At 5-foot-11 inches tall, Rebecca France has always been accustomed to the physicality that comes with playing high school basketball. The elbows, the shoving and the jockeying for position on the court are all part of the game.

So it didn’t come as a surprise to France last spring when an opponent’s hand hit her above the mouth as she went up to take a shot. Even though she had a bright red imprint of a hand on her face, France stayed in the game.

Later, the shaky feeling she got from the blow turned into a severe headache. Doctors told her to take time away from sports because she had a concussion. “I basically just sat in a dark room, not reading or watching any TV,” says France, who is now a sophomore at Grant High School. “Kind of the only thing I did was sleep. I was really sensitive to lights and noise.”

More than eight months later, France, 16, is still plagued by headaches and other problems as she works to get the OK to return to the court. Experts say what happened to her is all too common among female athletes.

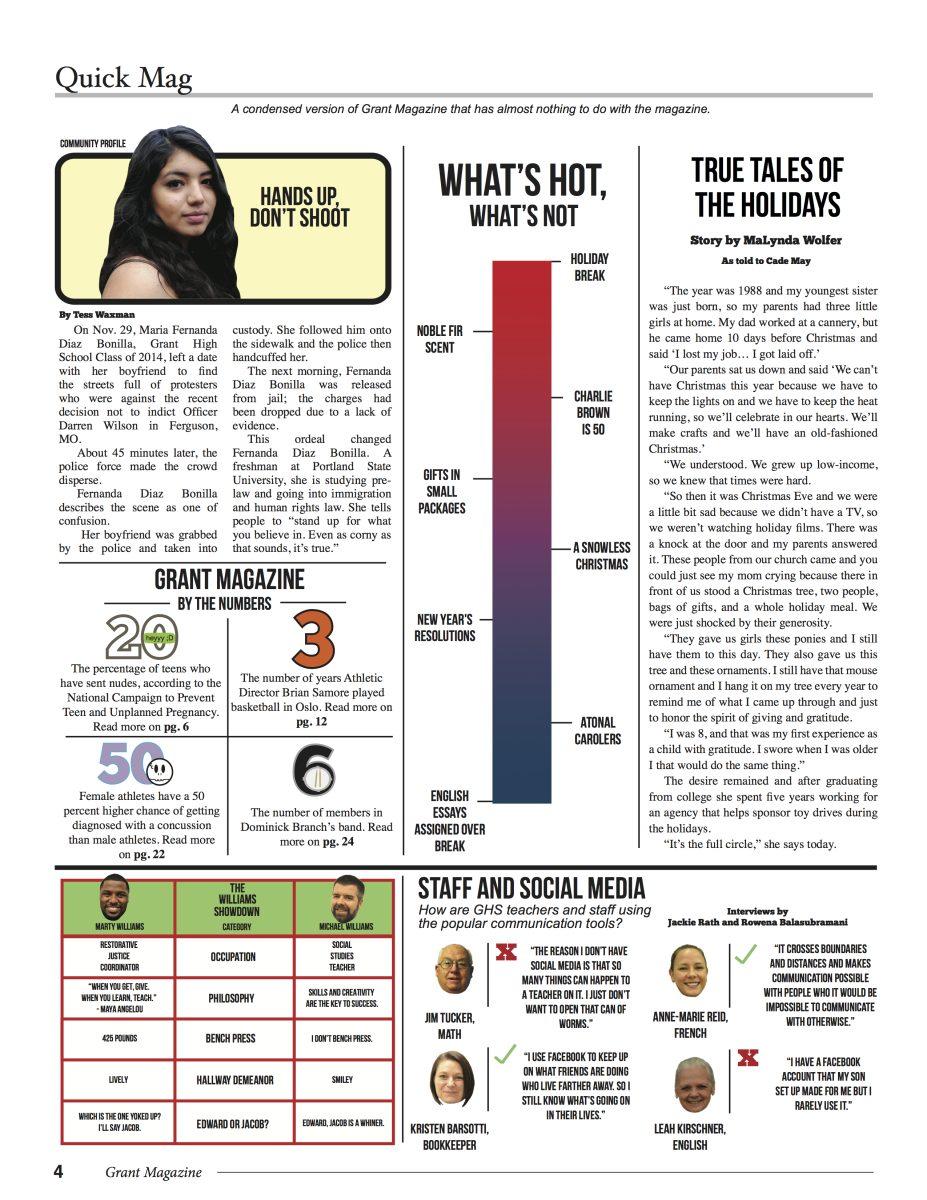

Concussions happen when the brain rocks violently within the skull, either caused by a blow to the head or a sharp jerk by the body. Studies have shown that in sports played by both genders, girls typically get diagnosed with head injuries at a higher rate than boys.

Dr. James Chesnutt, who specializes in pediatric and adult sports medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, says the reasons aren’t set in stone. But some theorize that the differences between body types might have something to do with it.

“I think some of the leading theories are that neck muscles in females are relatively weaker than males in general,” Chesnutt says, adding that reaction time might also play a role.

Alicia Sufrinko, a neuropsychology fellow at the University of Pittsburgh’s Sports Medicine Concussion Program, agrees.

“When guys have force, they brace a little bit better so they don’t have as much momentum to absorb,” she says. “Girls don’t have as much muscle. If a girl gets hit backward, her neck may snap back further than a guy’s and that transfers more force to the brain.”

Sufrinko says research shows hormones and the menstrual cycle can also have an effect. “Basically, girls have a different risk level depending on what part of their cycle they are in,” she says. “They could get hit in the head with the same amount of force at differing times in their cycle and they could potentially have an injury or concussion one time and not have it another time.”

Both Chesnutt and Sufrinko agree that societal pressures might also have something to do with the higher rate of reported concussions among girls. Chesnutt calls it a “reporting bias.”

Traditionally, society has put an emphasis on protecting girls from physical injuries. This mentality, both Sufrinko and Chesnutt say, may lead parents and female athletes to report head injuries more often.

At the same time, boys are often expected to play through injuries. “It’s the more macho thing to go out there and hurt themselves and not complain about it,” says Chesnutt.

Sufrinko says parents will push their kids. “A lot of times you have a father who has played that sport in the past and says, ‘Oh, I had a ton of those injuries. It’s no big deal. He’s fine. He can play,’” she says.

Grant’s new athletic director Brian Samore says administrators are trained now to watch out for even the slightest chance of a head injury. And that’s something that mirrors what’s happening in college and professional sports.

“We’ve been taught, the athletic directors and coaches, that anything that even sniffs of a concussion, you’ve got to treat seriously,” Samore says.

Coaches at Grant are required to take an annual hour-long, online class regarding concussions. But Samore says there’s little to no education provided for students. He thinks it’s incumbent upon coaches and players to make sure athletes understand.

“Give them the out that if they get hit, no big deal. It’s part of it,” Samore says. “There’s no more sucking it up or toughing up. Take a break. We’ve got to preserve in the long run.”

Melody Hansen, France’s mother, has followed her daughter’s sports for years and sees competition as an important part of life for many kids. She says she doesn’t think the reporting bias plays as much of a role when you look at higher levels of sports.

“I think that once it gets to a certain point, you just have to be honest,” France says. “Once it gets bad enough, everybody will report it.”

For France, the experience has been daunting. Once the game where she was hit in the face was over, she thought nothing of it. She went to school and only took one day off from physical activity. One week later, though, the sharp pain returned and her parents took her to the emergency room, where doctors told her to take a complete break from sports and school.

She worked with doctors over the summer and at the beginning of this school year to get a handle on things. Soon, she was only experiencing occasional headaches after school.

That was until mid-October. She was sitting in math class when “out of nowhere the room just started to spin,” she recalls.

“I didn’t move my head. I didn’t stand up. It just started spinning. That spinning sensation didn’t really go away for the rest of the day.”

She rested a lot and took things easy for a while. She sees a physical therapist, Nicholas Thompson, in order to get back in shape, but is careful not to push herself too hard.

Thompson says he always tries to make sure his clients pace themselves. “Many athletes who sustain concussions become frustrated and often times depressed on their lack of ability to participate in any sort of activity post concussion,” he says. “They are not used to being this sedentary.”

Over the past few weeks, France has trained with Thompson in vestibular therapy – designed to improve movement and balance for people who have suffered from head injuries. She has moved up to light physical activity.

France visits the Grant gym once a week to see the team and waits for her turn to play. “The hardest part is probably not knowing what caused it and a lot of the doctors I go to feel like I’m trying to speed up the recovery to get back to basketball,” France says. “It would be nice to speed up the recovery, but what I really want to know is why it’s all happened so I can try to avoid it from happening again.”

Her mother sees how much her daughter wants to get back on the court. And it pains her to watch the reaction at the gym.

“She looks perfectly like herself and every time she walks in the gym, girls are saying, ‘Are you here to play? Are you going to play?’” Hansen says. “It’s not like she’s got a big cast on.”

As the basketball season kicks into gear, Grant girls’ basketball coach Michael Bontemps says he misses France.

“She is someone I am counting on because she has height, which is a premium asset in basketball,” says Bontemps, who wants to see France make it back before the season is over. “She loves the game and is constantly working to improve her individual skills. We are missing her.” ◊