PENDLETON — Rosey Sams ducks under the teepee’s painted canvas flap, the light from the sun gushes in and dissolves into a yellow haze.

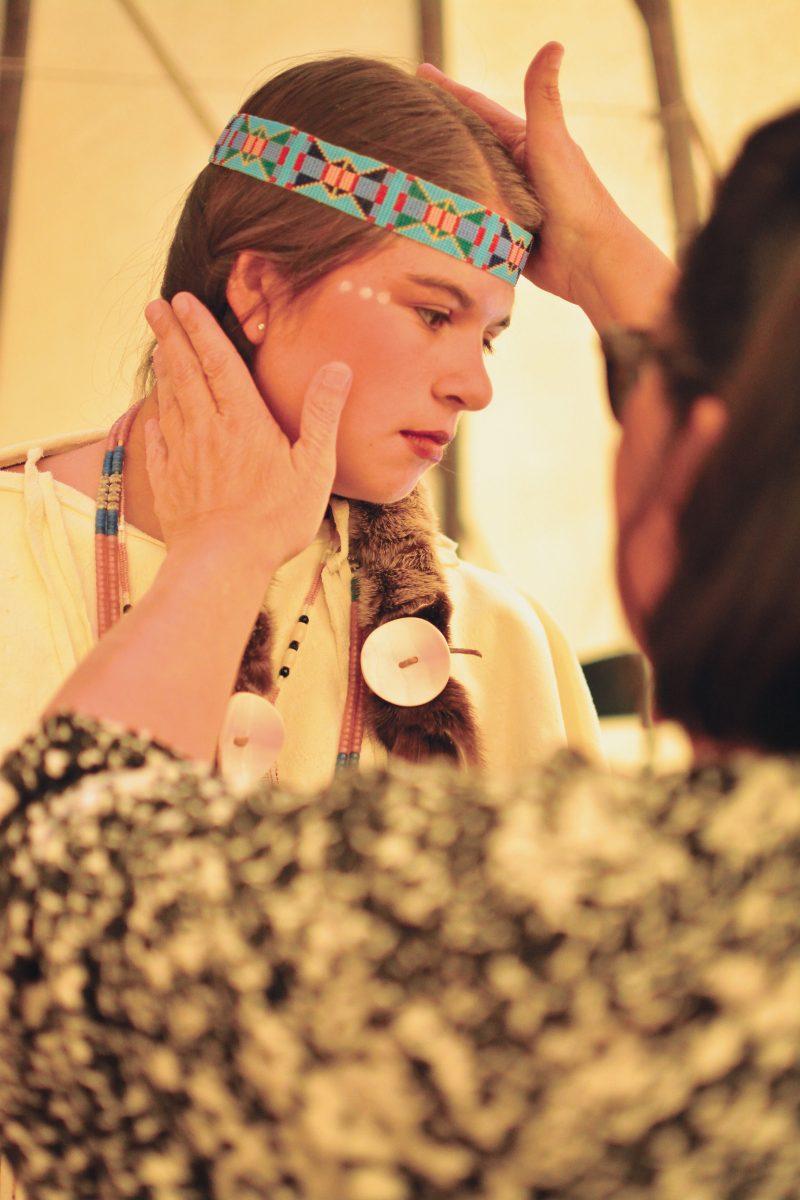

There are three other people with her – a young girl with dark braids, glasses and a cowboy hat; another girl whose round face and two thick braids mirror Sams’; and an older woman stands nearby. “Rose, let’s do the makeup first, before we do anything,” says Sally Kosey, Sams’ great aunt.

She rummages through a large bag and motions for Sams, a Grant High School sophomore, to come forward. Every September for as long as she can remember, Sams has made the three-hour drive up to Pendleton to visit family and participate in the festivities at the Pendleton Round-Up, a weeklong rodeo event that attracts as many as 60,000 people.

“I like to get them ready myself, and then tell them about the stuff that they’re wearing; where it came from, whose family it was in,” says Kosey. “It’s an opportunity to learn and be with their own people.”

Born to a Caucasian mother and a Native American father, Sams, 15, is a registered member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Though she’s grown up in Portland, her parents have worked hard to create equal exposure to both of their backgrounds.

And Sams doesn’t consider herself to be divided between the two cultures. She cherishes both sides of her upbringing. “Maybe to people looking at it, it may seem like I live in two different worlds,” Sams says. “But to me, it’s just me. Its just part of my life.”

Rosey’s father Chuck Sams is the communications director for the Confederated Tribes. He says he respects his daughter for developing her own journey to consciousness. He also recognizes the complexity of the situation.

He points out that growing up in a middle class family, where money and educational resources are seldom issues, Sams and her siblings haven’t had to utilize some of the minimal services provided for Native students and families throughout the Portland area.

Many don’t share this privilege. Portland is home to the ninth largest urban Indian population in the country. Yet, Native students account for the lowest high school graduation rate in Portland Public Schools.

Experts say many families struggle to access resources, and some Native students find themselves caught in an ever-evolving identity limbo with few culturally relevant outlets to guide them through the educational process.

“I think that, you know, it can be really isolating,” says Melissa Bennett, the program coordinator for Portland State University’s Native American Student Community Center. “A lot of people come here because they’re…trying to find ways to connect to indigenous communities and other people who are going through the same kind of thing.”

Rosey Sams says she has not yet experienced the same sort of struggle when it comes to identity. As a sophomore, her priorities are largely focused on doing well in school and showing up for her games with the Grant girl’s soccer team, and hanging out with friends and family.

But the importance of maintaining a connection to her heritage is not lost on Sams. A value that’s been instilled in her since birth, many of Sams’ family members hope that it will remain a guiding force throughout her life.

“I think just wanting to be a part of your culture and wanting to continue to maintain that connection with your traditions is huge,” says Cor Sams, Rosey’s aunt who lives on the reservation. “Because if you don’t, then you don’t. Then you just live in Portland and you come here to visit.

“And we’ve been very supportive in having them have both of that…But you have to know where you’re from, in order to go where you’re going.”

Back in the teepee, Rosey Sams gets up from kneeling in front of her great aunt and begins to shed her everyday clothing. She carefully dons her family’s traditional regalia: a cream-colored buckskin dress; a 100-year-old cornhusk bag; and a beaded pair of lace-up leg warmers.

Eighteen hours earlier, she was busy holding down the fort as the Grant women’s varsity soccer goalie in a Thursday night game. Now, she’s missing school for the day, but it’s important. “It’s about tradition,” her great aunt Kosey says.

• • •

Rosey Sams was born in Portland on Nov. 6, 1999. For the first two years of her life – while her mother, Markelle, worked full time as a special education teacher and her father as executive director for the Earth Conservation Corps, Sams was taken care of by her aunt Cor, who moved to Portland from Pendleton to live in the Sams’ basement.

Cor Sams remembers her niece’s distinct personality – she was always on the move. “You knew that she was doing something when she was quiet…if you didn’t hear Rosey talking,” Cor remembers, “’cause she always had something to say.”

Chuck and Markelle Sams had two other children two years apart – Chauncey and Clara. Chuck Sams knew that finding ways to expose his kids to Native traditions while living in the city was going to be key to fostering their strong sense of community.

Before any of them could walk, Rosey and her siblings would be placed in handcrafted cradleboards and whisked off with family members to different tribal dances and ceremonies, both in Portland and on the reservation.

“We were fortunate,” Markelle Sams says. “Both of our extended families were really open and inviting into both cultures…so you know I think that Rosey just got the benefit of seeing…a wide group of people who appreciated everything about each other; differences and similarities.”

Still, Chuck Sams knew that attending sporadic cultural social gatherings wouldn’t be enough of the foundation in Native education he longed to give his kids.

He wanted to create an avenue for young native students in Portland to learn in a traditional setting, and because nothing of it’s kind existed in Portland at the time, he decided to push for the founding of the city’s first Native Montessori School.

“The ideals and principles of the Montessori school…had the same ideals and values and education as you would on an Indian reservation,” Chuck Sams says. “You learn through interaction…in a group setting that is not competitive in nature.”

The school started out in a classroom at daVinci Arts Middle School with fewer than 20 students. Rosey Sams vividly remembers her time in the program. The students were taught dancing, drumming, storytelling and singing. They learned to be independent, to self regulate and to listen.

Karen Kitchen, the program director for Indian Education Services in the Portland Public School district, has known Sams since she was a baby, and saw firsthand the program’s influence.

“It was a strong academic start, but it was also culturally rich – culturally welcoming,” Kitchen says. “I think the more that we can do as a school district or as a classroom to recognize culture as a strength and nurture that, then more Native students will feel like they’re welcomed, and they can be who they are.”

Just before Sams entered first grade, her parents decided to divorce. “I just remember the day that they told us,” says Sams. “…We had eggs for breakfast or something. And then they were both crying at the table – then they took us to the living room. I didn’t even know what it meant really.”

Though they no longer lived in the same house, Sams’ parents made an effort to uphold a balance for their kids. Their shared familial and cultural values didn’t change. “We’ve tried to set the best example,” says Chuck Sams. “We always explained to the kids that you come from two different cultural values but many of those values align themselves equally.”

From first grade on, Sams remembers her childhood as a frenzy of sports. “I get very bored,” Sams says. “I have to be constantly doing something. I can’t just sit.”

She played basketball and softball, but fell in love with soccer the minute she donned her first jersey.

The transition from the Montessori school to Hollyrood Elementary was seamless for Sams; she enjoyed school and never settled for anything less than her best performance.

But it didn’t take long for the westernized educational system to show its lack of respect for indigenous communities. “There’s not this full understanding of Native American history – particularly in Oregon – and so it’s not taught very well in the public school system,” says Chuck Sams. “I noticed that very early on when Rosey, Chauncey and Clara all went through the fourth grade Oregon Trail Project.”

In a culminating class performance, Sams was cast to play one of the Oregon Indians and intuitively wanted to wear one of her traditional wing dresses for the role. But when Sams brought other dresses to lend her white classmates who were also portraying indigenous roles, they were reluctant.

They wanted to wear their Pocahontas Halloween costumes, instead.

Chuck Sams was incensed. “I had to go up there and tell them that, you know, that’s never appropriate,” he recalls. “If you’re gonna teach history, and you actually have living descendants…then use the appropriate clothing for the time period.”

Rosey Sams doesn’t look back on the experience in a negative light. That comes, in part, because of the confidence her parents have instilled in their three children.

Markelle Sams says of her daughter’s love of education: “She’s always pushing herself. It’s not necessarily common in high school and it’s probably not encouraged in our school system…she likes to learn for the sake of learning and understanding what she’s doing rather than to just get the grades. I see that serving her well in her future.”

Chuck Sams agrees. “I think that education is not something that’s scary to them,” he says. “And so they’ve embraced education, they’ve embraced different subject matters; they have a self confidence in their ability to ask questions when necessary, and know when to be quiet and listen.”

• • •

Many Native families and their students say the disconnect between the dominant culture and indigenous communities is nothing new. Slights like the Oregon Trail Project happen on a daily basis.

Anna Allen, a former youth advocate for Portland’s Native American Youth and Family Center and a member of the Shoshone-Bannock tribe in Southeast Idaho, remembers her own realization of this.

“When you actually look through the history books, they depict native people in a way that is just flat-out not true,” says Allen, who now works as a policy advisor for Multnomah County Chair Deborah Kafoury. “And it’s that typical ‘war paint, in regalia, on a horse, living on the plains in a tepee’…where now that’s just not the case.”

Allen worries about how young students handle this kind of pressure if they haven’t established a sense of community. “We’re caught in this…internal struggle between how do you honor what you’re being told from your elders, in terms of what to prioritize in life, but you also are living as an urban Indian and you’re trying to find a sense of success for yourself,” says Allen. “It’s really difficult to find that balance.”

This concept was modeled for Rosey Sams and her siblings in 2010 when their father moved back to Pendleton to live on the reservation and work in public information and legislative affairs for the tribe.

“I always knew I was coming home at some point and would have to be a part of tribal government,” says Chuck Sams, whose career has spanned working as a naval intelligence specialist and fighting in the first Gulf War to helping set up the first AmeriCorps program in New York City from 1993 to 1995.

It was a tough adjustment for Rosey Sams. “At first I thought, ‘Oh it’ll be kinda cool that he’s living in Pendleton,’ ‘cause we always went there all the time,” she says. “So I liked it there. But then, when he actually moved it was weird. He would just expect us to drop everything here and go to his house for the weekend. Sometimes I’d have sports, and I’d be like, ‘Well no, I have an important game, I can’t just come.’ So he’s more understanding now but at first it was harder.”

Still, the move opened doors for the children.

“Markelle and I came to a decision before we divorced that when the kids turned 12 that they could make the decision where they wanted to live,” says Chuck Sams.

While Rosey Sams and her sister were both content with their lives in Portland, Chauncey Sams was drawn to Pendleton and moved there in 2014. He wanted more opportunities to hunt and fish, and have the chance to connect deeper with his Native roots.

“I wanted to see this side of my family more,” says Chauncey, now 14. “Since it’s so much smaller, it feels you’re in a community instead of like the whole town. When you go to the grocery store, you’re bound to see someone you know, or a family member or something…you feel more connected with everybody.”

Though he’s been living in Pendleton for just over a year, Chauncey Sams says he already feels the impact that living constantly immersed in Native culture has had on his own consciousness.

“Our tribe is kinda getting smaller, and getting diminished,” he says, “and…the people not necessarily connected with the tribe – like Rosey and Clara and how I used to be – we didn’t get to experience that side of it as much. And so now that I have, it makes me like want…the next generation…to be able to experience our culture and heritage as well.”

After Chauncey’s move, life gradually returned to normal in Portland. In fall 2014, Rosey Sams began her first year of high school at Grant. Immediately, her drive and high self-set standards made her stand out to staff and faculty.

“As a freshman, she was very confident,” says Sams’ English teacher, Mary Rodeback. “I wouldn’t say she was competitive in the classroom, but the fact that she is a competitor gives her a poise and a balance to be ready to throw herself into anything…Any question I asked, her hand was up.”

She also made her presence known on the soccer field as the only freshman to make varsity. “Everyone else made a big deal of it,” says Sams. “I was just like happy that I made the team.”

Scott Perkins, Grant’s goalkeeper coach, says Sams’ humility and work ethic quickly earned her the respect of her older teammates. “If something isn’t working for her, she’s ready to tinker with what she can do better,” Perkins says. “I think players look up to her as a goalkeeper and she is mature beyond her age.”

Sams, for her part, takes the responsibility for the team’s success on her shoulders. “I feel like I have more control when I’m back there,” says Sams, who is in her second year as starter. “Because I’m the last line of defense…if they score, it’s on me. So I just get in the mindset of ‘They’re not gonna score.’”

She’s always excelled in the classroom, as well. But her mother discovered a college preparatory program for minority students last year while browsing a newsletter sent out by the Title VII Indian Education Act Project. The program is called Math and Science for Minority Students and is taught at a prep school in Andover, Mass.

It’s geared toward helping students of color pursue careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Markelle Sams showed the newsletter to her daughter and Sams immediately begged to apply.

Of more than 500 applicants, only 39 get accepted to participate in the three-summers-long program. Sams got in. And she had the time of her life. She learned enough chemistry and pre-calculus to make her eyes water, but what stuck out most were the relationships she forged. “We were only there for five weeks,” she says. “It felt like a year, for how much I know those people.”

While Sams enjoyed learning about the varying customs of tribes other than her own, she focused on finding things in common with people from all different backgrounds. The transition back to Portland was rough for her. Her friends were eager to hear about her experiences, but she had a hard time conveying everything the camp meant to her.

Zoe Shaw, one of Sams’ best friends and also a sophomore at Grant, recognizes this as a regular struggle for Sams.

“She does keep that other part of her life more private from other people,” Shaw says, talking about her trips to Pendleton. “Just because it’s hard to explain and you know, it’s a lot to describe…Balancing everything as much as she does…I think there are plenty of times where she would much rather just go to bed or take a day off. But she comes to school everyday with a smile on her face.”

As sports and school both pick up the pace and college looms on the horizon, Sams is doing her best to make time for everything.

“I think it’s diminishing partly, as I get older,” says Sams of her time to touch base in Pendleton. “…It’s harder, like living here and having that side of my family and all that stuff be so far away.”

Sams’ brother openly worries that her distance might inhibit her ability to adhere to a culture that he says flows directly through word-of-mouth, everyday communication. “I just think it’s hard for them to experience as much and respect it as much given that they only get to come up every so often,” Chauncey says of his two sisters. “It kind of worries me that their children won’t be able to…know much about their culture.”

Chuck Sams, though, says he’s not worried. He knows that his daughter has to walk her own path.

“I think every young person is searching for who they are in high school and in college,” he says. “And making their way in the world and self-identifying based on their family experience, what their values are going to be…and what standards they wish to follow. And it can be difficult for a multicultural young person, in trying to figure that out.

“I’m very proud of Rosey and I’m proud of the fact that she has a strong love for both sides of her family, and that she hasn’t had to choose either side…She just is herself — she’s her own person.”

• • •

The sun outside temporarily blinds the three girls as they crawl out from inside the large teepee. Rosey Sams is barely out for two minutes before people start calling her name.

She sees a crowd of friends and family members wandering her way, and walks to meet them. She hasn’t seen some in months.

As Sams takes a moment to catch up, a white woman in a cowboy hat and boots parks her baby stroller and whips out a camera. She asks to take a picture of Sams and her sister, fully decked out in their Native regalia. They oblige without hesitation. It happens all the time, they say.

A few minutes later, Sams and her siblings join the large crowd near the arena’s side entrance. It’s swelling with family members, old and young, who are rushing around, fixing smudged makeup and straightening stray hairs before heading out into the Roundup arena to dance.

Cheers and hoots roll through the stands in anticipation of the “Indian Show.” The cultural disconnect that Allen described was more than evident.

“There’s two sides of it,” says Cor Sams, gesturing to the surrounding scene. “There’s a sense of pride that we have been participating in the Roundup for over a hundred years, and then there’s the 2015 side of it, that you know, we’re not an equal partnership in the Pendleton Roundup.

“They still continue to call us, ‘Oh, the Indian Village.’ If you look around, we’re the only ones caged in.”

Cor Sams motions to the enclosed ring of chain link fencing that contains more than 300 teepees. “So you know there’s always that side to it,” she says. “But I think it’s part of the culture, and that carrying on outweighs some of the bad things that you think about Roundup.”

Later that evening, back in the living room of his home on the reservation, Chuck Sams elaborates on his sister’s observation. “We find it odd, because they’re inviting us into our own home,” he says of the Roundup’s directors. “This was ours first. Pendleton is actually our original village site…And we welcome them into our territory, and we’re glad that they’re here. But you know, they only pass through for a brief five days and then move on. We’ve been here since time began, and we’ll be here whenever time ends.”

He thinks about the world he’s tried to create for his kids. He hopes they will pass it on to their own. “This is home,” he says. “And I’ve tried to instill that in all of my children. That they are members of this tribe, and this will always be home for them. No matter where they go in the world, no matter what they do, they can always come home.” ◊