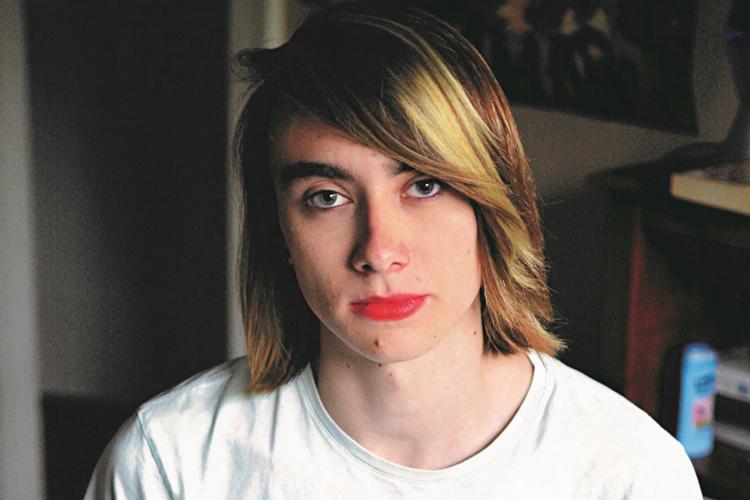

It’s late July and Mona Schraer stands absolutely still, her eyes darting around the Yellow Room of the White House. As she and 99 other teachers from around the country wait quietly, an aide to President Barack Obama warns that the nation’s chief executive will arrive soon.

The doors opens and a smiling President Obama walks into the room, greeting the teachers one by one. Schraer listens to him speak and as he finishes, she steps forward. She feels her stomach drop as the president approaches, reaches out his hand and asks her name.

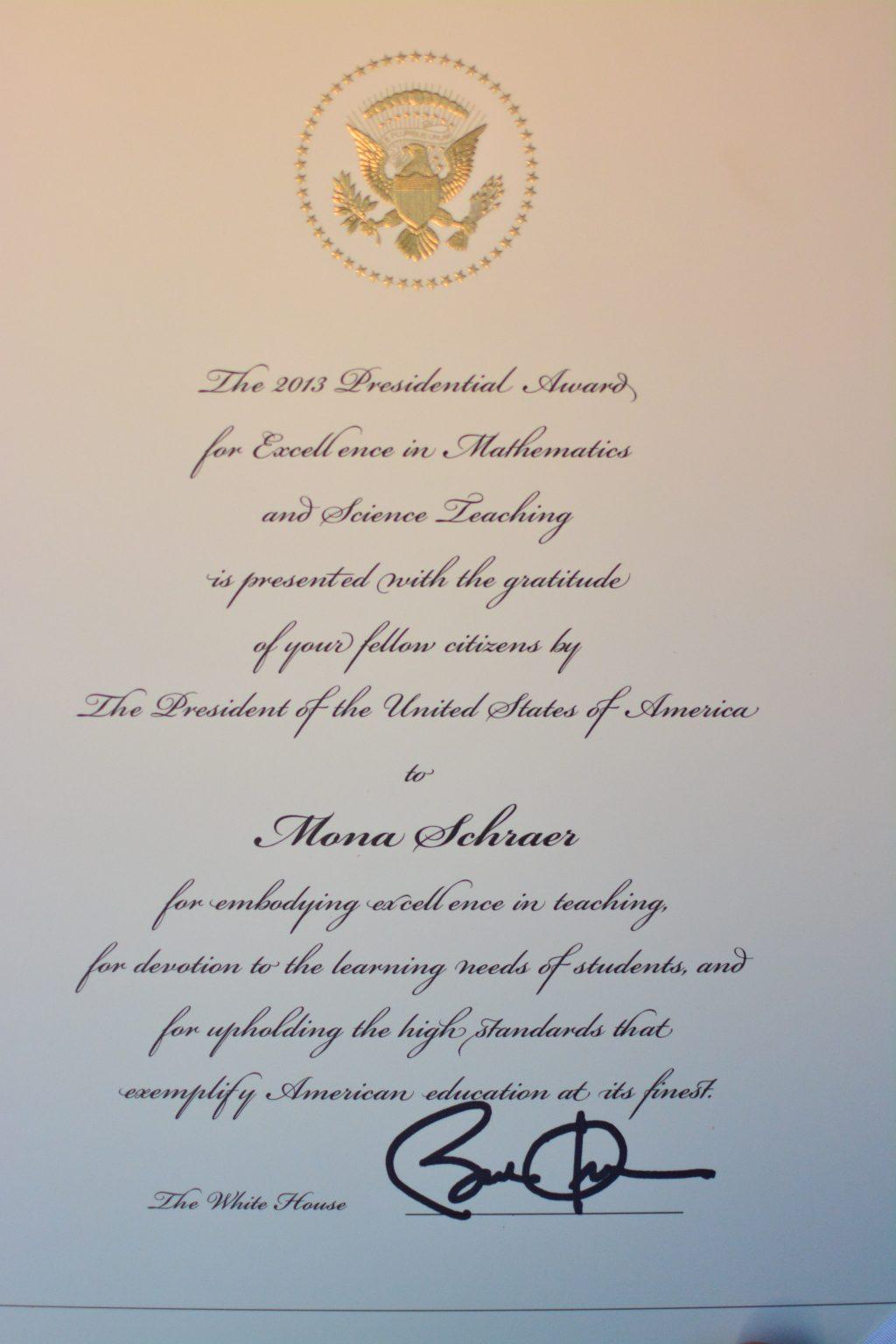

“It’s such a pleasure to meet you, Mona,” he says as he pulls her in closer and congratulates her for winning the National Science Foundation’s Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching. It’s the highest honor in the country that a teacher can get.

“I almost had tears in my eyes,” Schraer recalls.

Schraer has always strived to improve on her approach in the classroom. For her, that means doing the research to understand what works for students and what doesn’t. She received the award, in part, because of the creative ways she’s helped underrepresented populations improve in mathematics.

From working in environmental justice with the National Parks Service to teaching at a low-performing Title I school, Schraer has spent years honing her teaching style.

“In our math department, she is pretty unusual,” says Ethan Medley, a veteran science teacher at Grant. “She has definitely pushed the edges of what a traditional classroom looks like.”

She’s offered underrepresented students paid mentorships to help others who struggle in math, pushed for alternative classes to algebra, and created a new everyday math program to help struggling students perform better in the classroom.

Schraer is hypersensitive about the attention she’s received because of the award. While prestigious (it also comes with a $10,000 check), it means little to her, she says, because she feels other teachers are more commendable.

And in her mind, there are more important things to focus on.

“Even in Grant High School, let alone the state of Oregon, there are so many amazing math teachers that I don’t think I’m more deserving than any of them,” she says. “But it’s the struggle of any award. You have to single out somebody.”

As she enters her fourth year at Grant, Schraer hopes to continue to pave a path for students who are in need. “That’s always something that I’m really interested in on a policy level, on a research level, on a teaching level is…this romantic notion of how do we make the American dream actually a reality for everybody,” she says.

Mona Schraer was born in San Francisco on July 5, 1970. Her twin sister followed minutes behind her. The twins grew up in different co-ops and small apartments around the Berkeley area for the first years of their lives before her parents split up when they were 2.

Schraer’s dad, Arnold, moved to a tiny town in Nevada called Tuscarora with a population of 10. The Gold Rush ghost town quickly became a second home for Schraer.

Her father worked as an artist and led a simple life. He didn’t have much money since he worked as a ceramics teacher but he made enough to cover his $64 in monthly rent.

Tuscarora was quaint, recalls Schraer, who lived there every summer until she was 20. “There was no TV or radio there,” she says now. “There was only one phone line in the whole town.”

The girls found others modes of entertainment. They rode horses with a friend, swam in the nearby swimming hole and helped build her father’s ceramic kilns from scratch.

The little town meant so much to her that Schraer and her family still visit today. “It’s nostalgia. I love it,” she says. “You just go right back into that mode of total relaxation…I like quiet places.”

Back at school in Berkeley, Schraer says she got by as the “good kid that you could pay no attention to and everything would go fine.”

Sometimes, the same went for her life at home where she rarely saw her mother, Karen Kashm. A medical school graduate, her mother kept a busy schedule as a doctor. Schraer remembers bringing fast-food from a nearby joint to the hospital just to eat dinner with her mother.

“I barely saw her,” she recalls. “Not only would she work crazy hours, but she’s on call like three or four nights a week. I would be leaving to my swim team practice at five in the morning and she’d be coming home from the hospital.”

But her mother’s absence didn’t slow her down. In high school, she was part of Peace Club, the Independence for Nicaragua Club and the Overseas Development Club. “I used to cut class but not like cut class to cut class,” she recalls.

“We would all…walk up to UC-Berkeley because at the time apartheid was a really big deal and there were all these sanctions going,” Schraer says of the movement to divest in South Africa because of the practices of its racist government. “So we would protest apartheid and do sit-ins at Berkeley…That’s something I did a lot.”

At the beginning of her senior year, though, Schraer’s life flipped upside down when her father was diagnosed with cancer. “I remember it was severe, pretty fast,” she says. “He went in to get a mole removed… and he said it hurt so much… and then a week later he had a tumor removed from his back.”

He couldn’t afford a caretaker, so Schraer and her sister helped out. Schraer also had friends and people in the neighborhood coming together to help, something, she says, gave his home the feel of a real community. Her father would later go into remission.

Around the same time, Schraer moved out of her mother’s home and went to San Diego to live with an aunt. The aunt, Linda Schraer, says she was thrilled to have her. “It was great because I never had a daughter,” Linda Schraer says. “I’ve always considered her the daughter I never had.”

Schraer didn’t stay in San Diego long. After she graduated, she left to Davis College to get a degree in economics. In her third year, she traveled to Israel as part of an exchange program. But a month after arriving, her father’s cancer came back.

She rushed back to care for him but two months later he died. He was laid to rest in Tuscarora in an old graveyard on the outskirts of town.

“It’s honestly still really hard to talk about. He was only 42,” says Schraer. “He didn’t really sit around and talk about where he wanted to be buried. Sometimes, just dying in itself is so big that you’re not really concerned about what happens afterwards. He wasn’t focused on that. None of us were.”

After Schraer finished college, she followed her career in economics and found a job in Washington D.C. but couldn’t handle her ten hour days in front of a computer. She says her adventurous spirit started to come out and she decided to travel throughout Latin America by herself, a self-exploration of sorts.

Six months later, after her first stint of traveling, she couldn’t go back home. She took off entire summers and months into the year to travel. “When I travel, to me, it’s not even worth it if it’s under a month,” she says.

She spent another six months trekking the globe, landing in Fiji, New Zealand, Bali, Singapore, China and Malaysia.

When she arrived back home, she had the drive but not the money to go back to school. To pay her way through, she hopped into a new job as a teacher with only half a teaching license. California was giving out emergency teaching certificates to willing applicants who had minimal experience because of a drastic shortage in teachers and Schraer got one.

She worked at a middle school in Hunters Point near San Francisco. The school, Luther Burbank, was affected by the illegal drug trade and gang violence. “I just walked in and they gave me a class and I just started teaching,” Schraer says. “It was the first month I think I lost 10 years of my life.

“But then I sat down one day…I read some books…and really thought what do I need to do to make a classroom that really works for these kids?”

Schraer recalls being cursed and yelled at by students and though she felt that her classroom was a haven, she never felt safe in the hallways. She remembers when a fellow teacher had to call 9-1-1 after a gang related fight got out of control.

Schraer left after her first year, but the lessons she learned stuck with her. “These kids touched me so much. How I touched them, I don’t know,” she says. “Coming from where they came from, I don’t know if I could do what they were doing.”

She landed in Oakland Westlake High School, which was also a Title I school. This time, she felt more prepared.

Her passion for the outdoors found it’s way into her teaching when she got a grant to take a group of underprivileged kids on a week-long camping trip. Most of the parents of the students couldn’t speak English, and getting the trip off the ground took a lot of money and work. But she pulled it off.

Schraer says experiences like that are what teaching is all about. “I think it gives more meaning to what you’re teaching when you can see it and touch it,” she says. “A lot of these kids had never been outside of their environment…this was new for them.”

Schraer spent four years teaching in Oakland while she took classes at UC-Berkeley. She eventually graduated with two master’s degrees before weaving her way through a few more teaching jobs. She was also an environmental justice worker at the National Parks Service and she found her husband, Aaron Lewis.

Her roommate at the time set the two up on a date but Schraer wasn’t into it so she cancelled on him. He emailed her the next day and managed to charm her enough to get a second date. “I told him I could meet him at 6 but had something to do at 7,” Schraer recalls. “I ended up staying with him till 8.”

They later married, had a daughter and then moved to Portland in 2008 with another on the way. Schraer started at Grant four years later as a teacher consultant, someone who helped coach other teachers. After her first year, she wanted back in the classroom.

Then-Principal Vivian Orlen hired her full-time. Schraer was exactly the kind of teacher Orlen was looking for. “She really had very strong practices in helping students that think of themselves as not good math students,” Orlen recalls. “Not a lot of teachers like teaching students that struggle and I really needed a strong teacher that could reach that population of students. And I think that was a piece of her passion.”

To reach the lower-level students, Schraer says she started approaching her classroom from more of a research scientist’s perspective than a teacher. “I do a little more research than the average teacher does,” she says. “Does it feel good or do we have data that really shows? If we compare it to another class, is it really better or is it an illusion? I really like data driven decision making.”

Last year, when she led an innovative new program that dualed Algebra 1 with a business class, she took hard data to figure out if it was really the most effective way to teach the class. By comparing it with a regular algebra class, she found great success and is pushing to bring these alternatives to students who might struggle in regular algebra.

Next year, the dual class will be cut but she is leading a new class where students take Algebra 1 everyday. Schraer says this can have a direct impact on the achievement gap. Students of color and people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, who are often the majority in Algebra 1 classes, don’t perform as well and some struggle to graduate.

“It’s not right that these are the kids that aren’t graduating on time,” she says. “We need to really address it in a very real, systematic way to try and find the best solution. That’s something I’m really trying to do.”

When Schraer created a paid math mentorship program two years ago that targeted students of color, she attempted to do just that. “We have this thing where we send some students over to Beverly Cleary to tutor,” Schraer says. “They’re always high income students. Let’s make it more attractive. Let’s have a salary. You interview for the job, now you have a job, we train you…but let’s try and be honest and say, ‘We want students of color to be doing this.’”

The grant to do the paid mentorship lasted for the year but she hasn’t been able to bring it back. Getting grants to pay students is close to impossible, she says.

With so few teachers of color at Grant, Schraer hopes such programs can help change the staff demographics at local high schools. “We need to switch it…and then maybe some of them will fall in love with teaching not because I told them they’d be a great teacher but because they started to work as one,” she says.

Brianna Hayes graduated from Grant last year and is headed to the University of Oregon. She says she got more than just improved statistics skills from her class. “Everything we did in that class was connected to some event in history that you didn’t know about,” Hayes says. “Or some relevant issue that needs to be discussed that isn’t being discussed.”

Hayes remembers when a white Ferguson, Mo., police officer was not indicted for the deadly shooting of a black teen under suspicious circumstances. Hayes, who was president of the Black Student Union, was upset.

“She had stats to prove that African-Americans are more targeted by the police,” says Hayes about Schraer. “She is one of the realest teachers at Grant. You can be honest with her and she’ll be honest with you.”

Schraer says there’s still a lot of work to get done at Grant. She recognizes the hard work and intentions of the staff but says there’s a long way to go when it comes to reaching all students.

“I think people are trying really hard to figure out how to close this achievement gap,” she says. “How effective the things we have done have been I’m not sure. I think we have a really long way to go. I think our hearts are in the right place. But I don’t think we have yet to come up with a formula to solve it.”