when it comes to the adults at our school. With 125 members on staff, nine are black, and only one of those is a teacher. And there are very few other non-white teachers.

This year’s freshman class has 36 black students out of a total of 396. And the population of students of color has been dropping steadily over the years.

Those figures make discussions difficult. But they also show the gaping hole we are dealing with at Grant when it comes to race. How can we have honest conversations when the numbers are so skewed?

In the past when issues of race came up, the administration appeared to avoid the topic, citing confidentiality around student discipline. Yet, when kids rampantly use the N-word in the halls and in classrooms, you can hear the crickets chirping when it comes to the school’s collective reaction.

We’re not suggesting focusing all our attention on one word that has a history of racism buried within its core. What we are saying is that we need to talk more about everything associated with the word. This means starting those conversations early on and then providing resources and platforms for students of all backgrounds to recognize one another’s histories.

A glaring example is that we have only two culturally-specific classes, Living in the U.S. and African-American Literature, at Grant. That’s not nearly enough to shed light on the multicultural perspective.

The demographics in those classes are considered anomalies when you look at the whole of Grant High School. In these courses, minority students make up the majority. Part of this lies in the concept that these classes are really the only two that recognize black history and the multicultural narrative, rather than just an obligatory nod in the core curriculum.

Because of this, we want to see a commitment from the administration to unsubscribe from the majority culture that occupies classrooms and the hallways. We want to see teachers facilitate effective conversations so it no longer takes five months to plan for a 90-minute discussion.

The N-word is used every day by people of all different backgrounds with both friendly and hateful intentions. This issue of Grant Magazine extends beyond the discussion of the N-word, in all its uses. To us, it’s about much more than the word.

As students, we tend to take words lightly. We throw around curse words that, as children, we were shamed from saying by our parents. The N-word does not fall into this category. In fact, the N-word really doesn’t fall into any category.

Collectively, as a staff, we don’t see a place for using the word in today’s society. We’ve done our reporting for this issue, talking with students, staff and a host of experts. But before we got that far, we had to do our own research. How could we speak authoritatively on a subject so complicated without understanding its power ourselves?

In our interviews, we’ve recognized certain trends. There are non-black people who avoid the word at all costs. In fact, many Grant teachers find themselves in this category. Then there are the non-black people who find it appropriate to use the word in both a derogatory way and what we consider to be superficial.

Within the black community, it gets more complicated. Some make a case for reclamation of the word in an attempt at diluting the historic weight through its use. Others recognize that the word’s history is too vast and painful to divorce.

There are arguments for each of these outlooks, less so for the non-black people who think it is OK to use the word regardless of intention. And not everyone falls into these groupings definitively.

But our staff does: the history and the impact are too great to ignore. Beyond that, how can a word be reclaimed if its history is not understood? And how can its history be understood if there are no conversations? ◊