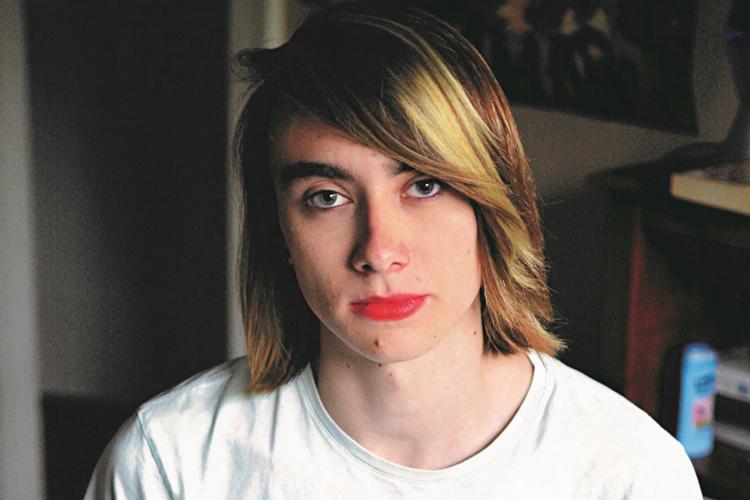

Five minutes into jazz legend Duke Ellington’s hardest piece, Tattooed Bride, Grant High School student Olivia Gadberry recalls standing up for a solo. The bright stage lights glint off her trombone as she draws the attention of everyone in the crowded New York City concert hall.

She takes a deep breath and stares straight ahead, her initial nervousness replaced by excitement. It’s hard not to notice the stark contrast between her formal black dress and the sea of white tuxedos worn by her mostly male band mates. But her musical ability as a member of the American Music Program’s Pacific Crest Jazz Orchestra brass section makes her distinctive in another way. Her sound commands attention.

Those lucky enough to be attending the Essentially Ellington High School Jazz Band Competition held in Lincoln Center that night could barely draw in a breath when they heard how the song was played.

“You have to understand something,” says Todd Stoll, vice president of education for jazz at Lincoln Center’s Essentially Ellington program. “Tattooed Bride…It’s a masterpiece. It’s like Beethoven’s 9th Symphony or Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony. There is not a lot of work in jazz repertoire that you can call masterwork and this is one of them.”

Gadberry, then a freshman, had recently joined the group that is referred to by its musicians as AMP or P-Crest. She was among the musicians as they sophisticatedly navigated the song’s advanced harmonic language and nuance of phrasing.

She says her immersion into the demanding and competitive world of jazz has helped her grow out of her shyness to become stronger and more independent. It’s something she’ll need in the future if she wants to survive in the male-dominated field.

As a woman who plays jazz, Gadberry will need to clear some hurdles to succeed, says Hailey Niswanger, a female saxophonist and composer from Portland. “There is kind of a general assumption…that females don’t play as well as males.” Niswanger says. “You really need to be able to back up the fact that you play in order to be taken seriously.”

“People say, ‘Oh, you’re so good – for a girl.’” – Olivia Gadberry

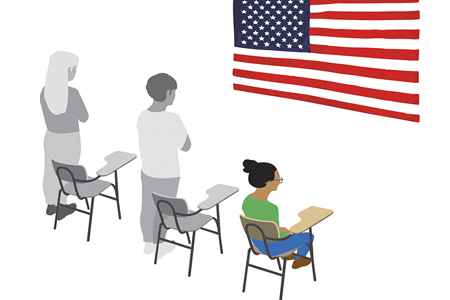

According to a report published by the National Endowment for the Arts research division, there’s a gender disparity in jazz – with seven of every 10 performing musicians being male. At music festivals across the country, the musical lineups exhibit an even more striking gender imbalance. Many bands have women as vocalists. But there are few female instrumentalists and even fewer headlining or main stage female performers.

In the San Francisco Bay area, the numbers of female instrumentalists performing in festivals last year were alarmingly low. The 2014 San Francisco Jazz Festival had only two female instrumentalists in headlining roles out of 21 featured acts. And at the Stanford Jazz festival, only five of the 35 acts featured lead female instrumentalists.

But Gadberry is ready to tackle the odds.

“There has never been a time when I didn’t want to work for it,” she says. “People will laugh at you and think you are a joke just because you’re a woman. But if you are really good, then you can show people you deserve respect.”

Gadberry was born in San Francisco on Apr. 11, 2000, and moved to Portland shortly thereafter. She’s the younger of Liz and Mike Gadberry’s two children. Her older brother Isaac, 17, is a junior at Grant.

Growing up, Gadberry was just a normal goofy kid, her mom recalls. On her daughter’s fourth birthday, Liz Gadberry remembers getting Olivia a unicycle.

“Someone would ask, ‘Where’s Olivia?’” remembers Liz Gadberry. “And she would be out front teaching herself how to ride.”

She fell a lot, getting her share of bruises and scrapes. But her persistence paid off and she learned how to handle the one-wheeled contraption.

No one in her family had any musical talent so it surprised her mom when Gadberry came home from Irvington School one day in fourth grade, begging to take clarinet lessons.

That day, the group called Musical Understanding through Sound Education had performed at the school. Their shiny instruments and powerful sound, Olivia Gadberry remembers, left her feeling impressed.

“I was amazed,” Gadberry recalls. “I didn’t know people could play instruments that well. They were probably just middle-schoolers or something, but I thought they were super cool. So I wanted to play.”

She was motivated, but her shyness nearly stopped her from joining the program. “I have always been the type of person who wouldn’t go to camps if I didn’t know another person there,” says Gadberry.

So when her best friend, Sadie Thorburn, picked up a clarinet, Gadberry did too. “Olivia has always been a kid who if she’s interested in something, she will work really hard at it,” says her mom.

Gadberry dabbled in soccer and played on a club team, but music was becoming her focus. In sixth grade, she played in an entry-level band at Beaumont Middle School. She dropped clarinet in favor of the trombone, as did Thorburn. And by seventh grade, the girls had progressed to the advanced jazz band.

Cynthia Plank, the band director at Beaumont, remembers that the two girls stood out. “First of all, it’s unusual for girls to play trombone,” Plank says. “They just kind of moved to the front of the pack pretty quickly.”

As a band director, Plank tries to encourage girls to pursue jazz music because she feels there are not enough women participating.

“I think girls need to see a woman directing so they can imagine themselves as a band director,” she says. “They need to see women playing jazz so they can see themselves as successful jazz musicians.”

Despite her efforts, Plank says the bands she leads are not always gender balanced. A lot of girls start out, but many don’t progress on to the more difficult levels. “In the beginning, I’d say 60-40 boys to girls,” she says. “And as it goes on right now, like in the eighth grade band, there are a lot more boys.”

It happens early on, Plank says, when students pick instruments. Jazz instruments are traditionally thought of as masculine.

“For the longest time, I think parents and teachers steer girls towards clarinet and flute, and maybe if they’re really cool, saxophone,” she says. “Girls don’t play drums, boys play drums. Boys play trumpet. Boys play tuba. I think parents say that and they don’t even hear what’s coming out of their mouth.”

By the time the pair reached Grant their freshman year, they were selected as members of the primarily upperclassmen Jazz Ensemble.

Quin McIntire, now a Grant senior, noticed their ability right away in Jazz Ensemble. He was a member of AMP and knew his director, Thara Memory, was always looking for female musicians.

“I told them to come in,” McIntire recalls. “They had potential. When you see that, you definitely need to follow it.”

Nationally recognized, AMP is a leader in teaching high school students about jazz. Notable alumni include the Grammy Award-winning Esperanza Spalding and saxophonist Niswanger.

Memory wants to shift the playing field. He works hard to empower young women and minorities to succeed in jazz. “I teach these guys because I want them to change the world,” says the award-winning director. “I’m tired of it the way it is… everybody should be equal.”

The first few rehearsals with AMP left Thorburn and Gadberry feeling intimidated. The band had a different tempo than anything they had experienced before. “I was in the band for six days,” Thorburn recalls. “And within those six days there were five practices.”

Thorburn remembers thinking it was too much of a time commitment and eventually stopped going to rehearsals.

That’s when Gadberry realized she had a choice to make. Being shy, she didn’t know if she wanted to continue in AMP without a friend. Already, she was among the youngest in the band and felt intimidated by the skill levels of the other musicians.

“I thought I needed her in the band with me,” Gadberry says. “Then I realized it would be a stupid mistake to quit this band. I was already impressed at myself that I was able to be in it.”

McIntire plays baritone saxophone in the band and was glad she stuck with it. “She’s shy, but what she brings to P-Crest is a sort of diligence about playing her instrument,” McIntire says. “When she plays her horn, it’s loud. It’s really her.”

Located at King School in Northeast Portland during the school year, AMP rehearsals always ran longer than their planned two-hour time frame. In her own time, Gadberry was practicing and listening to jazz, leaving no time for soccer.

“At first, I wanted to keep playing soccer, but now not really,” she says. “AMP is kinda just like what you do. There is nothing I would rather be doing.”

Everything was going well in the band for Gadberry as the dates of national jazz competitions neared. Connections between her and the other musicians were forming. Weekly rehearsals became more frequent, increasing to every day before the Charles Mingus High School Jazz Competition in New York City and then the Next Generation Jazz Festival, in Monterey, Calif.

At both, AMP blew away its competition, placing first and second, respectively.

After the competition, Gadberry noticed something that she’d thought about but hadn’t experienced before; there were some prejudices against women in jazz. “People say, ‘Oh, you’re so good – for a girl.’” Gadberry recalls. “Some people learn that I play jazz and are like, ‘Oh, are you a singer?’ No, not every girl in jazz is a singer.”

The comments made her angry at first, but she learned to brush them aside. She practiced harder and focused even more.

Months earlier, AMP had submitted a recording of the bands’ music to the Essentially Ellington competition. Eighty-eight bands applied to compete at the May 2015 contest, and AMP was selected as one of the top 15 finalists to go for the grand prize in New York City. It’s an annual high school jazz band competition and festival where bands from across North America travel to compete.

“A ton of rehearsals were just dedicated to playing Tattooed Bride,” Gadberry recalls. “I can’t even tell you how many times I have played that song.”

Not only was the piece 13 minutes, almost three times longer than other scores available to the competing bands, but AMP also memorized the song.

“I come from a culture of ‘learn how to read extremely well and forget it,’” says Memory. “And that’s not where the music is if you want the music to touch your heart and stay there for a long time.”

Memory has his band memorize music instead of reading from sheets, which makes the musicians really internalize the music, Gadberry says.

When the day of Essentially Ellington finally arrived, and AMP landed in New York City, the feeling, Gadberry says, was indescribable. “Before, I was terrified,” she remembers. “I was playing in front of all these jazz legends like Wynton Marsalis. But when I was playing…I was in that place where you don’t have to worry about anything.”

All of their work boiled down to less than 20 minutes on stage.

For Gadberry, her solo was a high point. “She played a big solo, big deal, at Essentially Ellington, you know for a freshman in the band,” McIntire says.

“I remember her specifically,” says Stoll, who was in the audience that night. “The amount of feeling she played with was way beyond what you would expect of a young person her age. She played with a kind of security and then she kind of brought this soulfulness to her performance.”

When the last notes started fading, the audience erupted into a five minute standing ovation. Wynton Marsalis judged their performance and all he wrote on their scorecard was: “I didn’t believe it, but I saw it.”

“Wynton and I never thought we would see a high school band play the Tattooed Bride,” says Stoll. “Literally, we had tears in our eyes. And they played it from memory. That just blew our minds.”

AMP won first place, and for her trombone solo, Gadberry was recognized as an Outstanding Soloist.

Out of six trombone players, she was one of two females to receive the distinction.

Stoll recognizes the small number of women and girls in jazz. Overall for the competition he sees bands with about a 60 percent to 40 percent male to female split.

But the numbers in the bands that make the finalists’ list paint a different picture. The two bands who placed after AMP had mostly boys who performed. Even AMP had only four girls at Essentially Ellington, out of a total of 17 musicians.

This makes the young women participants stand out. And not always in a good way. “It’s hard sometimes because there aren’t many girls,” says Gadberry. “Some people have prejudices.”

Even the pros see it. The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, one of the world’s leading big bands led by Wynton Marsalis, has never had a permanent female member in its 28-year existence.

“There’s definitely sexism in music,” says Niswanger, who’s made playing jazz music her career. “It’s there.”

Gadberry says she has grown used to sexist remarks meant as compliments. “People will make comments like, ‘The most beautiful trombone section,’” says Gadberry. “They always comment on it. We understand that we are girls and we play trombone.”

AMP’s Thara Memory has seen it all. He’s taught jazz to students and adults in a lengthy career. He’s seen as a legend in Portland jazz circles. At 68, his health is failing.

He has diabetes and it’s cost him part of his leg and a number of fingers.

But his ailments don’t stop him from recognizing that a change is needed. He says he’s heard directors say to women or girls, “‘Wear that short dress. Wear your high heels…You ain’t coming on this bandstand without high heels.’”

And this is one of the problems for female jazz musicians. “You really do have to prove yourself beyond people thinking that people are coming to see you just because you are dressed in a pretty dress,” says Niswanger. “I definitely think that there is some shade thrown toward the way of women. We’re not featured as much as men because there is just this presumption that we don’t play as well.”

Memory says he tries to prepare his female musicians for a successful career in jazz, all the while drilling into all members of his band that equality in jazz is a priority. “What I’m doing here is revolutionary,” Memory says. “I’m teaching social justice.”

Stoll recognizes this, as well. “Jazz has not done a great job of cultivating young female performers,” he says. “So we are very interested in making sure that women have opportunities. We host a girls’ jazz day here at Jazz at Lincoln Center.”

In the Essentially Ellington competition, things are starting to change. Stoll has seen the number of young women participants rise over the past few years. “Actually, last year we had one band that was majority female,” he says. “We are definitely seeing an increase in that.”

Locally, Plank says female jazz musicians are also becoming more prominent. “Do they have to be better to get an audition? Maybe,” says Plank. “But in Portland, there are a lot of women who can really, really play.”

In other professional big bands, the use of blind auditions to combat possible biases in hiring is becoming more widespread. In blind auditions, a screen conceals the identity of the candidate who is trying out. It’s a technique that was used by symphony orchestras in the 1970s and 1980s with great success.

In 1970, the number of women in the top five U.S. symphony orchestras was less than five percent. Today, the number has increased to about 25 percent. Many say this hiring technique will work in jazz as well.

At a recent afternoon rehearsal, Gadberry sits in a blue folding chair, chatting with two girls. They all have their trombones held in their laps. Now AMP has four girls and an all-female trombone section.

Memory has just stopped the band, hearing something that he didn’t like come from their horns. “You gotta play twice as good as them boys right there to get the same job,” Memory reminds them as he gestures at the all-male saxophone section.

For many in the band, a career in music is the dream. Gadberry wants to attend a music school in New York City after high school. She understands the hurdles out there for women in jazz, and someday wants to break them down.

“There’s not any one woman that can carry the torch,” says Niswanger, who mentors young female musicians to help them progress in jazz. “For us to change the stereotype and (for) women (to) want to play, then great, they should. And they should really throw down when they do so.”

Eventually, Gadberry says, her part in breaking gender barriers includes teaching and encouraging more girls to become jazz musicians.

“I think I want to teach, but ideally I can just play first,” she says. “I want to be in a band or lead a band… But one thing I do know: I want to be a musician for the rest of my life.”◊