The first time James Batson heard the roar of the fighter jets, he knew. He was just a boy, an 8-year-old on a field trip to the Oregon Air National Guard Base where he got to listen to then-President George H.W. Bush speak – too young to understand the politics of the time, yet old enough and brave enough to boldly ask the president if he could have a sleepover at the White House.

As a child, Batson had experienced planes, but only from afar, watching with his head turned upward as they floated miles overhead. Now, in May 1990, he was up close, a spectacular fleet of Air Force One fighter jets on display behind the thin yellow rope that separated Batson and his classmates from the 41st President of the United States.

Meeting the president was memorable, of course, but what happened afterward was defining. As the class left the air base and walked back to the school bus, a roar greeted Batson’s ears, a deafening sound that he would never forget.

“As we were leaving, I heard this loud sound,” Batson recalls. “A loud, loud sound. A rumble. I looked up into the sky and saw fighter jets taking off.

“To see them that close up and to hear them that loud…that was something different. And from there, I was hooked. I knew that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to be a pilot.”

Batson, a 1999 Grant High School graduate, is 33 now, a commercial pilot and flight instructor at Hillsboro Aero Academy. What started out as a childhood dream 25 years ago has blossomed into a profession that allows him to see the world from a different point of view.

“When I’m in the air, and I’m at the controls,” he says softly, “I’m at home. That’s where I’m comfortable.”

He’s faced struggle getting to where he is now, but his perseverance has opened doors. He’ll be moving to the East Coast in June to work for Air Wisconsin, a regional airline. He sees it as the next step in his lifelong journey that he hopes will culminate with a position as an international pilot.

“James is one of those guys who always knew what he wanted to do,” says Garon Vasquez, who went to high school with Batson and remains a close friend. “And I think there’s only a handful of guys like this.”

Batson was born in Evanston, Ill., but he moved to Portland as an infant. His childhood days were spent in Northeast Portland, on 14th and Holman, where he would go on to attend Woodlawn Elementary School. Growing up, Batson, or “Juney,” as his mother would call him, was constantly playing outside of the house. His neighborhood was filled with kids his own age, and they took advantage of the opportunities of freedom they had to have fun on their own. They thought of themselves as professional BMX riders, says Batson, and would regularly find local parks or trails to ride on, sometimes even cruising around the St. John’s neighborhood.

Mary Batson, his mom, recalls a time his older sister, Melissa, left her bike on the front porch. She came back outside to find it missing.

“Next thing you know, here comes Juney, flying around the corner, riding that bike so fast he couldn’t steer it!” Mary Batson remembers. “But he managed to turn that corner and crashed it into the grass. I never had to teach him to ride.”

Melissa Batson had a wry sense of humor and often tried getting her brother into trouble. “She had her way with my mom,” he says, laughing. “She would always lie and my mom would believe her. Now, my mom is starting to see. She says, ‘Melissa, why were you always getting him in trouble?’”

In his own time, Batson was a typical kid who cut his own path: a hockey player, a speedskater, a drummer fascinated by the sounds. “I didn’t let color or anything like that limit my choice of opportunity in what I could do,” he says. “I was never afraid to go outside the envelope and just be who I am.”

He participated in activities at Self Enhancement Inc., a social service program that provides opportunities for kids in North and Northeast Portland. “If it wasn’t for SEI, I wouldn’t be in this position that I’m in today,” says Batson now. “They were so helpful in making sure that we had a vision and that we had a dream. And if we had a dream, that we could attain that dream.”

It was on an SEI field trip that Batson met Bush. The president approved the sleepover request but Batson had to settle for a chance to sit in the presidential limousine where he was allowed to talk on a loudspeaker to the crowd. About a week later, he received an autographed photo of the two of them in the mail.

Batson’s parents divorced when he was still in elementary school and he grew up in a single-parent household with his mother and sister.

The elder Batson was in the military, a drill sergeant during the Vietnam War. He retired when Batson was still a child. After the divorce, he moved back to Evanston. “I remember going fishing with my dad a lot as a kid,” he recalls. “Once we got to the outskirts of Portland, he would let me drive. He taught me all that stuff. He got me into baseball, taught me how to pitch. It’s not like he wasn’t around all the time. It’s just that when they split, he moved back.”

Despite the distance, he remained close with his relatives. “I came from a family that was pretty tight,” he says. “My mom’s side of the family was here in Portland, my dad’s side was in Chicago, and no matter what side I’d go to, I always felt like I was part of a good family.”

Batson and his sister didn’t grow up in an affluent household, but that didn’t stop them from doing things.

“(My mom) taught us respect,” he says. “To be responsible. And if you have a dream, don’t give up on your dream. You gotta work for that.”

Mary Batson made sure her children were focused on school. “My mother was very strict,” says Batson. “If I was messing around in school, she would attend class.”

He went on to Harriet Tubman Middle School and his mother sent him to Grant. Most of his friends went to Jefferson and Mary Batson wanted to make sure he kept his focus.

“I get there and I don’t know anybody,” he says. “The teachers, students, staff — everybody there was so nice. They never made you feel like you were an outsider. Always made you feel like family. And I was proud to be a General.”

He played pitcher and center field on the baseball team, his fastball topping out at 87 miles per hour, and also wrestled and played football during his time at Grant.

He was well-liked around school, someone who easily made friends. “He was a jokester,” says Vasquez. “He was always smiling. The thing I remember about James is that he always knew someone. He always knows someone, and people always know who he is.”

Batson also took Japanese in high school, a language that would end up changing his life. “I was fascinated by the writing,” he says now. “I just thought it would be cool to learn.”

During his senior year, Batson received a call from SEI officials. Ed and Sue Cooley, a local couple from he met during middle school who had donated to the organization, wanted to pay for him to attend flight school at their Hillsboro company.

“I remember they asked, ‘Does anyone want to be a pilot?’” says Batson, recalling when he met them. “And my hand was the only hand that was raised. And after I talked to them, I said ‘Hey, can you send me some information in the mail about your facility and the cost? I’m gonna rake leaves, I’m gonna wash cars, I’m going to save money so I can become a pilot. I’m going to do my pilot training at your flight school.’”

Batson remembers that flight school cost around $60,000 to $70,000. The Cooleys set him up for a future as a pilot. “That just…it doesn’t happen,” he says. “And it’s just a blessing.”

He started flight school toward the end of high school. When he graduated from Grant in 1999, he traveled with a friend to Japan and stayed for three months. The friend had been an exchange student from the country and exposed him to the culture there.

Batson learned that his Japanese needed work. “After I graduated, I felt like I was able to communicate, but it was light,” he says. “Those three months in Japan really helped me out. It’s like a giant classroom for you. Only hearing and speaking as much Japanese as I could really helped out. I came back to Portland and said, ‘I really, really want to learn Japanese.’”

After returning to Portland, he found work with American Airlines, working as a ramp service employee to load luggage onto planes and guiding through takeoffs and approaches to the terminal. He enrolled at Portland State University before moving over to Portland Community College where he received an associate’s degree.

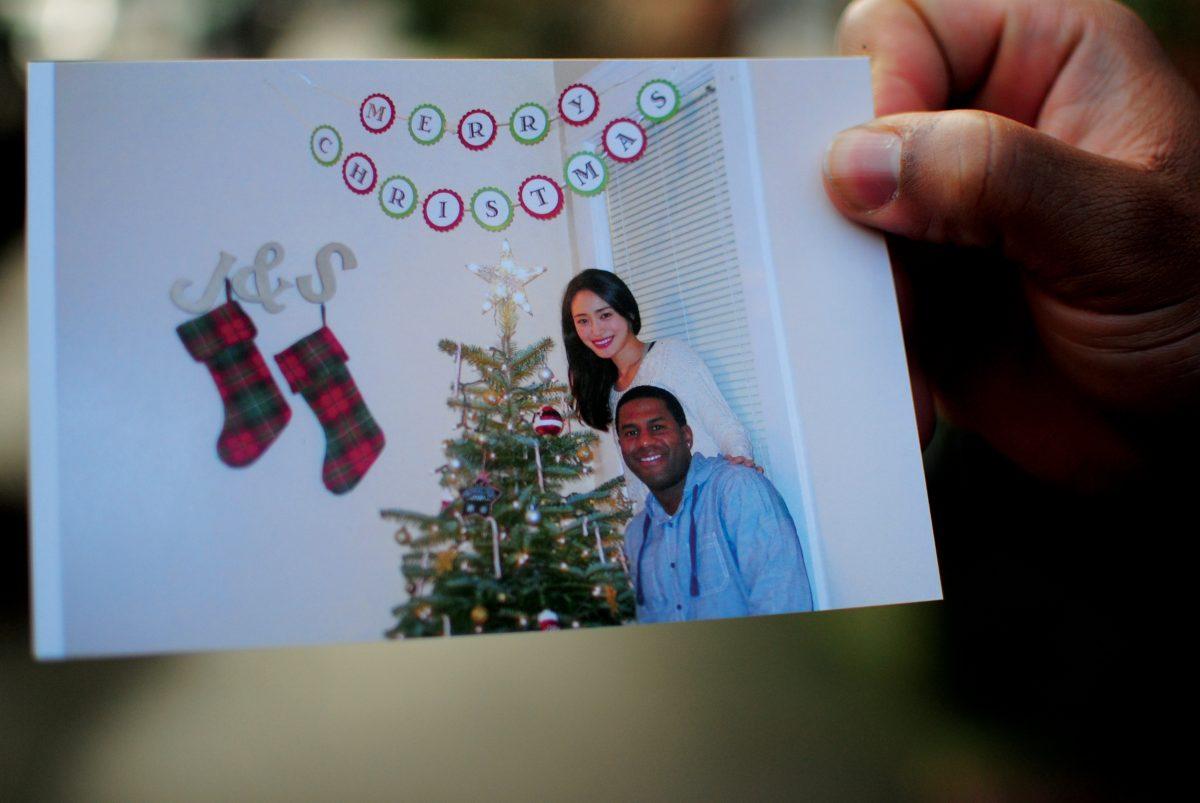

He enrolled at Portland State again and graduated in 2006 as a Japanese major. He met Shoko Suzuki, a Japanese student who was studying at PSU, at “Japan Night.”

“When I saw her, immediately my heart started racing,” he remembers. “My hands got all clammy and sweaty. I introduced myself and I fell in love with her. I didn’t even remember her name after the first three seconds because I was just so nervous.”

She remembers Batson as kind of an odd character.

“He came up to me and asked if I wanted to wear his watch,” she recalls. “My first impression was, ‘This guy is crazy.’”

She returned to Japan and worked as a flight attendant, keeping a long-distance relationship.

Batson worked sporadically at several airlines doing ramp service work and tried to fit in hours toward finishing flight school. He still wanted to be a fighter pilot but his dream remained out of reach.

When he was laid off from his job in 2009, he tried to figure out what to do next. “That’s when I decided, ‘OK, you know what? If I want to become a professional pilot, I have to do something,” he says. “‘I can’t just continue to interview at the airports. I gotta make this happen.’”

He applied for a slot with the Japanese Exchange and Teaching Program, a Japanese government initiative designed to bring native English speakers to Japan to teach. He was accepted and sent to Omiya, a small town north of central Tokyo.

His relationship with Suzuki continued. Then disaster struck. On March 11, 2011, part of Japan was rocked by a 9.0 magnitude earthquake, followed by a tsunami.

“I remember the clock fell off the wall and the glass shattered,” he says. “I’m thinking to myself, ‘Wow, this is not good. This is really, really bad.’ And more glass broke, and I just thought to myself, ‘I can’t believe I’m going to die like this.’

“I remember thinking I was never going to see my parents again, my family, my sister, my nephews. I couldn’t believe I was going to die.”

He survived and returned to Portland briefly before going back to Japan. He and Suzuki got engaged and they stayed in Japan for a few years.

They came back to America for good in August 2013. He was unemployed but in good financial shape after living in Japan. He completed his pilot training and began looking for a position, submitting applications to airlines across the country.

The Federal Aviation Administration, which oversees air travel and commerce, had recently extended the minimum number of training hours necessary to fly for an airline to 1,500 hours. Batson had only 350. It’s fairly uncommon to hire a newly trained commercial pilot with limited hours, but Batson decided to apply to a regional airline anyway.

“I said, ‘You know what? I’m just going to give it a shot. See what happens,’” he says now. “I knew I didn’t have the flight experience, I knew that I wasn’t going to get an offer.”

But a short time later, he got a call from Air Wisconsin, a regional service for US Airways. The company wanted to fly Batson out for an interview.

He flew to Norfolk, Virginia, where he went through a series of tests and interviews. He did well and they extended an offer. He still needed flight hours before getting officially hired. The fastest way to get them? Become a flight instructor.

He went back to the Cooley’s company, now called Hillsboro Aero Academy, to complete flight instructor training and has been there since. Batson and Suzuki got married last November and live in Northwest Portland.

At work, Batson trains a number of Chinese students who learn at the academy before going back to fly for airlines in China. He has to be careful because of the responsibility that comes with being an instructor. If his students make a mistake, it reflects poorly on him.

But the students say they like his focus and devotion.

“He’s a very nice instructor,” says Xue “Lenny” Li, a Chinese student at the academy. “Very patient, very good skill. He’s just like a friend. I remember (my) first flight. I didn’t know James and we just met. I did very bad. He said, ‘Hey, it’s OK. I felt the same thing.’ I feel good when we fly (together).”

Batson puts in long hours at work and also supplements his family’s income by working shifts as a ramp service worker. His wife is waiting to receive her immigration Green Card and can’t work until that happens.

“Every day, I’m always tired,” he says. “The instructing job…I enjoy it. But I wanna fly jets. That’s what I want to do. Some days, I pray for bad weather because I need a break. I do. But it’s called being responsible and making things happen. I know how to work hard. It’s nothing new.”

Batson cleared the 1,000-hour mark in late February and is expected to reach 1,500 by June. Air Wisconsin didn’t set a deadline for him, but he says he’s eager to finish and get to the next level. He anticipates being based on the East Coast, working out of New York or Virginia.

“The goal is to get on with American or United or Delta,” he says. “It’s just about getting more experience, getting your name out there.”

The dream to become a fighter pilot has been put on hold, maybe for good this time. “I could still pursue it, but I don’t really think that’s my lifestyle anymore,” he says. “I’m more about family. Now my mentality kind of shifts from being fighter pilot…to a family man. I’m just trying to make that happen.” ◊