Ali Al Moussawi and his family pack into the car in his home country of Lebanon. They’re headed into Beirut so Al Moussawi can take the third of five exams required for him to participate in an exchange program that will allow him to come to America.

Each test is crucial for the exchange program that will choose 30 Lebanese students to partake in the completely cost-free exchange.

His hopes are high and his father is ecstatic as they make the two-hour drive from his hometown, Nabi Chit, to the capital city. As they get near Beirut, the radio interrupts the family conversation.

A car bomb exploded, killing seven people near the hotel where the family was going to stay. Kazem Al Moussawi, Ali’s dad, turns the car around and they head home.

Ali Al Moussawi remembers the helpless feeling that overtook him. “I was just so shocked and worried that I’d miss the exam,” he recalls.

Under the circumstances, the exchange program’s administrators allowed him to reschedule. After two months of studying and lengthy interviews, he earned a spot among the 30 students. With the decision came a trip to Oregon and Grant High School.

It’s been a stretch for the 16-year-old Al Moussawi, now a junior at Grant. “The first two days were too hard,” he says. “My communication with others wasn’t so good. I was nervous because coming to a new school, you know nobody.”

Clearly, he’s had to overcome his share of obstacles to get to the place that he hopes holds his future. He is excited to take advantage of the opportunity. And with a caring and supportive host family, he’s well on his way.

However, his time in America has not been just a wonderland. Al Moussawi still faces the struggles of cultural adjustment and often worries about his family back home. Lebanon has been targeted by the terrorist group Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. Known as ISIS, the group has made international news this year by capturing hostages and beheading them.

Al Moussawi, who lives at home with his parents and younger sister, has reason to worry. He lives in a small village of about 3,000 about 50 miles from the Syrian border. Israel lies to the east. His village is nestled in the Bekaa Valley.

Lebanon’s population has increased rapidly as Syrian refugees seek safer places to live. They’ve been driven out of their homeland because of ISIS advances.

Today, Al Moussawi’s country remains unstable politically and economically, a contributing factor to his plan to move to America after high school.

He first remembers hearing about bombings when he was 6. They didn’t happen in his village. But since Lebanon is only one-tenth the size of Oregon, everything feels close. “It does become normal,” he says.

His father says it’s part of the history. “This country has been living with terrorism as a routine,” he said in a telephone interview. “We’ve got to keep living despite violence and destruction. That’s the way that all Lebanese…live.”

His father works as an English teacher at multiple high schools and middle schools around their village. Other than his son, he is the only English speaker in the family.

Schedules for the schooling system in Lebanon are intense and more rigorous than in America. To move on to the next grade, students must pass a single test. If you don’t pass, there is only one retake opportunity. A similar test is given senior year to graduate from high school.

Al Moussawi says he relieved his academic stress by visiting a mountain that sits about 10 minutes from their home. It was a place he visited regularly with his dad.

He remembers a time when he was 9. He was with his father and he was feeling brave when they reached the mountain. Al Moussawi scaled a big rock that lies in between two ridges.

“That day really stuck out to me,” he says. “I got to the top and I could see everything… it was so amazing, there were no people.”

Al Moussawi’s father also dreamed of coming to the United States. When Kazem Al Moussawi’s father was a child, he became fascinated by America through watching cowboy movies. His favorite is 3:10 to Yuma. Later, he studied English and indulged himself with literature and U.S. history.

He knows his son’s journey is going to be a good experience. “Ali going to the U.S. was a hit of luck and a reward to my real love to this country,” he says.

Ali Al Moussawi remembers hearing stories from his uncle, Hamzi Al Moussawi, who had moved to Los Angeles before he was born. His curiosity grew each time he heard a story about the U.S.

Al Moussawi met his uncle for the first time in 2009 when Hamzi Al Moussawi visited Lebanon. He was able to hear all that he wanted about the United States. His uncle gave him his first cellphone and laptop, things he keeps in his room today even though they don’t work anymore. “We became very close,” Al Moussawi says of his uncle.

His uncle called every week and would tell Al Moussawi and his sister about America, where he worked as a wholesaler of auto parts.

Last year, though, the family experienced a personal tragedy. His uncle passed away in November 2013. “I was on my way home from school and the busman told me, ‘Your uncle has passed away,’” he recalls.

His uncle had lung cancer but Ali Al Moussawi never knew how severe his condition was until late into his illness. “He didn’t want to make his family worry or cry over him,” says Al Moussawi.

Al Moussawi’s father flew to Los Angeles two weeks later to bring his brother back to hold a funeral.

Meanwhile, another uncle, Khalid Al Moussawi, helped nurture a love for cars and mechanics in Ali Moussawi. “I’d always watch him and try and figure out what he was doing,” says Al Moussawi. “I just love cars. I know almost everything there is to know about them.”

Al Moussawi and his father spend a lot of time working on their Peugeot back home. He remembers taking apart portions of the engine to learn how it worked.

When not studying up on the newest sports car or hiking with his father, Al Moussawi could also be found at the local nightclub in his village. Different than clubs in America, Lebanese clubs are not entirely centered around alcohol and partying.

The school system is also different. While the length of the high school day is about the same, there are no passing periods. Students stay in the same classroom and the teachers come to them. “I like the schooling much better here,” says Al Moussawi. “It’s much nicer getting to leave your classroom.”

Last June, his teacher recommended the Youth Exchange and Study program to his class and after short consideration, Al Moussawi and his family decided it was worth giving it a shot.

The program is a non-profit organization that was formed after the events of September 11. It is a scholarship program that accepts only a select few individuals from Middle Eastern countries and is completely cost free to all who get accepted.

Its purpose is to promote peace amongst the United States and the Muslim world, encompassing almost every country in the Middle East. Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria were excluded after conflicts began in each country.

Over the summer, he had to take different exams and interviews that led to more exams and interviews, all part of the process for getting selected to the nine-month exchange. His acceptance letter came in July and a month later he left for Portland.

He had to attend a three-day cultural orientation in Washington, D.C. Al Moussawi arrived understanding little English. The language barrier was especially difficult during school.

Other aspects of American life took some adjusting to as well. He remembers being scared out of his mind by the two dogs his host family keeps. “I’m not used to dogs,” he says.

He lives with a family of four, Jillian and Ryan Carson, and their two children, Jack, 6, and Deven, 3. The Carsons own and operate Treehouse, a business that works to teach average people how to create iPhone apps.

His host family welcomed him with open arms. “We chose Ali because it seemed like he had strong family bonds,” says Jillian Carson. “It’s important because if you come here and don’t like spending time with the family, you’re gonna have a rough time.”

The Carsons have taken him on multiple outings around the city and on a trip up to Seattle. While biking around the city most weekends, Al Moussawi’s discovered other places on his own. Lloyd Center has taken up many of his days. A recent trip to Seattle and a visit to Five Guys Burgers and Fries have left him with that establishment as his favorite restaurant.

With the language and cultural barriers to fight through, adjusting has been difficult. But he’s “loved everything about it.” His home is everything he imagined. “I pictured a big house and a big car,” he says, “and got just that.”

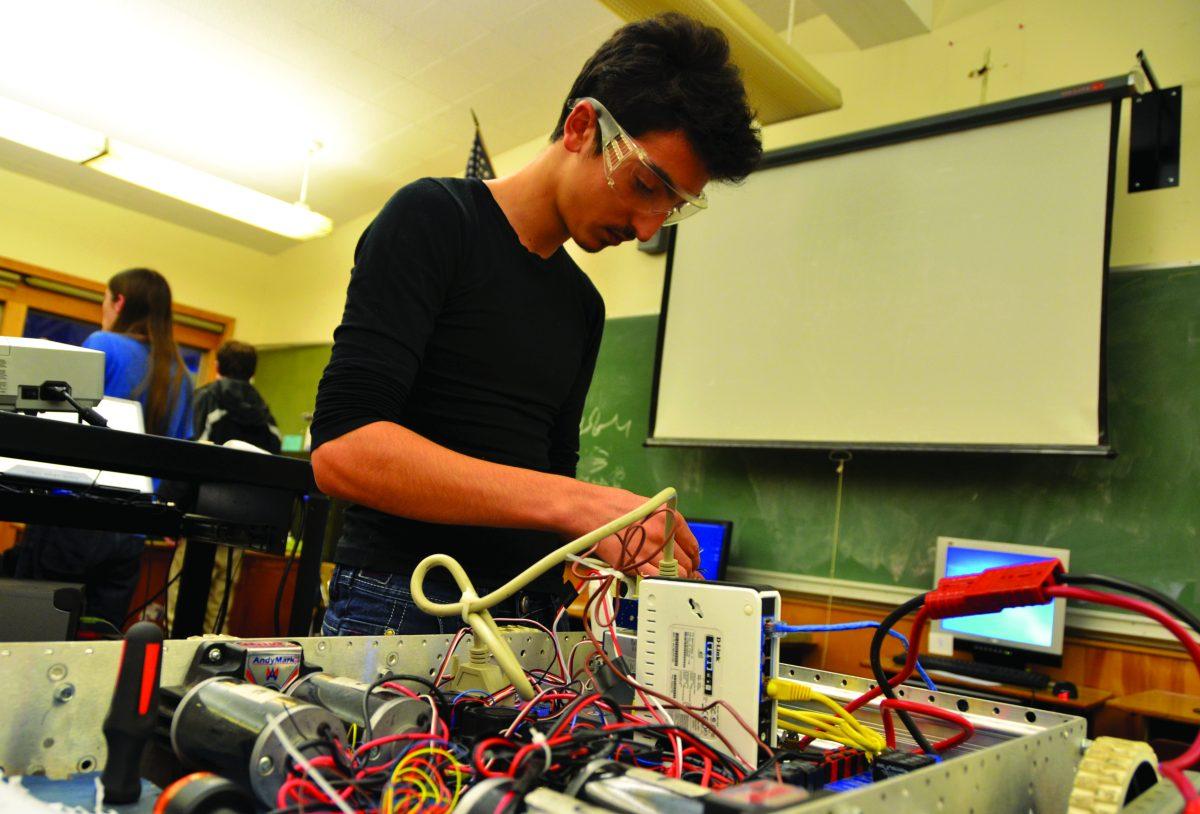

At Grant, he joined the Robotics Club because it’s the closest thing to being able to use his skills on cars. On his first day in class, senior David Newcomer gave Al Moussawi and his partner Daniel Bivens a challenge.

“I unwired the entire machine and asked Ali and his partner to rewire it and he did it really well,” says Newcomer, one of the club’s co-captains. “He’s doing some really tricky stuff.”

While Al Moussawi likes to keep himself busy, he’s constantly thinking of family back at home. He misses the time he spent with his dad.

“We were like companions. We went together for everything,” he says, acknowledging that he also can’t go two days without talking to his mother. “I actually call my mom more than my dad. I miss her so much.”

A series of attacks by ISIS have made him fearful for his family. The village of Brital, which is only 20 minutes from his village, was attacked in late September and threats from ISIS leaders claim that more attacks to the Bekaa Valley are imminent. Officials say more than a dozen Syrian-based militants were killed in the attacks along with other extremist fighters. “We do feel unsafe over here,” his father says. “But the Lebanese army is taking security precautions.”

Ali Al Moussawi says he’s still concerned. “My parents don’t want me to worry about them,” he says. “But I am worried.”

Looking ahead, Al Moussawi has plenty to do with his remaining time here. As part of the exchange, students are taken on monthly immersions, such as tours of the city or trips to the coast. Soon, the exchange group will meet for a holiday party where each student can share regional cuisine with everyone in the program.

Exchange students will experience so much immersion during their trip in America that “they’ll have a culture shock when they get back,” says Dorris Robertson, the head of Al Moussawi’s immersion group.

Al Moussawi will return to Lebanon a couple weeks after the end of school in July 2015. He will have to partake in a cultural immersion orientation in Washington D.C. again. The conference is structured to help exchange students smoothly adjust back into their home countries.

“They’re thinking in English,” Dorris Robertson, who works with the exchange program, says. “They can’t say things they can say here. It kicks when they get back but they adjust.”

Once Al Moussawi returns to his home country, he plans to finish his senior year in Lebanon and then head back to the West Coast in the U.S. for college. He hopes to major in mechanics and open a shop of his own. Although he enjoys Portland, he wants to move to L.A. so he can be just like his uncle.

“I want to see the life that he was living,” Al Moussawi says. “Other than my family and my car, I won’t miss anything. It’s not because I don’t like Lebanon. But since I was nine years old, when my uncle came for the last time, since then I’ve been determined to come to America.” ◊