On April 21, 1999, Jarvis Joyce found God while running.

The day started just like any other day for the then-17-year-old Joyce, who lived in Matteson, Illinois. His alarm clock blared at 6 a.m. and he got dressed for school, grabbed his books and caught the bus to Rich South High School.

Joyce got there an hour and a half before the first bell, just as the first faculty members started trickling in. He sat at a table to finish homework, then hustled to his first period class, settling in his same usual seat. At the end of the school day, the last bell rang and Joyce hopped on the bus back home.

Usually, he’d spend hours talking on the phone with friends when he was supposed to be doing schoolwork. But this day was different. An argument with his brother, Carnold, sent Joyce running outside.

He darted to the top of his cul-de-sac, taking a sharp left to follow the winding road. Somewhere between the Odyssey Golf Club and the Vollmer Grove Forest Preserve, Joyce found God. Or God found Joyce, he says.

Many people who find religion usually do so in a more formal way – attending bible study, meeting someone who passes on their faith or going on a retreat or to a new church. For Joyce, it was different. It came from his core, a feeling that he needed to spread positivity to as many lives as he could touch.

He remembers the instant where he decided he wasn’t going to fall back. “I set my heart to that even if the whole world was cynical I’m not going to be that way, and that’s a choice for me that wasn’t gradual. I was running at the time and I was like: ‘If I’m thinking this clearly right now, I don’t want to slip back into it,’” Joyce recalls.

Joyce, at 33, has seen a lot in his time. And his faith has seen him through a number of things. From training in Kenya with some of the top runners in the world to recovering from getting hit by a car in an accident that threatened his Olympic dreams, Joyce says above all that running is his time to think, to pray.

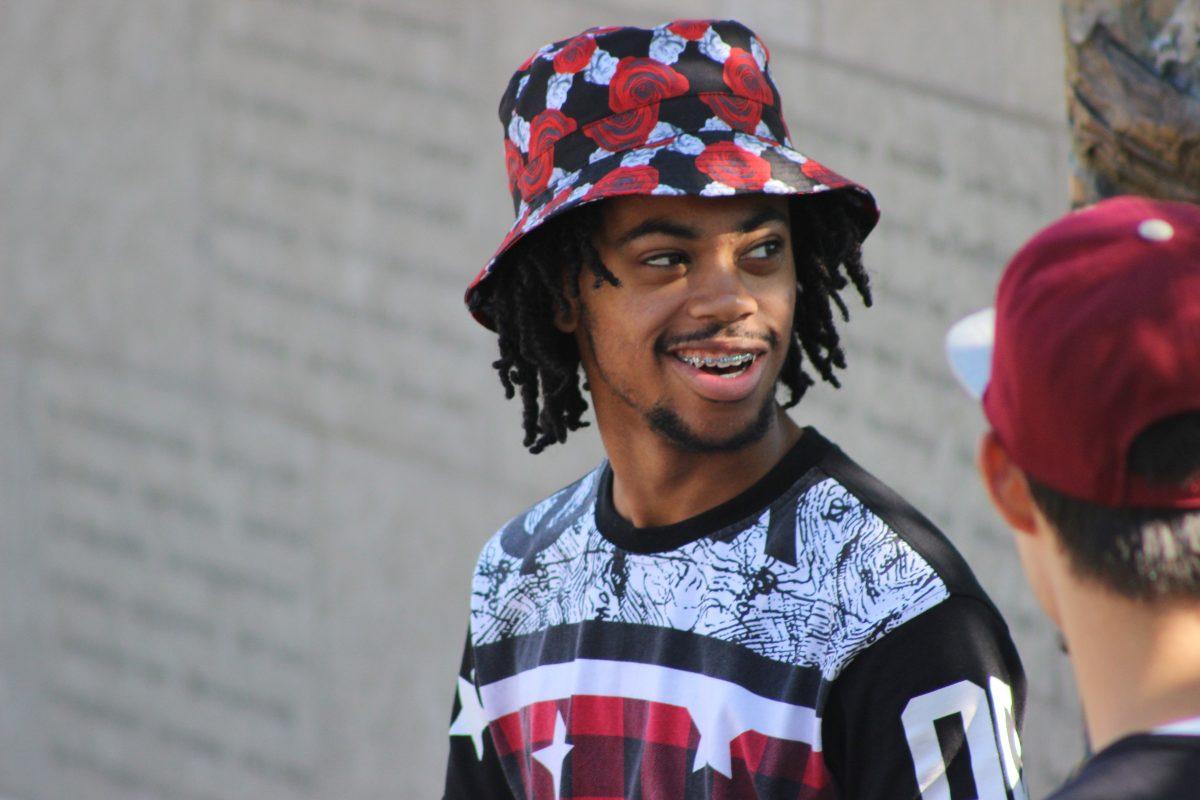

Now, as a new assistant coach for the Grant cross country team, Joyce is gaining attention in the Grant community.

“He demonstrates that anyone can beat the odds, really, as long as they work hard,” says Jack Casey, a junior on the cross country team.

Head cross country coach Doug Winn agrees. “It’s good to be learning from someone that you know is at this elite position,” Winn says. “But even if he didn’t, even if he was slow as molasses, (the cross country runners) would still love him. He’s just that kind of guy.”

The youngest of two boys, Joyce was born March 21, 1982, in Tacoma, Wash. His mother, Carleen Penn, is native to the British Virgin Islands and came to the United States in her late-20s with Joyce’s father, though he didn’t stick around much longer after his second son’s birth. “No one ever talked about him growing up,” Joyce says.

By age 4, Joyce’s mother had moved him and his older brother to Matteson, a small predominantly African-American town outside of Chicago. Growing up, Joyce’s passion wasn’t athletics but technology. When his mother bought an IBM Tandy 1000 computer from Sears, Joyce got hooked. He spent a lot of time in his room, coding and programming, disassembling and reassembling the machine.

“I had taken the computer apart and it was in pieces on the ground,” he recalls. Then his mother came home. “She opens the door, she looks at me, and I’m on the ground with everything…She didn’t say a word. She had an expression on her face that said, ‘I know he’ll put it back together.’”

Though Joyce called Matteson home, the British Virgin Island culture was rich in his house. The family would often spend vacations abroad visiting family. He remembers having a piece of the culture close to him after an aunt moved in around the block. Her presence, in way, started his running career.

“She’d make this amazing coconut bread,” he remembers. “So I’d run to the top of the cul-de-sac. I’d dart there, get the bread in aluminum foil and bring it back like it was gold. So technically I ran, but it was for bread.”

At home, Joyce explored the world through books. He says one of the greatest presents he received was an encyclopedia set for his eighth birthday. This love of learning and knowledge both satisfied his curiosities and checked his reality.

“There were so many questions that I had about life…‘This is going on in the world and we’re being really calm about it?’” he recalls thinking. “Homelessness. The Holocaust. Human trafficking. Drugs, in particular. I was nearby Chicago and there were people who would try and recruit you to gangs and that sort of thing. So you know just questions about…ultimately, how does it stop and what’s going on with the world?”

He says it wasn’t just an argument with his brother that set Joyce running that April afternoon. It was also bottled up confusion for a kid who was thinking about the fate of humanity. He knew he couldn’t solve the world’s problems. But he wanted to make a difference, one positive interaction, one smile, one compliment at a time.

“Jarvis was and continues to be a focused, respectful, inquisitive, studious and intelligent person,” his mother says. “He has always been a very mature individual.”

And then running entered into the picture more solidly. At 17, he opted not to join his high school’s cross country team, but rather participate in the Chicago Marathon. Running, he recalls, “was just sort of like, ‘Even if I don’t get this, it’s not a negative. We’ll see what happens.’”

His mom wasn’t keen on long-distance running. He ran a handful of road races and she had to sign the forms because he was still a minor. “She saw the map of the marathon that goes throughout the entire city and she was like, ‘Are you serious?’” he remembers. “But she knew I wasn’t going to be reckless.”

Joyce studied endlessly, researching successful marathon runners and their careers. He paid close attention to their workout regimens and the conditions they trained in. “Jarvis pretty much trained himself,” Penn says of her son.

Joyce ran the marathon in four hours and 46 minutes. He remembers the first nine miles being breezy until the reality of 17 more set in and his pace slowed. All in all, the race served as a successful jumping off point for Joyce’s future as a runner.

When he graduated from Rich South in 2000, Joyce headed to Azusa Pacific University in Southern California and studied linguistics, with a focus on computational linguistics, a field that he’d always been drawn to.

While there, he met Iraise Garcia. The two became fast friends, bonding over their strong Christian faith and running.

Garcia remembers celebrating Joyce’s 21st birthday with a long run – a mile for each year. “He said, ‘I’ll be running the 21 miles and people are going to be joining me throughout,’” Garcia remembers. “I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re crazy.’ That was one of the things I admired about him so much because he loved to run. I mean, he loved to run.”

Joyce decided to take off the first semester of his sophomore year to travel the country with his guitar, playing in various coffee shops and other small venues. He grew up with a piano in the house and always had wanted to play guitar. At the time, he played with friends. “I wanted to take that semester to really improve,” he says. “We would…just jam.”

When he returned to Azusa Pacific, he muddled through the semester and eventually dropped out before heading to New Mexico. While there, he founded a tech security firm, YCEEK, Inc. He was able to travel the country, working for various companies to ensure their security and track computer viruses.

Throughout, Joyce continued to run daily. In 2005, a group of his friends organized a trip to East Africa through Empowering Lives International, an aid organization. Joyce traveled with them and spent five weeks in Kenya. He says it was unforgettable because of the runners he met.

“There were some friends I made that were runners and being able to run with them daily, getting up in the morning with them before everyone else got up and we’d run together,” Joyce recalls. “It was seeing all the things that I’d read about and being a part of it.”

When Joyce returned to the United States, it took him some time to adjust. The people he was surrounded by in Kenya were thankful and happy, a striking contrast to people he saw at home.

He moved to Seattle and began training under an intense regimen in preparation for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. He was in the best shape of his life, his marathon time only minutes away from Olympic qualifying times.

On a run through the park, he spotted in the corner of his eye something big and fast coming his way. “My only instinct was to jump and grab my knees,” Joyce remembers before getting hit by a car driven by a young woman. “All I remember was windshield, ground and then the hospital ceiling…all I could think about was whether or not I’d be able to run again.”

The accident set Joyce’s training back years. His right knee was seriously injured and he suffered rib injuries that left him in nine months of physical therapy.

“Reflecting back on it, being hit by a car with nothing else between us, I was just super happy to be alive,” he says. “For me, it was like, ‘OK, this is all fixable. It’s going to take time.’”

He thought about the woman who hit him and how racked with guilt she must be, so adhering to his life approach about always being positive, he reached out to let her know he wasn’t holding a grudge.

“It was a really good conversation. She was at work and she was a little bit startled at first. I said, ‘You know what, you did the right thing. You stopped. You called 9-1-1 for help so even though it was not an ideal situation, you still took that and claimed responsibility. We all make mistakes,’” Joyce remembers. “That was good. It allowed that chapter to close.”

And things started to look up for Joyce.

In 2008, he met his future wife, Monica, whose maiden name was also Joyce. Originally from Minnesota, she had just returned from Italy and was staying in a house with some of Joyce’s friends.

He dropped by the house often, first to check on his friends and also to see Monica.

“We had known each other for a little over a year,” Monica Joyce recalls. “We were just hanging out and then we just started having some conversations and then one thing led to another.”

They dated for about a year and married in 2010.

By 2013, they were expecting their first child, a boy. The Joyces were living in Virginia at the time. A new project brought Jarvis and his very pregnant wife across the country to Portland in August. By late November, they were parents.

Last June, while out on a run, Jarvis Joyce stumbled upon the All-Comer Track Meet where he met Winn.

“That was such an amazing, lucky day,” Winn says. “Out of the blue, I asked if he’d like to work with our team and he immediately said yes. And so the next practice we had, he was there. And he was there every single day.”

The cross country season is winding down as both the boys and girls teams look toward the state meet in November. Joyce is happy to be a part of the team. And the runners are glad to have him.

“He seems to do it for the love of running and he brings that attitude of enjoyment which is nice because sometimes we get caught up in the competition side of the sport,” senior Liam Jemison says. “It’s a good perspective. It’s nice to have him there.”

Looking ahead, Joyce is planning to go to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, but he’s not sure yet whether he’ll be a participant in the marathon or a member of the audience. That depends on how well his training goes next year.

He’s upping the intensity on his daily workouts. He rises at 3:57 a.m. every morning and heads to Grant Park for his first run of the day. He has a routine that is intense and exhausting. The mornings involve a 40-minute run, while the evenings are more regimented with either an intense, continuous speed workout or a 90-minute run. On next year’s docket, the Chicago Marathon, the same one he ran 16 years ago as a senior in high school.

After training, he heads downtown to work at his newest technological venture, PeopleBeforeCode LLC, a company he started in 2009 that focuses on research and various projects in the technological field. After work, he attends practice before heading home to spend time with his family and put his son, Jac, to sleep every night. For Joyce, it’s become one of his favorite traditions.

“Sometimes he goes to sleep in 10 minutes…and other times he can be up for a couple hours,” Joyce says. “Sometimes he’s making sounds…and I’m thinking about different things or I’m telling him stories.”

This January, the Joyces are expecting their second child. Jarvis Joyce says he’ll be taking a backseat during the track season because of the new child but he certainly won’t be a stranger to the Grant track team.

As for what’s next, Joyce is excited for future seasons, for Olympic training, for a new baby and whatever else comes his way.

“Everything’s been totally good,” he says. “I’m excited for what’s ahead. It’s important to appreciate what’s right in front of your face, but then also have that hope for what’s ahead.” ◊