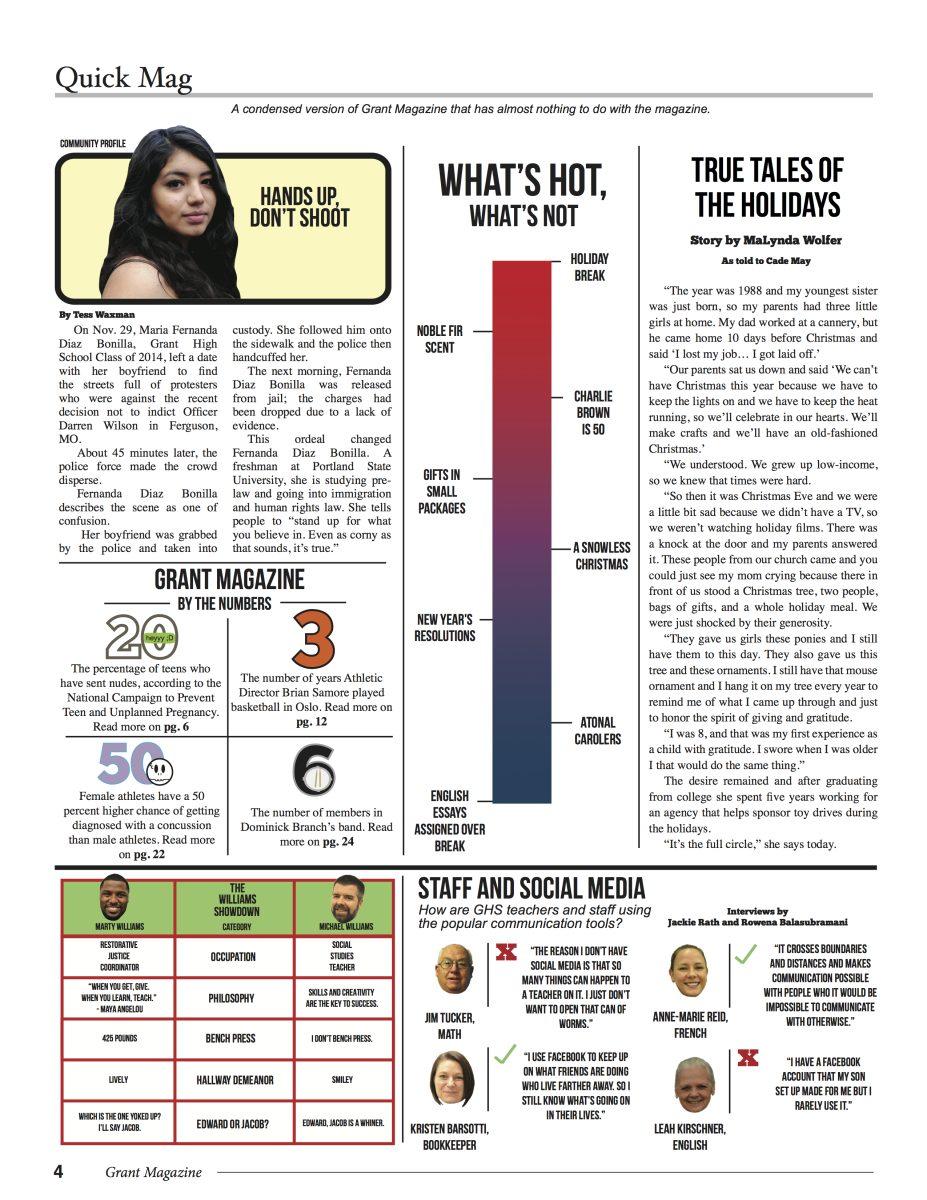

It’s a Saturday in August and Brian Samore walks through Grant High School’s Center Hall, covered in dirt. He’s a few weeks into his new job as athletic director and dean of students, and his cheeks are flushed and his hair ruffled.

Samore showed up early to help trim hedges, cut the lawn, pick up garbage and shovel bark dust at a community cleanup of the school grounds. In between tasks, he chats with students, their parents and other Grant staffers, seeming more like an old fixture than someone who is new to the school.

A few weeks later in the middle of a school day, the 6-foot-5-inch Samore ambles through the main hallway to the Athletic Office. He pats a back, shakes someone else’s hand and offers encouragement to several other students – pleased because he’s got almost all of their the names down.

And when the Grant boy’s soccer team made it to the state championship, it was Samore who gave an impassioned plea on the bus before the game. He urged the players not to define themselves by the final score. Above everything, he told them, make sure you leave it all on the field.

In his first few months on the job, it’s clear that Samore, 54, is more than an administrator who simply does his job by the book. He’s come a long way from his upbringing near the cornfields of Iowa, a life driven by equal parts curiosity and wanderlust. Rules, he says, mean nothing without the relationships. So when the loud, pumped-up voice, clapping hands and excited grin don’t give it away, the connections Samore is forging at Grant make a few things clear: This is where he belongs and he’s eager to connect with everyone at the school.

“One of the things that stood out was his ability to generate relationships, both with adults and students,” Principal Carol Campbell says. “He’s been a teacher. He’s been an administrator. He’s been an athlete. He’s been a coach. So he’s able to call on all of those experiences and pull them together.”

Samore compares the job to the arc he’s traveled. “This job is kind of a culmination of my life in a lot of ways,” he says. “I have a real strong sense of where the athletic program should be going and the things that we need to do to get there.”

His energy – and the attitude of not waiting around for others to make things happen – is contagious. Nick Branch, one of Grant’s custodian, says he admires Samore’s work ethic and remembers the first time he saw him.

“I see that guy. He’s in the ditches, man,” Branch says. “He’s moving. He’s picking up garbage. He’s taking tickets. He’s sweeping up the locker room for the kids. He’s getting them water. I was like: ‘Wow, this man, yeah – he’s in slacks and he’s outworking me.’ I think he’s gonna fit just well.”

Born in Sioux City, Iowa, to a first-generation Lebanese immigrant father and an Irish-Welsh mother, Samore was the youngest of five brothers. The older boys – John, Ted, Richard and David – showed no mercy in making their physical superiority over their little brother well known. “When his ego started to get out of line, we did what big brothers do,” recalls David Samore, now 59.

The youngest Samore was no match for the four pairs of hands that introduced him face first to – as he recalls it now – “toilet twirly time.”

But it wasn’t always fun and games. The values of being well versed, growing from discourse and understanding conflict resolution were all instilled in Samore and his brothers early on. Every night, the boys and their parents gathered around the kitchen table to eat dinner. “It was always very, very animated,” remembers Samore.

Some nights, his mother would grab a dictionary and encourage her sons to learn the difference between words like egocentric, egoistic and egotistical.

Other nights, the discussions centered on civil rights or political candidates. Things got heated, Samore recalls, but it nurtured his ability to think for himself.

They interrupted each other. Silverware was thrown. Plates of boiled vegetables crashed against the yellow, metal table frame. Chairs were knocked over.

Yet, “we weren’t allowed to hold grudges,” he says. “We basically just had to hug it out. My parents instilled and cultivated within us that discourse and debate is good. That’s why I gravitate toward conflict. We become stronger, our relationships become deeper because we wrestle with each other.”

His dad hosted monthly rap sessions – inviting friends, neighbors and others into the living room for impromptu debates. Should we be in Vietnam? Nixon vs. McGovern? What makes “good” music?

“We recognized that our friends didn’t go home to ones like ours,” David Samore says now. “It was kind of a menagerie.”

Samore recalls the same memories. “I remember the verbal crossfire back and forth and just being amazed,” he says. “Intimidated a little bit, but amazed at what was being said.”

The debates planted a seed in Samore, pushing him to want to see the world outside of Iowa. When the last of his brothers left the house in 1971, Samore became the centerpiece.

“All of a sudden the house went silent,” he remembers, as reading Shakespeare replaced the raging dinner discussions. He developed a deep love for poetry that he later pursued in college. “The stage opened up and I took off,” he says.

Throughout high school, Samore excelled in athletics – especially football and basketball. “Brian was every bit the big man on campus,” says David Samore. “He wore the letterman jacket, had swag, girls chasing after him. I think he pretty much thought he ran the place.”

Diane Shanafelt, a close childhood friend, says his spirit often made him “a handful in the classroom.”

“There was always a show when Brian entered,” she says. “You knew something was going to happen. He was gonna be the one to speak out. He was gonna be the one to do something when the teacher wasn’t looking.”

But his popularity didn’t overshadow his unflinching desire to be present for others. “Watching my parents handle us had a direct effect on how I interact with everybody, from the mayor to the custodians,” says Samore.

They taught him the “critical importance of being able to listen and respond to other people’s concerns or points of view; not just listening and waiting to talk,” he says.

Shanafelt says the quality took Samore far. “Cultivating relationships is extremely important to him,” she says.

As soon as he graduated, Samore left Sioux City without looking back. At 19, he stood on the side of the road holding a cardboard “San Francisco” sign toward the blur of oncoming traffic. “For me, it was a way of traveling cheaply. But more importantly, it was a way of being thrown into a life situation with people,” he says. “I loved standing on the side of a road and suddenly, within seconds, I was catapulted into a car full of college partiers or an old couple.”

He attended Grinnell College, a small liberal arts school in Iowa. He played basketball, delved deep into the arts and had a radio show called “The Real World.” But after two years, his wanderlust kicked in. “I didn’t want to waste anybody’s time and money,” says Samore. “I was taught to value education too much to be so cavalier with it. I was being cavalier with my education. And I didn’t like that.”

He sold his turquoise blue 1964 Ford Falcon, making just enough for a one-way ticket to Europe where he planned to pursue playing professional basketball. He eventually landed on a team in Oslo, Norway, where he played for three years. “I really kind of grew up there,” he says.

When he had down time from basketball, he created a youth program and also worked in an auto body shop to earn extra cash. “It taught me the value of blue-collar labor,” says Samore. “I was working with these guys who were toothless and funny looking, and they just were really good salt-of-the-earth people who took me under their wing.”

Working alongside the locals taught Samore to treat everyone with the same level of respect. “If you’re walking with the mayor or if you’re walking with the ditch digger, you’re walking with the same demeanor,” he says.

One day, while working out at a gym, Samore was approached by Russ Conn, who asked him to borrow some money for a soda. “He caught me being an American trying to speak Norwegian,” says Conn, who had just moved to Oslo from San Francisco. “From that moment on, we were very close friends.”

Samore’s hunger for adventure and pushing limits rubbed off on Conn. “There’s very little down time for Mr. Samore,” Conn says. “He’s one that pushes the clock. And he pushed me.”

One night, the pair found themselves alone on a ski slope. Everyone had left and the lights had been shut off. Samore remembers the moonlight casting a dusky haze over the mountain. As they traversed down, cheeks red from the chill, they tried knocking each other down – anything to enhance the thrill.

At the time, Samore was prone to homesickness. He’d barely had contact with his family. He thought back to what his mother had taught him about the value of “roots and wings.” He realized that he’d had enough self-discovery for the time being. “I had set up this whole other world that nobody really knew,” he says now. “One day I just said ‘What the hell am I doing? I need to get back and get on with my life, finish my degree.’”

He moved to San Francisco, got a job at Powell’s Books in Union Square and attended the University of California-Berkeley. “I was free, I was confident, I was making money and going to school,” he says. “I was driving a motorcycle. I was growing up and still being a kid but doing the right thing for my future.”

After earning a degree in psychology, Samore realized he wanted to explore Southeast Asia. “I wanted to get further and further away from the American machine,” he says. “And Southeast Asia was the best place to do it.”

He flew alone and traveled through Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, Malaysia and Indonesia. His livelihood was built on 47-mile treks alone across islands. Kids ran up to him to touch the hair on his arms then ran away. “People thought I was something out of some kind of biblical book,” he says.

He visited Mount Rinjani, the second highest volcano in Indonesia. Samore had heard there were a number of remote Indonesian people living near the volcano’s base. So only capable of communicating two words in the native language – beer and bathroom – he stayed with the Sasak people. He slept beside a crater lake inside a part of the volcano and learned to fish for carp, using only a pebble, a thin line and his finger. He ate fish eggs off banana leaves and watched the clouds swirl above like watercolor paintings.

“What I remember thinking is: ‘I’m in the middle of nowhere and so many things could go wrong. And yet, again, so many things have gone right,’” he says. “It was a crystal manifestation that people are good. That’s why we travel.”

Ten months later, Samore was back in the states, this time in New York City. “That was where I had to go,” he says.

He entered Columbia University’s graduate program and got a job working at Manhattan Center for Science and Math in East Harlem. Working with underprivileged kids was a whole different ballgame.

“It was one of those things where the cuts were so deep,” Samore recalls. “Most kids – if they trust you and respect you, and you’ve earned that – respond to a kick in the pants. But a lot of these kids had been kicked in the face so many times they didn’t even feel a kick in the pants.”

But Samore didn’t give up. “When you’re at the most dangerous part of the climb and things start to get crazy, I kinda get in my comfort zone,” he says.

He had a number of roles at the school that allowed him to bond with the students and forge relationships. He was a math teacher, drug and alcohol counselor, mediator, college counselor and coach.

He also met a woman. It was 1990. Samore was at a Christmas party at the Dakota, one of New York’s oldest hotels. “She was the only one not dressed in black,” remembers Samore. “I was the only one not dressed in a suit and tie.”

He describes it as true love at first sight. Heidi Storm was telling a story in the middle of the room and whistled like she was calling a cab. All eyes turned to her, Samore’s a bit larger than the rest.

She recalls the evening clearly and her introduction to Samore. “After I whistled, he got down on his knees and said ‘Will you marry me?’ And I thought: ‘Gosh. He’s smooth,’” she says now.

Two weeks later, they started dating. “After three dates, I knew that I had found my wife,” Samore says.

They fell into the New York lifestyle – meeting in Central Park, going on dates late into the night and working – Heidi as the director of marketing for Hilton International and Samore as head coach for a basketball team in East Harlem.

But they decided to leave it behind after a while. They packed up a U-Haul and wound their way to Portland. “We came out here with no job, no family, no home, no anything. We just said, ‘This is where we want to go,’” says Samore. “Then we said ‘Let’s do this husband and wife thing.’”

After eloping to Thailand, the two returned to Portland to settle into a small apartment in Northwest Portland.

Soon after, Heidi was pregnant.

Sierra Samore was born in November 1995, the first girl born into the Samore family in 65 years. By then, Brian Samore had his first job in Portland as the student management specialist at Fernwood Middle School. In 1998, he became Dean of Students at Jefferson High School.

Tearale Triplett, now a Grant counselor, worked alongside Samore at Jefferson. He remembers Samore sauntering down the halls with a red “Carpe Diem” stamp in hand, greeting each student and staff member by name and a clap on the back.

At the time, Jefferson had recently been reconstituted and “we needed to have that energy to lift the school, emotionally,” says Triplett. “He’s in your face. ‘How you doing?’ and it’s like seven o’clock in the morning. When everyone else is dragging, he’s bouncing around.

“He just put a human face even on discipline. I think his humor and his gregariousness allowed him to bridge the gap between kids and parents of all ethnicities and races.”

Russ Peterson, who teaches English at Grant, also worked at Jefferson alongside Triplett and Samore. He remembers struggling as a new teacher and being sought out by Samore.

“Mr. Samore really gave me the graduate education that I needed,” says Peterson. “He kinda took me under his wing and broke it down: ‘These are some strategies you can use, and if you want, I can sit in back and be a presence in the classroom if you need it.’”

Peterson describes Samore’s approach as “holistic.”

“He was – and still is – really big on building a relationship with the students,” says Peterson. “I mean, not just knowing their names, but going to their games. Talking to them in the hall. Just things that put you in a position where you’re not being a hammer but rather coming at the students from a place of respect and understanding. And I think that’s just really good advice.”

While his work was going well at the time, Samore’s family life took a turn in 2002. His brother, Richard, was diagnosed with bronchiolitis obliterans, a rare, life-threatening lung disease.

“If you’re on top of Mount Everest, they say that you’re at 15 percent oxygen,” Samore says. “My brother was living every day on 10 or 11 percent. Even combing his hair was exhausting.”

He went back to Iowa to shut down his parents’ home of 54 years. He brought his mother and brother to Portland. Richard slowly deteriorated for 13 months. “He was holding on because I think he was afraid of dying,” Samore recalls. “He didn’t want to leave the party. I would feel the same way.”

The death of his brother reminded him of the basic family values that he learned around the dinner table. Today, he fosters those same values within his own children, working to create balance between work, school, adventure and family time.

His children know that participation in family time isn’t up for debate. “When we’re together as a family or we’re with other people, he expects us to be present,” says Sierra Samore.

Her brother, Kelton, 15, puts a little more emphasis on the rules. “Do not even think about whipping out your phone while we’re having dinner,” he says.

At school, the walls of Brian Samore’s athletic director office are lined with 16-by-20-inch prints of his world travels. As two students work in tandem to put up a new blue and gray bulletin board, Samore claps his hands and spins in his chair as another lively tune comes on the radio.

He asks one of the students to turn up the volume. As the beat pulses, Samore throws down a challenge: “I will buy anybody in this room a drink of their choice if they can tell me who sings this song.”

Aretha Franklin? “No,” he bellows. “No, not Aretha. Anybody? Anybody? It’s the Staple Singers. Come on now.”

Samore leans back in his chair and smiles with his eyes closed as he sings – hands in the air – “I’ll take you there, Oooooooh!”

His computer screen and keyboard have more than 10 yellow sticky notes – the makings of the day’s to-do list. He rubs his hands together and gets back to work, thinking about where he is and his role at Grant for a moment.

“This is exactly where I’m supposed to be right now in my career,” he says. “I get a chance to be an administrator, but I still get to be connected with kids. I’m involved in sports and I’m right down the street from where I live. This is a dream job for me.”

In the meantime, he’s focusing on his goals – learning every Grant athlete’s name, sport and specialty, as well as pinpointing what he can do to help them stay on top of academics. He’s adept at setting up athletic team schedules and making sure every home event runs smoothly. And very few people in the building work as hard as he does.

On a recent weeknight, it’s well after the school has closed. Samore hangs up the last phone call of the day, tears a few of the sticky notes off his computer and heads for home. After a lively discussion at the dinner table, the chatter is replaced by Spanish music.

He leans back and soaks in the time he gets to spend with his family, even though plans for the next day at work are brewing in his mind. “I’m humbled by the world’s generosity to me,” he says. “And therefore, I need to give the world everything I’ve got back.” ◊