When you see Dominick Branch approach, he’s not exactly a commanding presence. At 14, the Grant High School freshman is only five-feet tall. But he constantly shocks people with a seemingly endless store of energy.

A shuffle in his confident gait is the only thing that tips people off to a childhood accident that left him with no toes on his left foot. Since then, he’s done everything he can to put the image of someone with a disability behind him.

Instead, when people think of Branch, a variety of personas come to mind. Just ask his friends or his teachers.

Jokester? Only when the time is right. Jazz musician? Of course. Hardworker? Check. High school football player? Despite his injury, he added the title to his résumé in the fall.

“I couldn’t believe it when he went out for football,” says Donna Wax, the mom of one of his best friends. “And he just threw his body in there and just made it happen. I mean, this guy’s embracing it all. He wants to do it all.”

When it comes to Dominick Branch – known to his friends as “Domo” – it quickly becomes apparent you can’t put a label on the kid who plunges head first into everything.

“I just figured out that music is what I want to do. And since I’m still alive, because I could have died, I want to make it in life so I can say that the injury hit me but I bounced off of the injury faster than anything,” he says.

Branch was born in May 2000 to Juanita Thomas when she was just 16, something Thomas says “made me grow up faster.”

“I was a child having a child, so he was going everywhere with me,” she recalls.

Thomas wasn’t able to finish high school and attended Youth Employment Institute, where Branch went to daycare. He was introduced to the drums at 2 when his grandmother took him to see the movie Drumline. “After that movie, it was like, yeah, I want to go back to my grandmother’s house and beat on every can I find,” Branch says now.

When he was 7, he tried private drumming lessons, but Branch itched to get out and be active. He became involved in sports, specifically football, basketball and even a bit of soccer.

But the moment he decided to embrace all the sports, his life came to a grinding halt. At 8, Branch ventured out one day to play with his friends by the TriMet light-rail tracks. They were trying to reach out and touch the train as it rumbled by when Branch’s shoelace got caught. His left foot was dragged under the train.

“After that, it was blank until I got to the hospital,” says Branch.

He underwent emergency surgery to put pins into his toes. However, a couple weeks later, it was clear the surgery wouldn’t take and all five toes on his left foot had to be amputated.

After a month in the hospital, he was able to come home. But he feared how his life would change. As a kid, he would always stand up and dance to any song that was playing. He wondered if he would be able to continue to be active.

“I told him just because he has his disability, that shouldn’t stop you from wanting to do anything,” Thomas remembers saying. “You should still be able to do, you know, anything you want to do.”

By the end of fourth grade, he was able to play sports again.

When he recalls the accident, he realizes that he was lucky not to be more injured. He acknowledges that he’d also do things differently. “If I could go back in time, I wouldn’t have done it,” he says now. “But I’m glad that it happened because now

I can be a drummer and I can realize what my true gift is.”

On the side, Branch still found time to dabble in drumming. He had a drum set at his grandmother’s house, and though he didn’t take formal lessons, he would pass time making up his own rhythms.

Near the end of his elementary school years at George School in North Portland, Branch made a pact with two of his friends: they would all go to Beaumont Middle School. But the friends bailed. Branch soldiered on, making the trip each day that required two bus transfers from his house.

At first, Branch was unsure of the new school that was far from his home and like nothing he had ever experienced. At least until he “started falling in the love with the band,” according to Thomas.

Even so, band class didn’t come without challenges. Branch struggled with slowing down his drumming and going back to the basics. “I didn’t really know what I was doing and I was kind of annoyed because everything was just so hard,” he remembers.

He’d grown up playing music by ear. Now everything was structured.

Band teacher Cynthia Plank says the frustration is common in students who have learned through listening rather than reading music. She knew Branch had potential.

Wax recalls one particular car ride when she was taking Branch up to a band concert in Bellevue, Wash. He turned on an Ella Fitzgerald song and began to scat sing perfectly. Wax remembers asking, “Domo, how many times have you listened to that?”

It was his third time.

At Wax’s house, Branch would tinker around with any instruments that were readily available. “Somehow, it’s just natural for him,” she says.

Halfway through seventh grade, Plank believes she hit a breakthrough with Branch, who came to realize that reading rhythms would open musical doors.

It was near the end of that year that Branch was invited to play a gig with the eighth-grade jazz band, “The Ambassadors.” His stage presence is what struck Plank.

Plank set up private lessons for Branch with Chris Brown, the son of Mel Brown, a prominent jazz musician in Portland.

Along with private lessons, Branch earned a scholarship to go to the Mel Brown jazz camp at Western Oregon University.

Meanwhile, Branch’s high school plans were becoming shaky. He had always assumed he would go to Grant and continue on with his middle school friends. However, near the end of his middle school career, it looked as though Branch might have to attend Roosevelt, his neighborhood school.

A coalition of Beaumont parents, working with Branch’s family, won a hardship case for him to attend Grant. They compiled teacher recommendations, wrote an application, and met with the principal. And won.

Says family friend Wax: “People are just willing to help this kid because he gives 100 percent.”

This past August, as a freshman heading into high school, he attended the Mel Brown camp and a camp at University of Oregon. After his first camp, Branch came home for one day because it was his mom’s birthday. Then he headed off to the next one.

Through the Western Oregon camp, Branch met Laz Glickman, 14, who would eventually be the pianist for the original trio they formed (which has steadily morphed into more like a group of six).

They threw around some band names. Branch Trio was tossed out. Jones Trio.

“And it wasn’t right…We were thinking what could be a good project? And then we said, ‘Oh, the Innovation Project.’ And I was like, yeah, because we innovate,” recalls Branch.

Glickman, 14, lived in Bend, but when he moved to Portland in August, the group began to meet regularly. Since then, they’ve added a saxophonist, a trumpet player, and even a singer, whose mother, LaRhonda Steele, is a prominent jazz singer in Portland.

As a freshman at Grant, Branch quickly transitioned. He joined Black Student Union as one of the freshman representatives. A couple of weeks before school started, Branch joined the freshman football team.

Coach Karl Acker recalls Branch walking directly up to him, saying that he was going to join the football team.

“Who would have known that he would be a spark plug for us,” says Acker, who admits he originally thought Branch would be a jokester, a kid who is all talk and no work. But, he realized Branch focused his energy on bettering the team.

Acker says such commitment was especially inspirational, given Branch’s situation: “Nowadays, we have so many athletes that come up with excuses for reasons why they don’t want to practice or excuses for why they don’t go a hundred percent in practice.

“Here’s a guy that has trouble just walking and running, doing the things that we normally take for granted, and here he is every day out there trying to get it in.”

Germain Jordan – Branch’s stepdad – plays professional basketball in Sweden and says even at a high-level, players make excuses with little reason.

Assistant football coach Alex Melson, who was Branch’s primary coach, refers to him as the “pep guy” for the team because his voice could be heard roaring over everyone else’s on the field or from the bench.

His energy is evident to everyone – whether he’s creating a beat or dancing around on the field during practice, according to Melson. Once, he got up and did the entire Michael Jackson “Thriller” dance in Dan Anderson’s history class.

Grant band teacher Brian McFadden says sometimes he’ll put Branch’s music on over the loudspeaker and the class will start playing along. Branch sits at the drums, a baritone saxophone joins, and soon everyone is in on the fun.

“He just brings in a really interesting, positive personality, and a musical personality that makes people want to start playing with him, which I think is a pretty unique thing,” says McFadden.

McFadden says what sets Branch apart is how students appear to get pushed by him. “He’s doing that through his playing and not necessarily all the time through what he has to say, but when he does have something to say it’s always a wisdom beyond his years,” the band teacher says.

Jeff Jones, Wax’s husband, remembers when the band performed at an assisted living facility. While the other kids wavered at the periphery, unsure of how to approach older, less healthy people, Branch didn’t hesitate. Clasping an old man’s hand, he offered a “And how are you tonight, sir?” The man was shocked.

Branch dreams of going to a jazz school in New York City, and he’s doing everything he can to get there.

McFadden helps facilitate jazz lessons with a Bend teacher over Skype who noticed Branch at a gig Project Innovation did in Central Oregon. Noticing Branch’s potential, he worked with Jones’ family and other band members to give Branch free lessons. Private lessons, after all, will take Branch to the next level.

It’s not all about the music. He says grades are important to him because they open doors.

Mary Rodeback, Branch’s English teacher, says she often finds him camped outside of her classroom at 7:30 a.m. or during lunch to ask a question.

Recently, when the class went to go pick out books for a literature circle, Branch asked for a book that would challenge him. “There are few students in my history as a teacher who work as hard as Domo does,” she says.

With Thomas working toward her business license to cut and style hair, she has to attend school from 5 p.m. to 11 p.m. during the week. With Jordan in Sweden, Branch has to be resourceful with his time.

Wax remembers how Branch came to eighth-grade parent’s night to give information about the band program, even when he wasn’t the drummer playing one of the pieces.

“That’s how he is. He signs up for something. He puts one-hundred percent in,” says Wax.

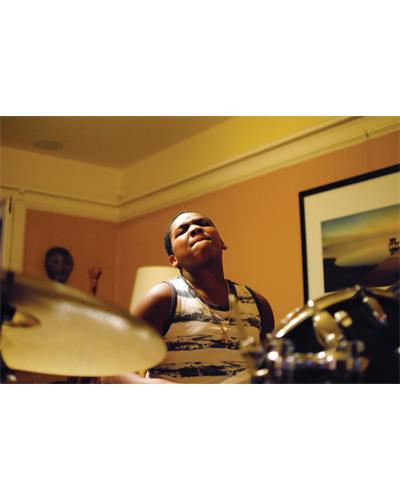

At a recent band practice, Branch is in his element, seated behind an array of drums and cymbals. He’s all jokes until the music starts going.

His eyes close and he lets the beat carry him. All members have their eyes keenly focused on each other; one person goes out on a limb, taking a solo, and there’s a moment of tension before the group comes together once again and Branch gives a reassuring nod.

It’s a different Sunday night than most kids who are cramming in last moments of homework. For two hours, it’s all music for Branch.

Every once in a while, the band members trade new songs they’ve listened to and enjoyed.

Says Branch of the band: “I see this band going very far. In the future, yes, I think there will be no more Innovation Project. But, I think that there will be Innovation Project parts.”

Thomas smiles when she thinks about how far her son has come since the accident and what he’s doing now.

“Jazz in the shower. Jazz when we wake up. Jazz when he walk in the house. It’s just music, music, music,” she says. “You know when Dominick is coming.” ◊