At first glance, Shirley Kanada’s childhood recollections seem normal. She swam in a nearby swimming hole, had frequent visits to her aunt and uncle’s home and played with her neighbors.

But growing up for Kanada was different. The swimming hole was filled with eels and sat isolated in a barren area. The homes in her neighborhood were made up of U.S. Army barracks. If she ever dared look up while playing, she was greeted with the gaze of American soldiers, guns at the ready.

Two blocks away, Joni Kimoto experienced the same mistreatment. For Kanada and Kimoto, who both graduated from Grant in 1956, home was Minidoka, a relocation camp in Hunt, Idaho. That’s where they and nearly 10,000 other Japanese people who resided in America were forced to live during World War II.

At the time of their incarceration, Kanada was 4 and Kimoto 3, both Japanese-American girls who were interned with roughly 120,000 other people of Japanese descent in camps located in isolated areas across the country. The tension that existed between Japan and America during the war would ultimately lead to an experience that dismantled the dreams of Japanese families, leaving many in financial ruin across the country.

“Everything was gone. Your life was gone,” says George Nakata, a Japanese American who was interned during his adolescent years. “It’s untold in textbooks. It’s the story of a people who had their civil rights stripped away. People don’t understand. They say, ‘This happened in Portland? In America? The land of freedom?’ Yes, it did. We lived through it.”

Kanada and Kimoto, both 76, say today that the time they spent in camp has made them stronger.

“Any adversity grows a person,” says Kanada. “So I can take a lot of stuff without falling apart. I was made stronger by it just by the adversity of having so much prejudice against me. That grows you into a stronger person. Some fell apart, but others grew stronger.”

Shirley Kanada was born on May 30, 1938, to Kenjiro and Kimiko Sasaki, who owned a farm in Milwaukee that produced lettuce and celery.

Kimoto was born six months later, on Nov. 19, to Kastumi and Kiyoko Nakayama, who operated a grocery store in Southeast Portland near Franklin High School.

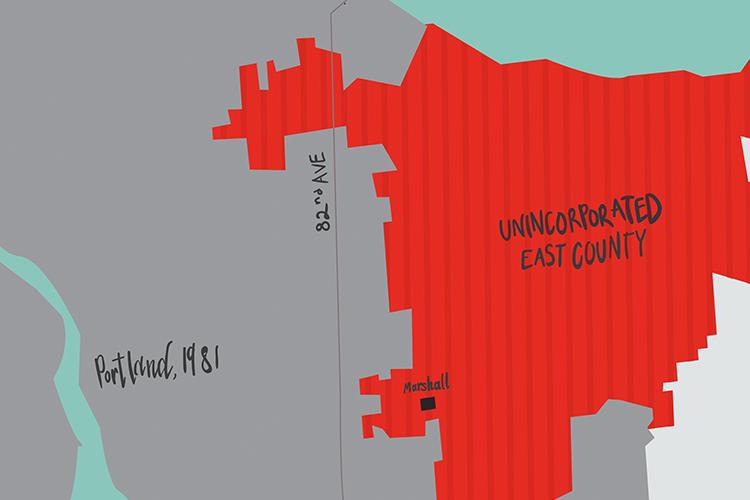

In the 1930s, the Japanese population in Portland was small, but thriving. In locations across Portland and up and down the West Coast, small Japanese communities operated hotels, restaurants and beauty parlors in areas known as “Japantowns.” They were economically diverse regions that were home to thousands of families.

“There was extreme tension between America and Japan,” says Nakata. “The environment in America was hostile toward Asians coming here. It’s kind of human nature to band together with other people like you. Similar language, similar food, similar culture.”

On Dec. 7, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy installation in Hawaii. The attack led the government to declare war on the Empire of Japan and World War II was now fully engaged.

A little more than two months later, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the placement of military zones across the United States and leading to the deportation of Japanese, Italian and German civilians living in America to internment camps.

Many Americans considered the Japanese living on the West Coast to be a threat to the safety of the United States. They were considered spies and were likely to commit espionage, military officials said. It wasn’t uncommon for some Japanese to be referred to as an “enemy alien.”

Two-thirds of the Japanese who were incarcerated were Americans, including Kanada and Kimoto. Even U.S. citizens who were just one-sixteenth Japanese were subject to incarceration. Japantowns across the country were disbanded, left behind by the thousands of inhabitants forced into internment camps.

Authorities apprehended religious leaders, business owners and other prominent members of the community for suspicion of espionage after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

The rest of the Japanese were given two options after Executive Order 9066 went into effect: voluntarily move from the West Coast, or stay and wait to find out what would happen next.

Jean Takashima, a Japanese American who now lives in Southeast Portland, was 9 when she was interned. While her memories of staying at an internment camp are limited, she vividly remembers the weeks prior to their removal.

“We couldn’t go out after 8 p.m.,” she says. “One time my brother had to go out and get bread or something, and my parents told him: ‘If they ask you, tell them you’re Chinese.’”

The curfews were implemented in order to slow down select businesses and eventually grind Japantown to a halt, says Nakata. If business owners who relied on morning deliveries or pickups couldn’t be out in the early hours of the morning, they wouldn’t be able to operate.

Later, the rules tightened. Exclusion orders directed toward the Japanese were sent out, stating that they had anywhere from a few weeks to a few days to report to an assembly center for relocation.

They were forced to sell everything and only allowed to bring what they could carry in a suitcase. Japanese families across the U.S. began to sell precious belongings and prepare for the change.

Kimoto’s parents sold their home and grocery business. A white family friend held onto a few storage trunks of their things. One held a set of Japanese dolls that Kimoto still has today.

Kanada’s family left a truck and a piano in a neighbor’s barn. Everything else, including the family farm, was sold for $500.

“My parents didn’t know what to do with that $500,” says Kanada, “Because who knew? It could have been taken away.”

Her mother took the money and purchased a diamond that she put in a ring. “It was something,” says Kanada, who today wears the ring on her left hand. “They couldn’t take it away.”

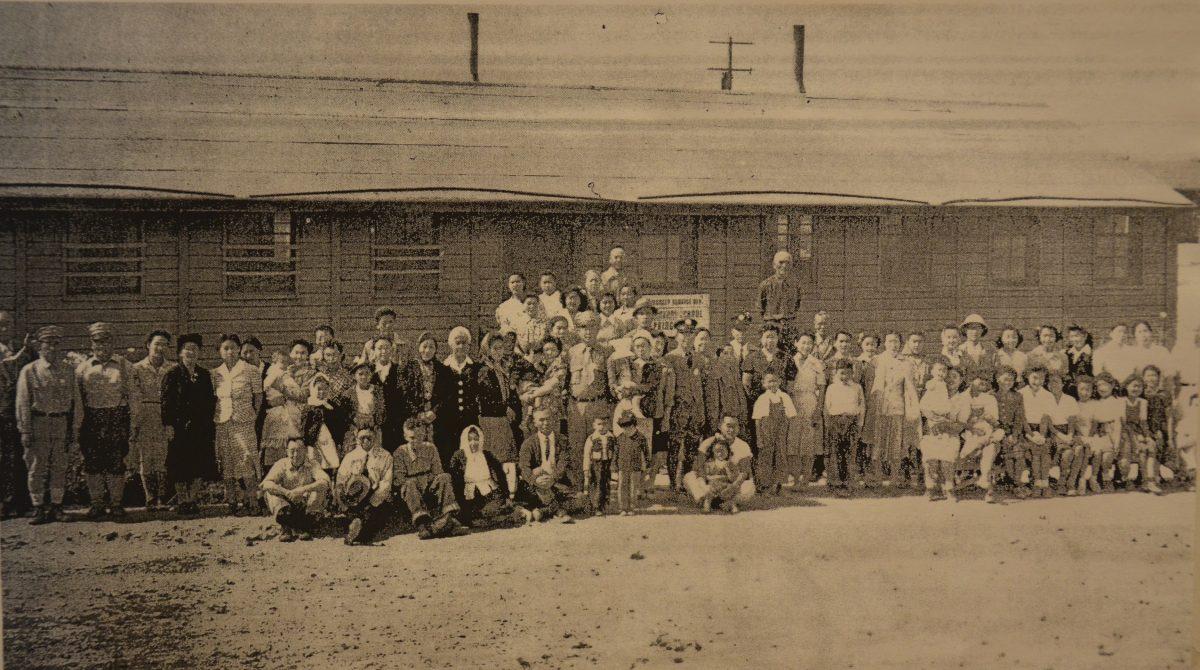

Kimoto and Kanada, along with around 3,500 other Japanese living in the Multnomah County area, reported to the Portland Assembly Center – a livestock yard – in North Portland.

“I still remember the first time that we walked into there,” says Nakata. “It’s still in my mind. The manure’s pungent odor coming through the flooring. Fly paper, black with flies, hung all over. Barbed wire all around. Armed guards marching around. At night, you could hear babies crying, people talking, pigeons flying around.”

Each family crammed into their designated livestock stall, which hadn’t been cleaned prior to their arrival. All they were given were boards to place on top of the manure and mud, and canvas bags to stuff with hay for bedding.

“People say it was a relocation camp,” says Nakata. “I say, ‘Come on, get off of that.’ When you relocate people, it’s because there was a flood or an earthquake, and you put them in a high school gymnasium. That’s relocating people. Not when you strip them of their freedom and take away their rights.”

While in the assembly center, Kanada fell ill. She got the measles, mumps and chickenpox all at the same time.

Some families stayed there for nearly five months, scared, exposed and oblivious to what would happen next. On the weekends, people would often get in their cars and cruise by to see the incarcerated Japanese.

“You tried to make life bearable for yourself, and that’s what we tried to do,” says Nakata. “But it was hard when you were stripped of all your civil rights and you were placed behind barbed wire with no freedom. Your life is just turned upside down.”

Kimoto remembers how embarrassed her family felt at the degradation.

“I remember my mom and dad had some very good friends that came to visit them and wanted to know if they could do anything, or help them,” recalls Kimoto. “We had to go up to the fence to see them, and it was all barbed wire. I remember my mom crying. It was pretty humiliating when you don’t have a crime that you’ve committed – the only crime is having Japanese ancestry.”

After months at the Portland Assembly Center, the Japanese were bussed over to Union Station and shuttled onto a train that took them East to Minidoka. Kanada recalls the trip vividly.

“The windows were all covered up with cardboard, so we couldn’t look out,” she says. “I just remember trying to peek out the window, and the train started and I bumped my head.”

Minidoka was one of the 10 major internment camps scattered around the United States. It was in a remote area away from everyone.

“We stop and we get off,” recalls Nakata. “I remember a man with a clipboard was there. And he said, ‘Family 15066, you are in Barrack number 6. This is Block 34.’ Our family found Barrack 6. We were in Unit A. Here I am, number 15066, and my address is 34-6-A. Aren’t I a person? I’m just…I’m just a number.”

Many remember workers building fences around the camp, which was still being constructed around the new residents. “There was nothing ready for us,” says Kanada. “We had to take some pillow cases and stuff them with straw to make mattresses for ourselves. Each family had a room, maybe 12 by 12. We had one potbelly stove that we had to feed coal into to keep it going.”

Their new homes were converted army barracks. The walls were made of thin tarpaper and had no insulation. Many families divided their sleeping section from the living section with large blankets in an attempt to simulate a home.

“I remember the inconveniences,” says Kimoto. “When you’re a child and you live under those circumstances, you don’t know anything else. You don’t think about not having to share the bathroom with 50 other people or eating in a mess hall where your mom doesn’t have to cook.”

Kanada says she feels spared by some of the miseries because she was so young at the time.

“I consider myself very lucky in a way because I didn’t have to go through everything that my parents went through,” says Kanada. “I was angry, like anybody else would be about it. It made me angry that my parents had to lose those years of their lives. They had nothing, and they had to start their lives all over again.”

In the summer, the heat was unbearable, with temperatures reaching up to 110 degrees. The dust storms were constant, with debris covering the interior of the shoddily built rooms. After every storm was over, they’d sweep the dust out through the floorboards.

During the winter, the cold and rain were relentless. All the dust turned to mud. Both Kanada and Kimoto recall walking from their evening baths back to their homes. Wooden planks had been placed on the ground as makeshift sidewalks. But they often slipped and landed knee-deep in the mud.

Not all memories from the camp were bad. Both women recall singing at Christmas celebrations, playing with the other children and receiving candy.

“I had the freedom to roam around the blocks,” says Kimoto. “I wasn’t afraid to talk to people. I was a chatterbox. I would go around and collect candy from my parent’s friends. I would come back with so much candy. So my father made a sign for me to wear and it said, ‘Please Don’t Feed Me.’”

But any laughter usually faded quickly. The atmosphere at the camp was one of deprivation and control.

“The guards were up there in the towers,” says Kanada. “We were all behind the barbed wire fences and their guns were all pointed in at us. They weren’t trying to protect us from the other people, but to keep us from running away. We really were in prison – a concentration camp.”

In the early months of 1944, Kimoto’s father received a worker’s pass, allowing him to leave Minidoka for Chicago, where he found a job as an electrician. He later became a grocery business owner again. Eventually, on July 9, 1944, the rest of the family received “indefinite” passes to join him, which meant they could have been forced to return to camp at any point.

Kanada, however, stayed in Minidoka until May 1945, a few months before Japan surrendered. They were free to return to the lives they had had prior to being interned.

Many families, though, returned with almost nothing. Each family was given a train ticket back to where they came from and a small amount of money, but not nearly enough to sustain their lives. Some, like Kanada and her family, had to live in halfway homes until they could find employment.

She recalls a time when her mother would feel along the edge of the mattresses in the halfway home with her hands, killing any insects so her three children wouldn’t get bitten while sleeping. She also remembers sitting on a bed with her family in their small room eating Wonderbread, a treat she had never had before.

During the years following the war, both Kanada and Kimoto experienced mistreatment.

As Kimoto entered into a new school year, she recalls the attention being Japanese American brought her. “I went to a rural school in Tillamook,” she recalls. “The principal had me go on stage and called attention to my ethnicity. It was humiliating. I was scared. The war years were just too fresh.”

Things got better by the time they reached Grant. Kimoto and Kanada met and became instant friends. They were just two of three Japanese students in Grant’s graduating class of 1956. They say they never felt as though they were discriminated against, save for the occasional racist comment.

At Grant, Kanada was the president of the social club Alpha Theta. Kimoto was involved in the drama department and Girls International. Both were involved in Ecco, an all-girls service club.

“Grant was really big,” recalls Kimoto. “We had a lot of school pride. We went to all the social events, and all the games.”

Outside of Grant, Kanada and Kimoto were members of Sorelle. “It was a club that united all the Japanese girls around Portland,” says Kimoto.

Both remember the constant stigma from the time they spent that at the internment camps. Japanese families rarely spoke about being incarcerated, and when they did they would refer to it simply as “camp.”

Kimoto recalls not discussing camp at all with her family until she decided to write an essay on her experiences when she was in college.

“When I did research, that’s when I felt very angry,” she remembers. “When I started reading newspaper articles, going down to the public library and interviewing my parents, that’s when I felt the anger of: ‘How could that have ever happened to us?’

“Their rights had been taken away. They were Americans. They weren’t a threat. They were just like everyone else, trying to make a life for themselves.”

After graduating from Grant in 1956, Kimoto went to the then-Multnomah College for two years. She worked as a lab receptionist, got married in 1959, and had two daughters.

Kanada graduated from Grant ranked seventh in her class. She attended Portland State University for a short time before getting married and having two sons.

Both women are widows now but still use their experiences as internment survivors to inform others.

Kimoto recalls the time she traveled to Roseburg to give a presentation to her youngest granddaughter’s class. She showed the class a board covered in photos, and a small pink and blue slipper dangling from a pushpin. Her great aunt crocheted it for her while in camp and Kimoto used to wear it around the camp because there wasn’t a way to purchase any accessories for outfits.

“When you’re young, you’re idealistic,” Kimoto says. “You have a different attitude, I guess. And then writing it much later, I wanted my granddaughter and her classmates to understand what happened.”

Kanada spoke on a panel called “Portraits of American Women,” put together by a local branch of the National Conference of Christians and Jews. The women hailed from different ethnic backgrounds and faiths, and they traveled across Portland to talk about their experiences.

“The purpose was to show that just because we look a little different on the outside doesn’t mean we’re really different,” Kanada says now. “We are still people. There’s no reason to fear us. People usually fear foreign things, unknown things.

“It’s influenced my thinking about other people. It’s made me feel different about social injustices nowadays. Like how people feel about minority races, people need to give thought, and not call prejudice because of what other people have done. It had nothing to do with them. It had to do with their ancestry. People need to be aware that diversity is good thing, not a bad thing.” ◊