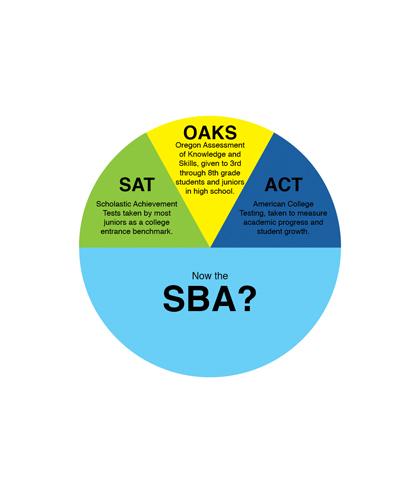

Get ready, students in Grant High School’s Class of 2016 and all those who follow. You officially have another standardized test to tack onto your calendar.

Starting this spring, juniors will have to pass the Smarter Balanced Assessment – a rigorous, two-subject test that lasts nearly nine hours. And you have to pass it to graduate.

Some educators say the SBA will be an effective way of comparing student performance in schools, but others have reservations. Despite years of national tension about the value of standardized testing and its place in education today, the Oregon Board of Education is moving forward.

But whether the tests are ready for students remains up in the air. The practice test a few Grant teachers took had kinks in it. That has led some educators to worry whether it will be any better than its precursors.

Previously, Oregon has used the OAKS test – short for Oregon Assessment of Knowledge and Skills. But administrators felt the hour long, multiple-choice test generated too low of a standard.

“The idea is that the old tests weren’t rigorous enough and that they weren’t really measuring what students knew and could do,” says Grant Vice Principal Kristyn Westphal.

So in 2013, the Oregon Board of Education voted to join the consortium. The first wave of tests will be taken this spring and scored. Results will be counted toward school report card ratings.

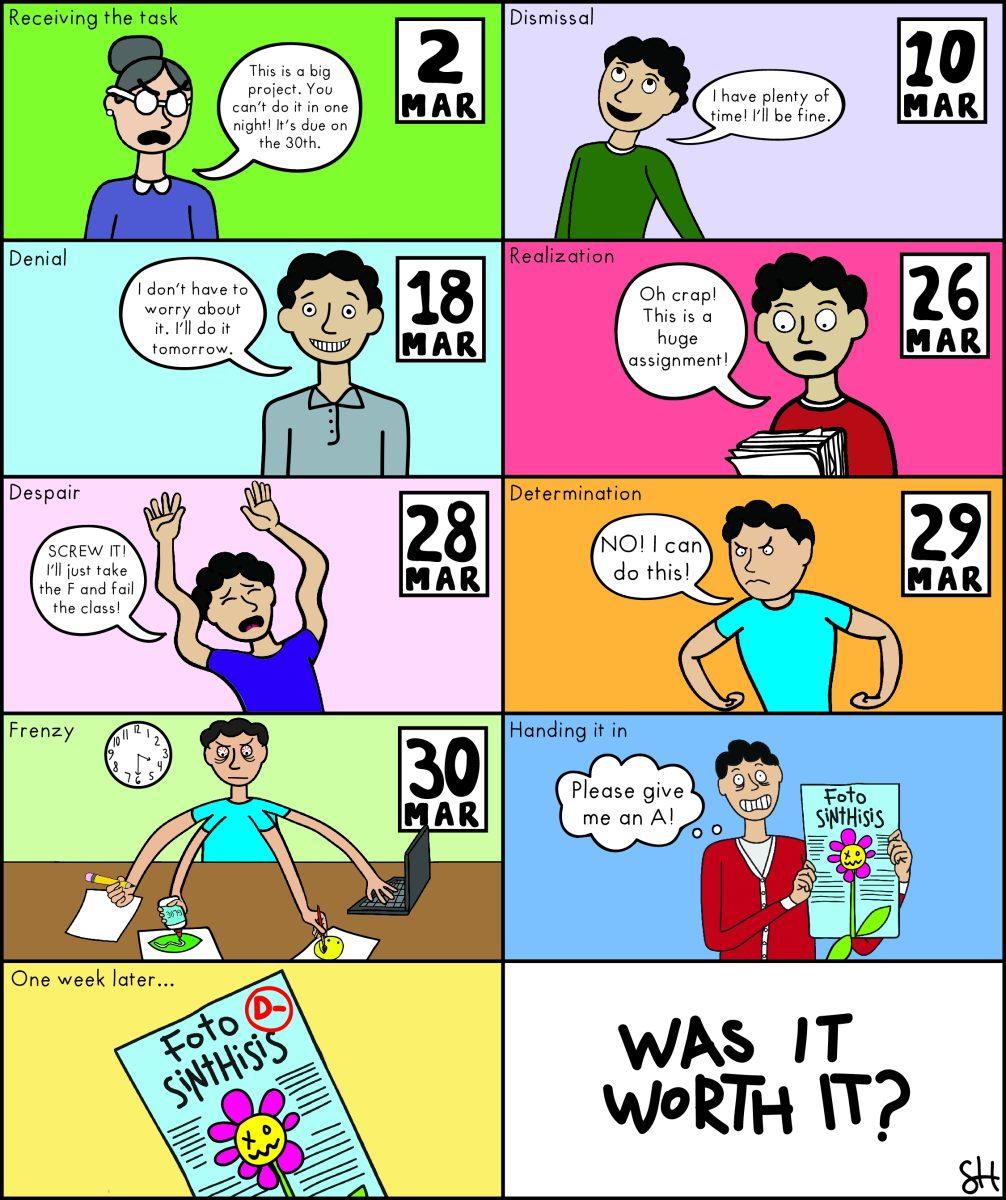

For junior Eliana Meyer, testing never seems to truly express her academic abilities, she says. “Say someone gets tested and they just mess up or they’re nervous or they’re just a bad test taker,” Meyer says. “It does not show or express their knowledge in any way because of the way you’re tested.”

The SBA, which will be split between language arts and math, is supposed to be the solution to Meyer’s worry. Instead of only testing for correct answers, this test will also take into account students’ reasoning and critical thinking by having people, instead of computers, score certain parts of the test.

But many teachers predict low passing rates and have tried to help students fulfill the testing requirements for graduation before they take the new test.

Doug Kosty, the assistant superintendent of assessment and information who is Oregon’s lead for the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium, says the passing score for the test won’t affect graduation rates. The aim, he says, is to correlate SBA scores with OAKS so the requirement stays the same.

Grant English teacher and instructional specialist Therese Cooper says she and other teachers wonder how it will all work out. “We don’t trust that things will go the way the state says they will go. This was especially true last year when we weren’t hearing much from the state,” she says.

Lately, some Grant teachers have taken the SBA practice test to get a feel for what it’s like. Though the test has questions for juniors, teachers found some to be difficult enough to raise eyebrows.

When Grant geometry and algebra teacher Susan Shea took a practice test, she tried to input an answer to an algebra question but the test wouldn’t accept it. After repeatedly trying to write her answer the way she teaches her students, Shea realized she had to write it a different way.

Ultimately, Shea wonders how prepared students will be. “Does this child understand how to get the equation? Yes,” she says of her experience on the practice test. “Do they understand how to write it out correctly? Yes. Did the child get it right on the (SBA)? No.”

Grant math teacher MaLynda Wolfer also struggled with how to interface with the test. “I felt like I couldn’t get the computer to work, even though I knew the answers,” she says.

Algebra teacher and instructional specialist Barbara Riggin believes students could work their way around the issues – but that would take practice. “I don’t think we have enough technology in the building for students to really utilize that and be comfortable with conveying their knowledge in that way,” she says.

Other issues, such as the overall level of difficulty, may be more complicated to solve.

Wolfer was surprised at how hard a question in particular was. “There was a Smarter Balanced problem set we did at the beginning of the school year as teachers that was nearly impossible for us to solve. I was not the only person in the group who was like, ‘I don’t even know where to begin,’” she says.

The question required Wolfer to access information she didn’t teach her students. For Wolfer, that raised concerns. “If I don’t know where to begin, then my students are definitely not going to be in a place where they can begin,” she says.

In the end, Wolfer says that “there’s a make or break attitude about Smarter Balanced that feels inequitable.”

For Cooper, the language needs some work. “They’re testing you on how well you can organize a paragraph, and there are problems with that because it can be very subjective in terms of your decisions you make as a writer,” she says. “They’re trying to objectify something that’s very subjective.”

Portland Public Schools has already come under fire for lack of teaching time in schools and the SBA is not going to be any help, some teachers say. Each section takes two weeks.

“That means you have two weeks of instruction that an English teacher doesn’t get to give ‘cause we’re testing; likewise with math,” says Cooper.

Kosty says the issue is very “complex. We are doing time studies…and we’re analyzing what the results will look like. But until we actually see them, we don’t have any recommendations. We have to take a look at what the data tells us.”

Not only is the loss of valuable instructional time a cause for anxiety, but for many students, the SBA will be the longest test they’ve ever had to take. Some teachers and administrators are worried juniors won’t have the endurance to stay focused for the duration of the test.

“I think some students have the stamina to be successful in longer tests, but I do think for a lot of students they haven’t had practice to do something like that and maybe haven’t developed the skills or self-regulation necessary to sit and focus for that long,” Westphal says. “So I do think it could skew results in what students can really do.”

Some say that given the resistance being seen across the country about the issues around the new test, it might be taken away. Others say educators might try to make improvements.

“They’re testing you on how well you can organize a paragraph, and there are problems with that because it can be very subjective in terms of your decisions you make as a writer.” -Therese Cooper

Meyer can already feel the anxiety stacking up. “We haven’t talked about it really in any of my classes so far, and yeah it’s kind of making me nervous about it,” she says. “It just seems like another unnecessary test that is given to us as an eleventh grader.”

Another junior raises concerns, as well. “I don’t know when I’ll have to take it,” says Collin De Kalb. “I don’t really know how much I should prepare for it. No one has told me anything.” ◊